For most Americans, the Fourth of July is a celebration of American “freedom.” Freedom is an iconic word for us. It’s also a foundational principle for Judaism and Christianity. But the political/philosophical and the theological meanings of the term are growing ever more equivocal. Perhaps of even greater concern, the average Christian or Jew doesn’t realize what’s happening or what’s at stake.

Is freedom an end or a means?

For many people, the former is problematic. The Judeo-Christian message is that God created us for the good, ultimately for the Summum Bonum, the Highest Good, i.e., God. Thomist philosophy identified the “ends” of the intellect as truth and of the will as “good.” When a person chooses to do something, he chooses to do what he regards as good. He may be mistaken, but human action always operates under the attraction of the “good.”

The very structure of language reveals this in-built bias: “Why did you choose A over B?” “Because A was better.” We understand why “better” justifies the choice. Someone who answered that he chose what was “worse” would raise the question, “Then why did you choose it?”

If the end of human action is the good, and not freedom, this also suggests some objective order of good and value that exists independently of the individual actor, towards which one has obligations to “do good and avoid evil.” The person does not stand neutrally before good and evil as equally legitimate choices, of equal weight on the moral scale. Man has a built-in, healthy orientation towards the good.

What, then, in the Judeo-Christian tradition, is freedom for? That question is actually quite acute because, in recognizing freedom as a means rather than an end, it recognizes freedom has a further goal. It’s for something. It’s for the good.

Human action has two effects: it does things in the world and shapes me. Taking my neighbor’s property without his consent does two things. It’s stealing and it shapes me: it makes me a thief. Moral action has both objective and subjective effects.

God gave us freedom as part of His image and likeness so that not only would things get done, but so that people would share in the goodness of what is done. Freedom is sine qua non to man as a moral being.

But this concept also entails the understanding that freedom put in the service of evil is not freedom. Such a use of freedom is self-destructive, eventually simply enslaving the doer and those he affects. Rather than expanding freedom, it destroys it.

The modern apotheosis of false freedom, treating freedom per se rather than good as the end of human action, denies all this. If such a notion even acknowledges the good (as opposed to “my good” and “your good”), any such good ultimately collapses into freedom itself: freedom is the good.

But, shorn of a further referent, there’s no basis on which to judge freedom: what was chosen is self-referentially “good.” There’s no “good” or “evil” out there to be chosen: the act of choosing itself defines good and evil.

This ethic has been most prominent in the debate over abortion and, more broadly, sexual ethics, largely because people have vested interests in the outcomes and the unborn don’t vote. Its implausibility as an ethical system is far more glaring in other areas, like property rights and “important things.” On life issues, the jury’s still out, depending on the convenience to be gained if a handicapped newborn or senile senior loses those things Jefferson quaintly styled “inalienable rights.”

To this ethic of radical freedom, Adam’s and Eve’s “disobedience” was a free choice to reject external constraints. In that perspective, it’s God, not they, who sinned, punishing them for choosing freely. This is neither Judaism nor Christianity.

This is why so many find Catholic former Supreme Court justice Anthony Kennedy’s “mystery of life” passage in Planned Parenthood v. Casey simultaneously so ludicrous and so monstrous: “At the heart of liberty is the right to define one’s own concept. . .of meaning, of the universe, and the mystery of human life.”

If we all self-defined meaning, Babel would look like a mere translator’s conference compared with the ensuing madhouse. It’s doubtful that many folk try to self-define the universe. . .or that the universe cares about the ravings of those who do. As for self-defining the mystery of human life, 60 million-plus infants slaughtered since Roe demonstrate the truth of Thomas Hobbes’ insight about unadulterated freedom: homo homini lupus. (“Man is a wolf to man.”) And so is a woman.

And yet the “freedom ethic” goes on, perhaps because the “dictatorship of relativism” balks at calling anything unequivocally good.

When I visited Central Europe in the early 1990s, just after the fall of the Iron Curtain, I argued that the local churches needed to undertake a catechesis of freedom. Many had successfully spent decades teaching people how to survive under slavery. But those people were unprepared for the moral challenges of freedom, especially because the freedom the West was selling was most often untethered to any objective good. “Liberal democratic freedom” traded on people’s aspirations for real freedom but gave them Esau’s mess of pottage for Jacob’s birthright.

What happened in Central Europe since has become a pan-Occidental crisis of freedom. We use the old word while wondering why modern “freedom” doesn’t fill us up, why it’s more like junk food empty of nutrition. Politicians trade on “defending freedom” in ways our forebearers would have recognized as degeneracy.

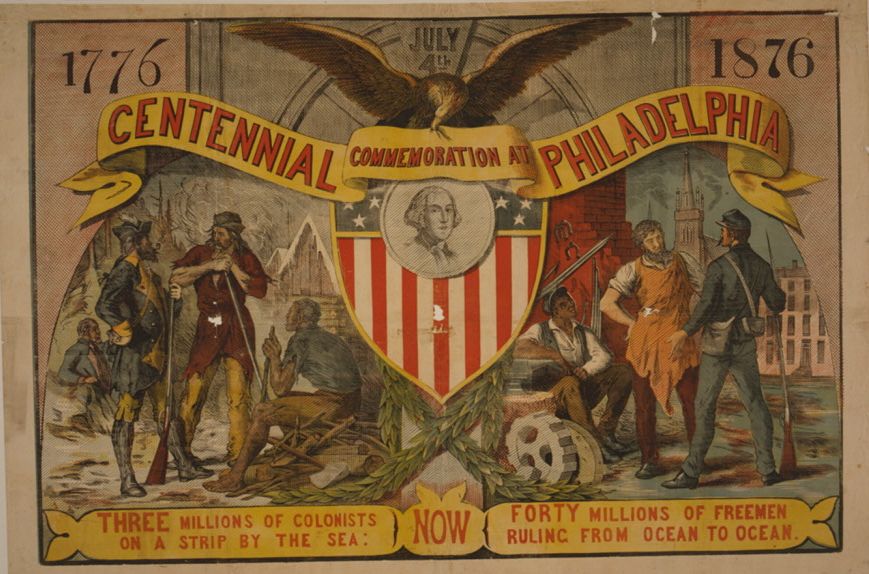

To promote religious liberty, the American bishops used to mark a “Fortnight for Freedom” just before Independence Day. It’s shrunk to “Religious Freedom Week.” We’re just three years away from the Semiquincentennial of the United States, the 250th anniversary of the signing of the Declaration of Independence.

Perhaps what we really need as we approach that landmark is a multi-year International Freedom Revival.

__________