Just after the Battle of Gettysburg, General Meade had not realized the full depth of the victory won by the forces of the Union under his command. He was still, in the aftermath, shaken by the severity of the casualties. But President Lincoln did grasp the moment at hand: He urged Meade to strike again at General Lee’s army, to destroy that army before it made its way across the Potomac River, back into Virginia.

Meade held back, and holding back, lost that moment. He sought, by telegraph, to give Lincoln this consolation: that the Army had been successful in “driving the invader from our soil.” From which Lincoln drew no consolation, but an exasperation getting familiar. He turned to his secretaries and said, “Will our generals never get that idea out of their heads? The whole country is our soil.”

When your own people begin absorbing the premises of the other side – that is a sign of trouble.

This matter came to mind again this past week as I took in a debate at the University of Dallas between two fine professors, dealing with an issue that has become curiously contentious: how our laws would be different if they were directed, by design, to “the common good.” One professor expressed his confidence that the American regime would be as durable as its founding principles, anchored in an enduring human nature. No one, he said, will be campaigning for public office on a platform of rejecting “unalienable rights” and the Bill of Rights.

I suspect that is true, but there is a risk of passing by one of the gravest lessons taught in political life: A regime may not be challenged frontally, with an overt attack on its defining principles. But a regime may be decisively undermined from within as political men – and judges – make the public more and more suggestible to premises that are quite at odds with the moral premises of the regime.

This was the work, as Lincoln said, of “the miner and the sapper.” Lincoln offered as a case in point, Senator Pettit of Indiana, who insisted that the self-evident “truth” of the Declaration of Independence was a “self-evident lie.”

That self-evident truth was that no man was by nature the ruler of other men, as men were by nature the rulers over horses and cows. The only rightful governance over human beings had to be drawn from the “consent of the governed.” Pettit was an officer of high standing in that government built on those premises of “all men are created equal.” Yet he expressed contempt for the premises on which his own authority rested.

If that moral erosion can take place among senators and presidents, does it come as a surprise that people in judicial office may draw us away from those founding premises just as well? Indeed, over the last 50 years, the courts have radically altered our understanding of that “human person” who is a bearer of rights and the object of the law’s protection.

In Lincoln’s time, it was his opponent, Stephen Douglas, whom he regarded as the “miner and sapper.” Douglas would argue, subtly and not so subtly, that the Founders didn’t really count black men as the men “created equal,” those beings who were the bearers, as humans, of natural rights. The question, said Lincoln, was “whether the negro is not or is a man. . . .[I]f the negro is a man, is it not to that extent, a total destruction of self-government, to say that he too should not govern himself?”

Conservative jurists in our own day speak of sending the question of abortion to the separate States to decide just whether the child in the womb is really a human being, with a claim to the protections of the law – as though there were no truth about the matter.

In the same way, Stephen Douglas made the case for federalism by pointing up the diversity of interests and manners. Indiana has laws favoring the local crop of cranberries; Maine has pine lumber. . .and some States simply have slave labor. Where, asked Lincoln, is the “parallel between these things and this institution of slavery?” To put these things on the same plane, as Lincoln said, was to liken slavery to morally “indifferent things” – and cultivate our own indifference.

With his powers of compression, Lincoln distilled Douglas’s position: “that if one man chooses to make a slave of another man, neither that other man nor anybody else has a right to object.” This is what has been heralded in our day as “privacy.” If people wish to deny the human standing of the child in the womb, and destroy the child as it suits their interest, no one else has the standing to object.

In that litigation over partial-birth abortion, the sainted Nick Nikas argued to Judge Bilby in Arizona that, in barring abortion at the point of birth, the legislators were trying “to erect a firm barrier to infanticide.” In rejecting that argument, Bilby conveyed in so many words that the barring of infanticide should not go so indecorously far as to inhibit abortion. But infanticide could cease in that way to be such a “big deal,” only if homicide itself was no longer a “big deal”—or unless the child in the womb didn’t count among the humans protected by the laws on homicide.

The Founders thought that the case for government by consent began with our awareness of what was evident, in nature, as a human being. But now the very definition of a human would depend on the “positive law” fashioned by judges and legislators – and without any standards of truth, outside the positive law, by which that positive law may be measured. And in that way, we talk ourselves out of the very premises of regime grounded in the rights that flow to human beings by nature.

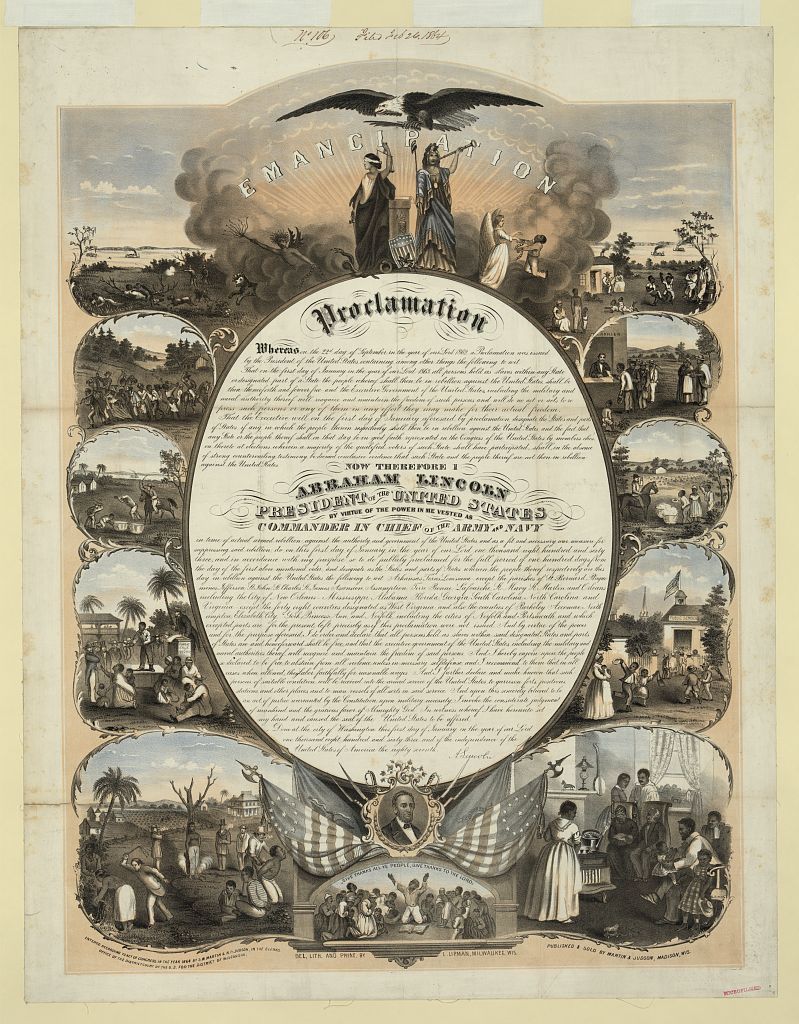

*Image: The Emancipation Proclamation, by L. Lipman Lithographers, Milwaukee [Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.]