Visiting the dentist is rarely an exercise in metaphysical imagination. My dentist, though, has painted the ceilings of his offices with various aphorisms, no doubt to distract us poor (and reclining) patients from the rigors of oral onslaughts.

Among the various slogans I read while trying stoically to put up with the scraping, drilling, and “irrigation” (they actually use that noun) incidental to my visit, there was this: “Live life without regret.”

I think, though, that seeking to live life without regret is both impossible and undesirable.

Although St. Paul teaches us that we are wise in “forgetting what lies behind and straining forward to what lies ahead” (Phil 3:13) and that “godly sorrow produces a salutary repentance without regret” (2 Cor 7:10), one should understand those pericopes in light of traditional Catholic teaching. As Mass begins, for instance, we are urged in the Penitential Act to “acknowledge our sins and so prepare ourselves to celebrate the sacred mysteries.”

This does not mean that I am to dwell on my sins (which God can forgive through His priest in the sacrament of Confession) but, rather, that I understand that “I have greatly sinned, in my thoughts and in my words, in what I have done and in what I have failed to do, through my fault, through my fault, through my most grievous fault.”

My sin is actual and personal. I have failed to think (see CCC 1327), to speak, or to act in ways conforming to God’s will (cf. Romans 12:2). As the holy sacrifice of the Mass begins, I recognize, in sorrow, that I am a sinner in need of God’s grace and mercy. In other words, I regret the many times I have strayed from the path of God.

To regret means to “feel sad, repentant, or disappointed” about something. The Church teaches that sorrow – and fear of the Lord – may be filial or servile. The latter (see CCC 1828) produces a contrition that is based upon worry about going to Hell (a fear that is still spiritually sensible). The former, and preferable, contrition proceeds from my deep regret that, in thought, word or deed, I have ignored or betrayed Our Lord. Thus the words of the traditional Act of Contrition: “I detest all my sins because I dread the loss of Heaven and the pains of Hell but, most of all, because I have offended Thee, my God, who art all good and deserving of all my love.”

Victor Hugo once wrote that “Sorrow is a fruit. God does not allow it to grow on a branch that is too weak to bear it.” We cannot have true contrition for sin unless we have the strength to repent (cf. Mark 1:4), confess our sins, have a firm purpose of amendment, and try as best we can (in practice or in prayer) to give satisfaction or to repair the damage we have done.

Regret, remorse, and repentance are synonyms for “a radical reorientation of our whole life, a return, a conversion to God with all our heart, an end of sin, a turning away from evil, with repugnance toward the evil actions we have committed.” Such regret, says the Catechism, “is accompanied by a salutary pain and sadness which the Fathers called animi cruciatus (affliction of spirit) and compunctio cordis (repentance of heart)” (#1431).

The fear, the pain, and the sorrow I ought to feel at having wounded Christ are dissolved in the ocean of His divine mercy. Regret summons me to recall the pattern of my sin and to resolve, by the grace of God, not to repeat it. (cf. Isaiah 41:10 and James 1:2-4) And trust in God’s love similarly summons me to conviction that God will forgive every sin if we turn to Him and turn away from evil. (1 John 1:9)

To “live life without regrets” is impossible because we are imperfect. There are thoughts, words, and deeds which all of us must repent. “Regrets, I’ve had a few but, then again, too few to mention,” sang Frank Sinatra in the incalculably pompous song, “My Way.” In Edwin O’Connor’s wonderful old novel, The Last Hurrah, the story’s hero, Mayor Frank Skeffington, lies dying as friends gather around, and one old political rival, who announces that if Skeffington had it to do all over again, he’d do it very differently. We want to cheer as Skeffington marshals the strength to say, “The hell I would!”

As much as we might admire the pluck of Frank Skeffington, we should, if granted a second or third or fourth chance to correct our errors, resolutely do so, secure in the knowledge that virtue often proceeds from regret rightly acted upon. Regret – accompanied by restitution and resolve – are not undesirable, but, on the contrary, are the wellspring of the examined life which, in turn, leads us to know, love, and serve God.

In 1984, Pope John Paul wrote (in Reconciliation and Penance): “The restoration of a proper sense of sin is the first way of facing the grave spiritual crisis looming over man today. But the sense of sin can only be restored through a clear reminder of the unchangeable principles of reason and faith which the moral teaching of the Church has always upheld.”

To have “a proper sense of sin” leads to the regret that converts sinners into saints. As we approach the remembrance of Christ’s death and resurrection this week, we should also keep in mind that through Him regret can be transfigured into joy.

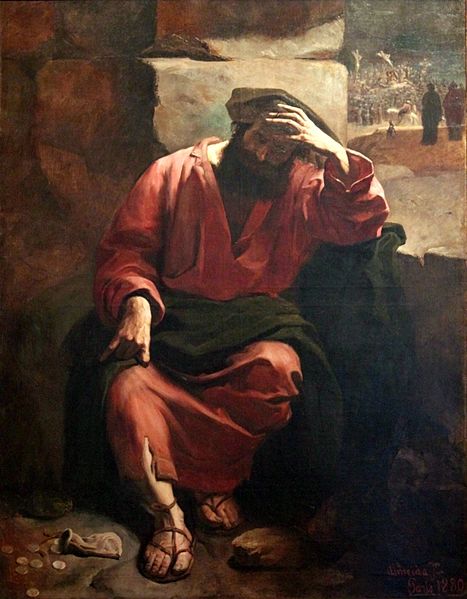

*Image: The Remorse of Judas by Almeida Júnior, 1880 [Museu Nacional de Belas Artes, Rio de Janeiro]