Nobody likes long airport layovers, but sometimes they are a blessing. Flying to Africa typically involves going through a European capital, arriving early in the morning and then catching another redeye flight much later that night. This schedule has given me great opportunities, e.g., to go from Heathrow into London, and spend the day at the National Gallery.

The Prado is probably my favorite art museum. I agree with James Michener, who wrote in his book Iberia: “If I want to see eight top paintings, I go to Venice. If I want to see eighty, I come to the Prado.”

But the sheer range of work in London’s National Gallery is astonishing. To behold it is to grasp that the backbone of Western Civilization is, of course, religious, no matter how obstinately it is denied.

I found myself lingering before Caravaggio’s “Supper at Emmaus” and Honthorst’s “Christ before the High Priest.” Front and center of the latter is a single candle that casts light on the drama of God facing the interrogation of one of His creatures. A preacher would be hard pressed to convey that God came to redeem humanity, in all its insolence, with more immediacy.

Encountering gems like this in London, you can’t help but wonder about the countless artistic treasures inside Catholic churches that were destroyed during the Reformation.

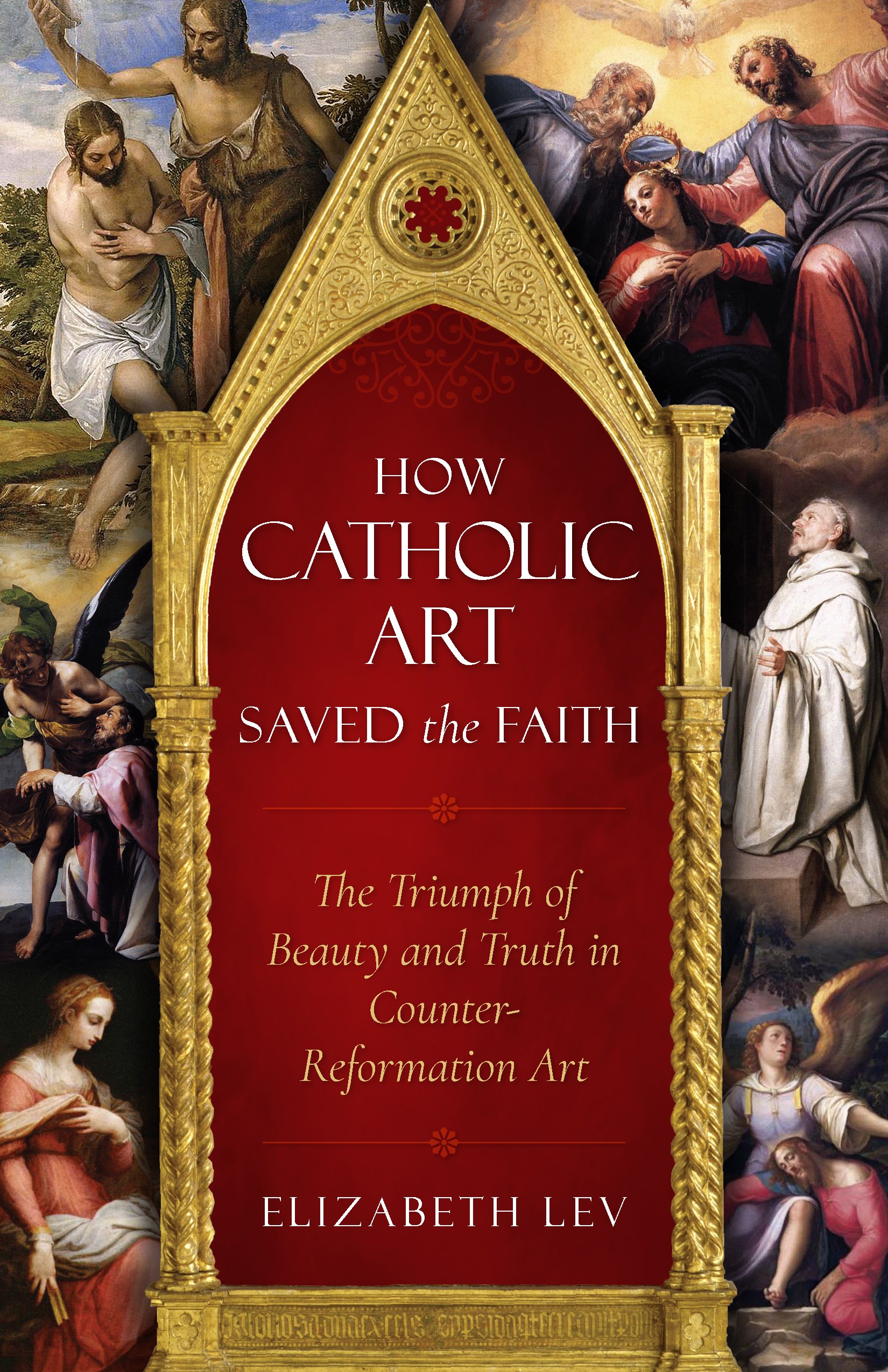

I can’t say I know a ton about art, which is one reason I’m grateful for Elizabeth Lev’s new book How Catholic Art Saved the Faith: The Triumph of Beauty and Truth in Counter-Reformation Art. As the title suggests, Lev organizes the book around particular areas of Protestant departure from perennial Catholic doctrine and provides an absorbing account of how art was deployed as an instrument to reinforce it. Differences in doctrine remain highly consequential in the lives of individual men and entire nations, even if they are deemed marginal today.

Broadly speaking, Lev treats the sacraments, intercession, and man’s cooperation in salvation, as depicted in commissioned artistic output mostly between 1570–1650. This undertaking, prompted by that particular historical moment, nevertheless has enduring relevance. Indeed, Lev writes that the challenges faced by Catholics back then have a “striking similarity” to the ones they face today.

If anything, that seems like an understatement. Our age is besieged not so much by differences within Christianity, which are regarded as irrelevant to the comforts and maxims of modern life, but by an all-out renunciation of Christianity. Moreover, we seem as receptive to beauty as we are to reason, which is to say hardly at all.

Nonetheless, it is true that beauty can still persuade in an instant, and we do soak things up visually; we “prefer seeing the movie to reading the book.” Though our cultural milieu makes it a tall order, Lev is right to say art still has the capacity to uplift, to clarify, and to evangelize.

If Protestants of that time felt the Sacrament of Reconciliation was not really necessary, our modern day alchemists have not just renounced the notion of sin but imagine they have transformed it into a positive good.

Lev describes how, a few short years after the Council of Trent, Titian painted “Christ and the Good Thief” in such a manner as to evoke central aspects of the Sacrament of Reconciliation. He chose an angle whereby only these two are shown on their crosses, with Christ’s head tilted towards the good thief (as a priest’s would be in the confessional), bestowing mercy to the one who had confessed his iniquity. Only one of Christ’s arms is visible because it is stretched out directly towards the viewer – an invitation to accept His astonishing redemptive offering.

If a clear explanation of what this sacrament does for the human soul and a visual depiction of it does not nudge you towards welcoming the gift that it is, it is hard to know what would.

In response to vehement Protestant repudiation of Purgatory, St. Robert Bellarmine offered a written defense, while Carracci painted “An Angel Frees the Souls of Purgatory.” It’s a stirring work, and Lev provides insight that might not be readily apparent – a recurring, rewarding feature of this book. While freeing a soul with one arm, the angel is also pointing upwards with the other towards St. Augustine, positioned beside Mary and Jesus, because he wrote “the Treatise on Caring for the Dead.” The other figures depicted in the celestial realm were chosen because they too were known for defending Purgatory.

Was the Immaculate Conception, which Calvin mocked, simply “an invention of monks”? A succession of artists would defend the idea, emphasizing one feature here, another there, but typically depicting Mary as the “woman of the apocalypse in Revelation” (12:1). There are renditions that have Mary standing on a full moon. But in each of the three examples that Lev includes – Bartolomé Estaban Murillo’s version (c. 1660) is probably the most famous – our Lady is standing on a crescent moon.

That detail surely has an additional significance that Lev does not mention: the crescent moon is the symbol of Islam, a point that would not be lost on Spaniards, who had endured centuries of Islamic oppression. And that this history is lost in most of Europe today is one reason it stands in such peril.

The whole concept of Mary as our great Advocate – to which another chapter is devoted – is largely lost on many Americans, or at any rate seems hard to grasp for those steeped in Protestant cultures. But Lev notes that Mary had been depicted for centuries graciously interceding on behalf of the populus; this endearing image, along with corresponding “centuries of accepted practice in prayer,” was harder to overcome than any particular Marian doctrine.

The book ends with Lev’s treatment of Michelangelo’s “Last Judgment” – “the ultimate Catholic response to the Protestant Reformation” – short biographies of several artists, and a recommendation most readers are in position to carry out: place some beautiful Catholic art within the home.

*Images in this column: 1. Christ before the High Priest by Gerrit Honthorst, c. 1617 [National Gallery, London] and 2. An Angel Frees the Souls of Purgatory by Lodovico Carracci, c. 1610 [Pinacoteca Vaticana, Rome]