Chronological bigotry – blind opposition to what is old, default preference for what is new – was illustrated for me by a young guide, showing me around parts of a Catholic college.

It had old and new sections. The former was a single, towered, neo-Gothic structure, chiseled of impregnable stone. A few decades ago, this impressive building was the whole college, with its statuary, and its contained chapel still with modest rood screen and other backward touches. Happily, my guide through THAT part of the institution was an elderly priest, not looking for controversy on any point, but well acquainted with the lost customs.

The old college had once been fairly crowded, apparently with memorable characters – ghosts in clerical dress – monks in their cassocks, nuns in their habits – even secular academics in gowns. Studious quietness; mutual respect. The timeless qualities.

The new buildings, the product of much-moneyed benefactors, sprawled beyond this original building. They were oriented in different directions, and plentifully served with parking lots. And flimsy: I saw walls that I could punch my fist through. Janitors, keeping the residences clean. Little computers, not books, on the tables. Tee shirts, even on the girls.

The landscaping had all been done suddenly with mighty earth-moving machines; the buildings themselves were partly pre-fabricated. Their design was not aggressive “starchitecture,” as we see on more fashionable campuses; merely suburban and mediocre. But millions and millions had been spent nevertheless, on a swelling student body, leaving lots of empty floor space for further expansion.

It seemed to me a high-tech refugee camp, or some other large waiting station.

Whereas, in the old college, there had been attention to craft and detail in each square foot. Permanence was on display. The only slapdash was in recent safety features: no effort whatever had been made to match the unifying form, or very solid materials of the venerable building; only visual “sore thumbs” scattered here and there.

Everything in “the new” was put up, or plugged in, the day before yesterday. It will all need not repair but replacement a few decades hence. I noticed a ceiling with water-damage spreading; already, cracks. Nature could render this place uninhabitable (except by wildlife) in a season or two. It will leave no ruins.

(In my sixties, now, I see things built at extravagant cost in my childhood, being demolished as a matter of course.)

Gentle reader, if he has spent much time in “post-secondary institutions,” or anywhere else, will surely know this scene; especially if he suffers from keen eyesight. The old masonry lifts the heart, or at least tries to do so, even where it is cumbersome and Victorian; the new makes one bleary.

The thinking heart that is lifted moves closer to God; the heart that is not moved thinks, only, “Where do you get coffee around here?” (Aha, the Starbucks is over there!)

The young guide was also unlike the old. She seemed almost (but not quite) proud of all the spanking newness. When pointing us towards the original college, she actually apologized for it being out-of-date.

I reflected that it would take major planning permission to take it down. A lot of pricey committee work. Bureaucracy preserves through its own ineptness.

As an afterthought the young lady added, “But it is beautiful.” A wonderful concession on her part.

Tradition sustains, revolution destroys.

Beauty also sustains. It gives life. The man or woman surrounded by beautiful things is, consciously or unconsciously, uplifted by them; moved closer to God, almost involuntarily. Grace moves mysteriously through our ancient buildings, and could do through our modern ones, too – if they were beautiful.

What I mean by this word is not “pretty” or “cool,” let alone “functional” – unless we allow that a function can have spiritual as well as “practical” meaning. Something that gets the job done, and is then disposed of, cannot partake of beauty, or peace. It will itself become – rather IS from the beginning – part of the “environmental problem” it may have been designed to address.

I am using big words that I hope will resonate. “Environmental” is five syllables’ worth. The word now carries ideological freight; it defeats its own original purpose. It implies, as all our modern concepts do, progress or regress. It makes everything timely. It is impossibly mixed with such concepts as economy and hygiene. It turns beauty into an afterthought.

It was the wisdom of the ancients – not only the Christian ones – to seek beauty in every public and private facing. The human instinct used to make each object look fitting to its task.

A cathedral, for instance, is designed to be “fitting” in this way. Form followed function at Chartres, perfectly. The Chinese gave us the cult phrase, “feng shui,” and others the tutoring in geomancy that we find rather puzzling today, and of course “unscientific,” therefore trivial.

To us, the whole built environment is trivial, for in the contemporary inversion of values, we reject mere things. The material has been spiritualized in a nihilistic way. Nothing that is made by human hands can have any intrinsic importance, except insofar as it advances our progressive faith and beliefs.

Yet any genuine progress is cumulative. The “science” we worship is an accumulation of discoveries that were not lost. Every advance was from an earlier advance, and thus “traditional” in the most exacting sense.

He who re-invents the wheel is merely spinning. The person who condemns the wheel, because it is so old and boring, is not only revolutionary but demented.

The same is true in the “aesthetic” dimensions. We build on what we have not lost. We – should we happen to be sane – create in view of what has been created.

It seems to me that the wheels have come off our cultural imagination. No wonder that our “progress” only degrades us. It drags us down.

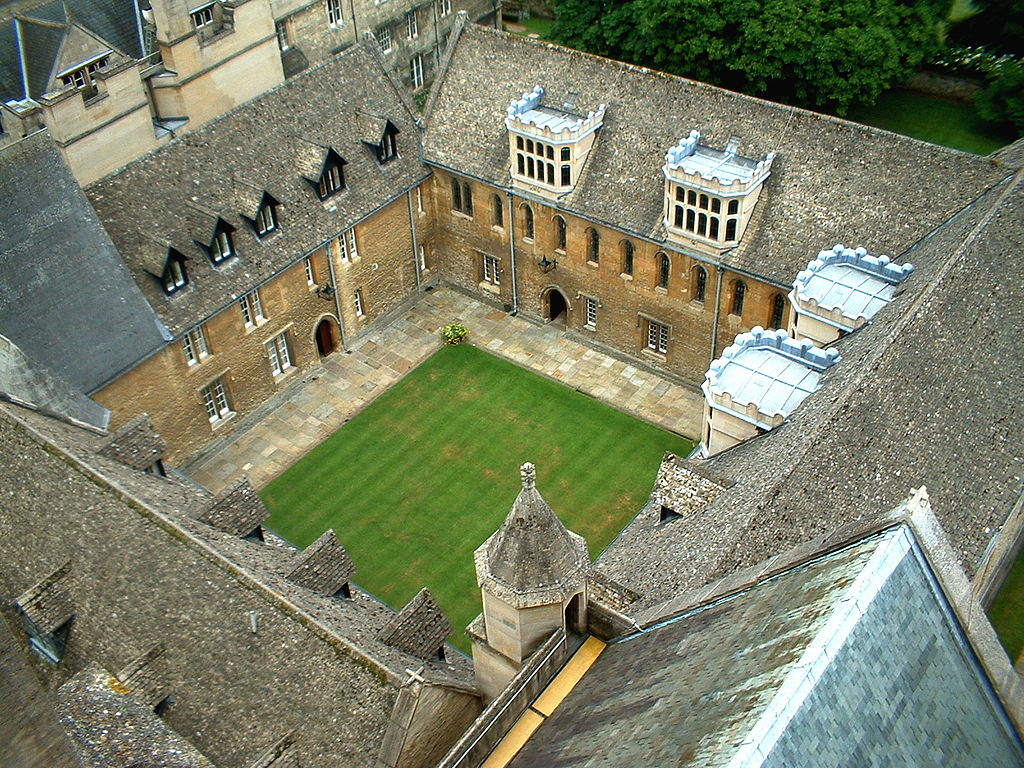

*Image: The Mob Quad at Merton College, Oxford (built c. 1378).