Man’s life is like the flower of the field, says the psalmist, “for the wind passes over it, and it is gone, and its place knows it no more.”

That is not the psalmist’s last word on man, but we should pay heed to what he considers to be something profoundly sad, nor does he yet possess the revelation of eternal life.

He thinks instead of the children of those that fear the Lord, and their children’s children: that is a living place, beyond what the desert grasses have. And he understands that in his worship of God, he joins the immortal angels, “that excel in strength, that do his commandments, hearkening unto the voice of his word.” That too is a place, not to be despised.

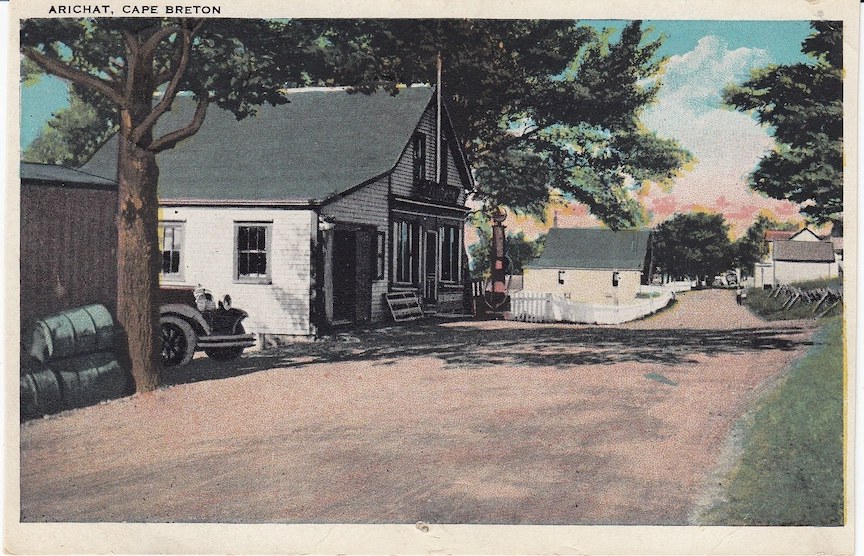

Here I am on an island in Nova Scotia, one that the privateer John Paul Jones once raided, an adopted place for my family, but a real place still, because the people still know one another in the present time and across the generations.

Today I sat on a porch with the first two people we met when we bought our cottage here in 2003, talking about what else but families, especially the forebears of the generous and extraordinarily skillful man who is helping us to restore a rectory that the diocese unloaded for, well, a couple of packs of bubble gum and a rosary.

His great-grandfather built the house, you see, so for him it is a labor of love, and he is grateful that we’re not the kinds who buy a house to gut it, so that it loses all its character, and it becomes a no-thing in a no-place.

The couple on the porch, Odilon and Elaine Boudreau, are devout Catholics, living almost opposite the island’s biggest church, which was once the cathedral for the diocese of Antigonish. I hope they won’t be embarrassed if I mention their names. They have fought the good fight to keep the church open, and have so far been victorious.

They have fought to keep its artistic treasures where they belong. They and their children have worked on the church, and I mean on – the roof, the walls inside and outside, and the ceiling, not to mention all the other tasks of cleaning, maintenance, and repair that an old and venerable building requires.

Odilon, meanwhile, is the go-to man for information on who is related to whom, and where your ancestors on the island are buried; and he has published a book on their particular Acadian dialect of French, so that words, phrases, and sayings may be remembered, things that don’t appear in any French grammar or dictionary you will use in school.

They have a place.

Here is an odd thing: the people on our island are not insular. I do not mean that they travel everywhere. Odilon doesn’t. Our neighbor’s sons, though, have gone out to work in the shale fields of northern Alberta. The lobstermen put out to sea. Many people have been to parts of the United States I’ve never seen. But whether they go places or not, they are all eager to welcome you if you visit or you take up residence there, even if it’s just for the summers.

Perhaps it’s a kind of confidence: the island was here when the first French and Basque fishermen used it as a stopping point to mend their nets and cure their haul; and the people sense that it’s going to be pretty much as it is now, long after they are gone.

Certainly many things have changed – everybody has a smartphone or a computer; but the families are what they are, interrelated, with long and shared histories, and almost everybody dwells within the long arc of the church, even those who do not show up for Mass on Sunday.

“No man is an island,” said the Reverend Donne, but modern life seems organized to prove him wrong, by making each one of us an insular zone of desire; and our places know us no more, because there are no more places at all, at least not human places as opposed to geographical intersections of latitude and longitude.

Symptomatic of the contempt for place: laying highways that cut old neighborhoods in half, effectively destroying them; zoning laws that make walking to a small grocery store impossible; college admissions giving the stiff arm to local students; and yes, our own Church, advising us that mere buildings are of no importance, and forgetting that for human beings, any place where people have come together to worship God can never be a mere building.

Forgetting also that if people are going to have a place to enjoy a full human life, there must be places, not mere locations, just as there must be families and interrelationships among families, not just pin-pricks of procreation here and there.

I am not speaking here as a traditionalist but as a human being. In John Webster’s revenge tragedy, The Duchess of Malfi, the villainous Cardinal dies remorseful and unrepentant, with words that express the emptiness of his despair, for he and his wicked brother have murdered their sister: “I pray now, let me be laid by, and never thought on.”

In an earthly sense, the Cardinal’s fate is now almost everyone’s, and not at death only but here and now. We need to live in a place, to be known there, and our families also to be known, unto our children and our children’s children. God did not mean us to live like dogs, or dry grass.

The Church must be at the center of any recovery of place, as she must be at the center of the recovery of that battered and bloodied institution, the family. As long as she insulates herself in a vast global bureaucracy, or a bureaucratic globalism, it will not happen. Beelzebub does not cast out Beelzebub.

“I go before you,” says Jesus, “to prepare a place.”

__________