It still comes as a surprise for many lawyers and judges to learn that there were thoughtful people who bore serious doubts, at the beginning, about the wisdom of adding a Bill of Rights to this Constitution. And the concerns didn’t spring from men who had reservations about “rights.” The concern rather was that a Bill of Rights would misinstruct the American people about the very ground of their rights.

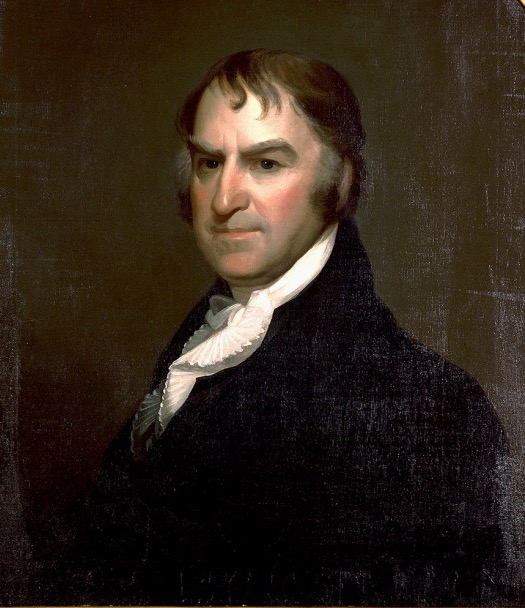

That concern is amply reflected in the line we hear so often when someone invokes “those rights we have under the First Amendment.” The hard question was put at the time by Congressman Theodore Sedgwick: Do you really think that, in the absence of that Amendment, you wouldn’t have a presumptive freedom, in a free country, to speak and assemble and publish? Why don’t you specify as well, he said, that a man has a “right to wear his hat,” or “that he might get up when he pleased and go to bed when he thought proper.”

Wouldn’t it make more sense to say that we have a presumptive claim to all dimensions of our freedom, whether grand or prosaic, whether the right to publish or braid hair, and that the burden should fall to the government to justify the restraints that it would place on these freedoms?

And indeed, one of the concerns at the time was that those rights set down in the text will always seem more important than those many freedoms that were left unmentioned.

When it comes, say, to laws imposing controls on wages and prices, the reflexive response has been: the right not to suffer those restrictions of freedom was never reserved against the government in the Bill of Rights, and so the authority to impose those laws must be part of the deep powers of the government.

In one of my books, I sought to pose the problem by offering two different laws or regulations. The first one bars obscene phone calls in the middle of the night. The second orders people to stay in their homes until given permission by their government to leave. One involves “speech” and so some would try to bring it under the First Amendment. The other involves a freedom never mentioned in the Bill of Rights.

And so the question: Would we actually allow the government to bear a much lesser burden of justification when it restricts our freedom to leave the house and move about in the outside world?

Who would have thought? Thirty years since I wrote those lines, we’ve had the question actually posed in the courts, as governments in the States have imposed lockdowns in the effort to deal with the contagion of COVID. In their duration and severity, those orders have run well beyond any precedents we have known in this country. But the powers of government to deal with the emergency have been assumed to be as large as the powers needed to deal with the crisis.

Still, those powers have not been unlimited. The classic case sustaining those powers was Jacobson v. Massachusetts (1905), a case on compulsory vaccination. As federal Judge Kyle Duncan reminded us in a recent case, the Court in Jacobson warned nevertheless that the police powers of the State may be engaged in ways “so arbitrary and oppressive in particular cases as to justify the interference of the courts to prevent wrong and oppression.”

Justice Alito gave a current and sharp expression to this concern in his dissent recently from the refusal of his Court to review the case of the Calvary Chapel in Nevada. The orders of the Governor blocked people from gathering in church even for a single service on Sunday. But at the same time, in Las Vegas, customers were free to roam, in larger numbers, from one casino to another day and night.

Alito insisted that “a public health emergency does not give Governors and other public officials carte blanche to disregard the Constitution for as long as the medical problem persists.” As he remarked, “the Constitution guarantees the free exercise of religion. It says nothing about the freedom to play craps or black- jack.”

Justice Alito was cited just this past week by a new, young federal judge, William Stickman, in western Pennsylvania, as he struck down the orders for lockdowns in Pennsylvania. The government had issued orders for people to stay at home immediately “except as needed. . . .[for] life-sustaining businesses, emergency or government services.”

Gatherings of more than 25 persons indoors were forbidden, along with outdoor gatherings of 250 persons. The judge found a critical want of clarity in the lines that marked “life-sustaining businesses,” apart from those many businesses that were palpably necessary in sustaining the lives of the owners and employees.

Some of these measures were eased and for a moment withdrawn, but they were still in force and could be resumed at any moment. These kinds of restrictions, said the judge, “were unheard of by the people of this nation until just this year.” And “beyond the right to travel,” as he said, “there is a fundamental right to be out and about in public.”

It was Theodore Sedgwick all over again: Did we really need to declare a “right to travel,” or “to leave our houses,” and a “right to go about in public”? We seem to know that we have those presumptive rights even though they are nowhere mentioned in the Constitution.

Now how do we know that – unless we had access to an understanding of right and wrong that was there before the Constitution and the Bill of Rights? And unless we still had that capacity to reason, with common sense, about the kinds of restrictions that may be justified or unjustified, reasonable or unreasonable, for people who were going about their daily lives doing legitimate things.

Which is to say, to the surprise of many lawyers, we’re back with the moral reasoning of the Natural Law, because we’ve never left it.

*Image: Theodore Sedgwick by Ezra Ames (after Gilbert Stuart), c. 1808 [National Portrait Gallery, Washington, DC]