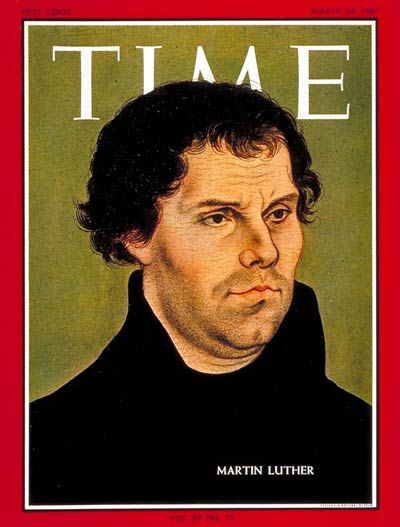

Today marks the five-hundredth anniversary of Martin Luther’s (alleged) nailing of his ninety-five theses onto the church door of the castle at Wittenberg, setting off the Reformation. In 1999, Catholics and Lutherans passed the theological peace pipe, issuing a joint declaration stating that the two Christian branches actually agreed on the very point over which Luther had broken with the Catholic Church: that “justification” – that is, the forgiveness of human sins through Christ’s saving power, is attainable solely through God’s grace, not through human merit as some Catholics had argued (or seemed to argue). Then, on Oct. 19 of this year, Italian Bishop Nunzio Galantino, secretary-general of the Italian bishops’ conference, took it another step and declared that Luther wasn’t even a heretic and that the Reformation was the “work of the Holy Spirit.” Now, I wouldn’t go that far – but I feel some sort of ecumenical obligation to say something nice about Martin Luther.

The trouble is: it’s hard to think of anything. You don’t have to subscribe to Young Man Luther-style armchair Freudianism to conclude that Luther was a mess. He was arrogant, self-absorbed, self-dramatizing – and thought the world revolved around him personally because he was smarter than and spiritually superior to everyone else.

He spent his young adulthood dithering about what to do with himself (and wasting his father’s university tuition money) in an age – the late Middle Ages – when young adults couldn’t afford to dither because most of them didn’t make it much past age 40. Then, when he finally entered an Augustinian monastery (in one of his typical melodramatic gestures: You will “not ever” see me again), he wallowed in misery for a decade because he couldn’t get a guarantee that his soul would be saved – a sin against the Christian virtue of hope.

When it came to “reforming” the Church after 1517, what Luther really wanted wasn’t, say, getting rid of selling indulgence or “not ever” being seen again. Luther was seen. Everywhere: hobnobbing with powerful German princes who had beefs against the Holy Roman Emperor, helping them confiscate monasteries right and left (didn’t Luther have one single fond memory of the Augustinians he’d lived with those many years?), and viciously persecuting the Anabaptist ancestors of those nice Amish ladies who sell heirloom tomatoes at my local farmers’ market.

Luther preached sola scriptura, but he freely messed around with the Bible when it didn’t suit his theology. He inserted the word “alone” after the word “faith” into his German translation of Paul’s Letter to the Romans and tried to relegate the Letter of James to second-class status because it mentioned good works. When it came to getting married, he couldn’t just settle for a nice German burgher’s daughter. He had to marry an ex-nun, Katharina von Bora, whom he had personally lured out of her convent.

How in-your-face against the Catholic Church could you get? The two of them moved into a confiscated monastery, which was like evicting your neighbor so you could grab his house. Luther was single-handedly responsible for the wholesale destruction of priceless medieval art, as countless brand-new Lutherans gleefully whitewashed over the frescoes in their formerly Catholic churches and threw images of the saints into the fire. Fortunately, Luther wasn’t an Italian, so we still have some Giottos around.

He also had a weird scatological fixation, with quite the bathroom mouth when it came to insulting his enemies, which he did frequently because he made a lot of them. And to top it off, he was ferociously anti-Jewish. Granted, medieval Catholics were no great shakes when it came to treatment of the Jews, but at least at least none of them wrote a tract titled On the Jews and Their Lies that was one of Julius Streicher’s favorite books.

And Martin Luther did not invent the Christmas tree. He did not write “Away in a Manger.” He did, however, all but succeed in wrecking Halloween, renaming it Reformation Day. What a killjoy. Couldn’t he have nailed up those ninety-five theses on October 30 instead?

In all fairness, there actually are a few good things to be said about Martin Luther. I’m listing them here:

- Selling indulgences really was a bad idea. If only he had stopped there.

- He was devoted to his children. That’s nice.

- Katharina von Bora was said to brew excellent beer – but I bet she picked up that skill in the nunnery.

- “A Mighty Fortress Is Our God” (which Luther did write) is a terrific hymn.

- J.S. Bach was the greatest composer who ever lived. Søren Kierkegaard was one of the greatest theologians. Dietrich Bonhoeffer was one of the noblest Christian martyrs.

- The present-day Lutherans who have made the Midwest a bastion of social conservatism (and excellent public schools) are the salt of the earth – although those cream-of-mushroom casseroles and Jell-O salads they serve at church suppers leave something to be desired.

At this point, my Protestant and evangelical readers might be thinking that I’m simply a latter-day Father Feeney, railing indiscriminately against “our separated brethren,” as we Catholics call them nowadays. Not so. My husband is a Prot! And my hat is off to the Wesley brothers, William Wilberforce, C.S. Lewis, Billy Graham, evangelical Anglican biblical scholar N.T. Wright, and many, many other witnesses to vibrant Christian faith outside the Catholic Church. I don’t agree with their vision of what Christ’s church is or should be, but I resonate profoundly to their intense relationship with Christ himself.

I just wish the whole thing hadn’t been started by . . . Martin Luther.