My first experience of death – not of another but of myself – occurred when I was nine years old. I remember it vividly, now more than sixty years later.

At the time, abdominal pain was new to me. Of pain, generally, I had been taught not to complain, in the Catholic school to which my rather post-Protestant parents had entrusted me. This had little to do with religion; we were told that it was unmanly to whine, and one should accept the occasional beating.

Perhaps the religious would rise to “taking one’s lumps” for Jesus. We pagans would simply take our lumps.

So I was experiencing this pain on my own.

It was winter, back in Canada. Christmas had just passed, and everyone else was merry. I was earning a reputation for seriousness. For some reason, as the pain began to “blossom,” the thought that it would be my last Christmas, came into my head.

Dressing warmly, I walked out in fairly deep, accumulating snowfall, in order to be alone. My plan was to wish good-bye to the house and the yard in which I’d been living. I was not feeling strong enough to walk my valedictions any farther.

The sight of our back porch is what principally has stuck with me. My father had been rebuilding it in the autumn. It was, to my little mind, a symbol of all the things that are done in this world.

My mother, a registered nurse, noticed my pallor when I came back inside. She asked me what was wrong, and began to examine me in deadly earnest, until she found a clue. She got right to a telephone and called Dr. Macintosh.

These were the days when doctors, including those who did some surgery, came to your house. I was beginning to pass out when he arrived. Dr. Macintosh and I were then whisked off to the hospital, in my father’s Volkswagen.

Apparently, my appendix was infected and about to burst. The doctor would remove it, but all I saw was the cup sliding over my face, that enclosed me in anesthesia.

Modern medicine was a wonderful thing, even in 1962. The idea that a medical man could re-edit a body, deleting any malign bits, thus saving a patient’s life, would have impressed the practitioners of previous generations. Yet for all the exciting new technical abilities, people still died.

But not this nine-year-old. I had cheated death.

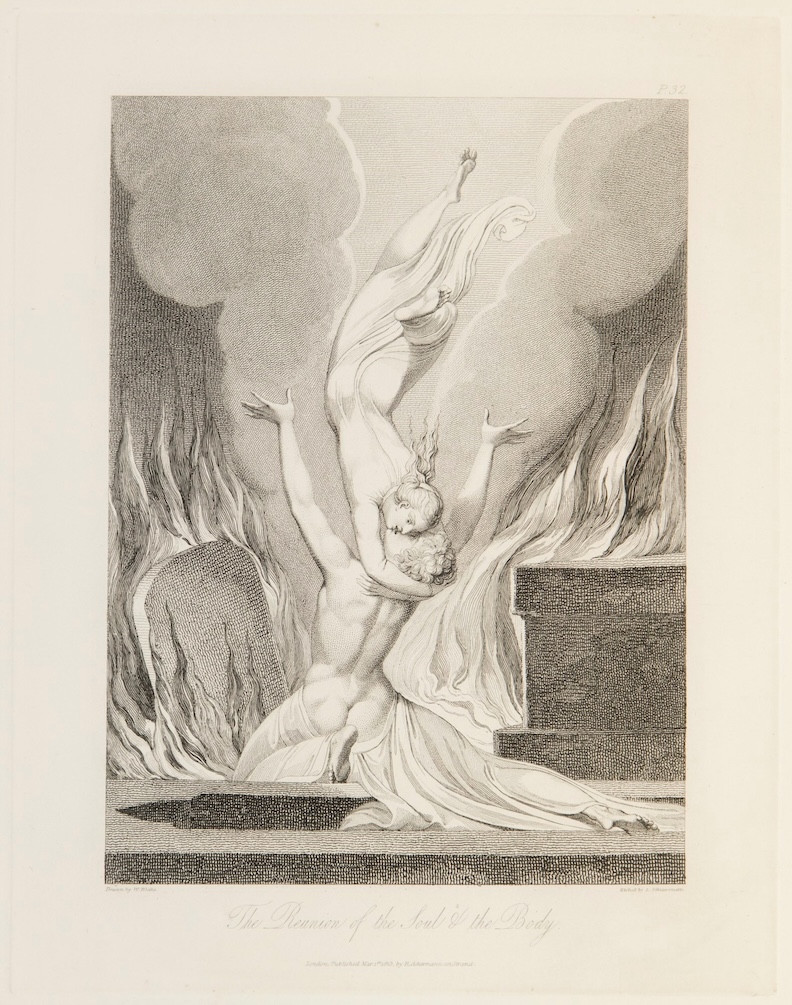

When I “came to,” surrounded by familiar persons, I could not doubt that I was back in the world. Where I might have gone, instead, was a thought unformed, nor could it be formed. I think the child knows there is a world beyond death, with instinctive certainty. But that is probably all he knows.

Over the time since, as the result of one unintentional adventure or another, I have nearly died a few times more. Of course, I mean only a plausible chance of death; of being in a situation where one can expect to die. I have no idea how often this happens to others, but I suspect it occurs at least once in most lives.

In each of my cases, my mind turned back to the first case, and I thought, timelessly, “I know this place.” It was déjà vu, or déjà rêvé – oh dear, all over again.

Standing, and looking at, but not through, the portal from which no man returns. . .not even those who consult Ouija boards. There is a moment of crossing over that has, until now, always been interrupted, for everyone alive.

The last time I had the sense that death was approaching (more a “was” than a “might be”) happened during a heart attack, three years ago. Before the anesthesiologist on the operating table, I had that nine-year-old moment again. I “fell asleep,” but again, I survived.

And again awakened, dazed from the sedation, and apparently a stroke. I set about collecting all the shattered pieces of my consciousness.

I was asked by my sister if, while proximate to death, I had had any glimpse of an afterlife. I had not. In strange hallucinations afterwards, however, several of the dead, including my late mother and aunt, called at my bedside. But drugs were a ready explanation for this.

Consciousness presents many interesting and amusing problems. To this day, I recall hallucinatory narratives quite sharply, and the dramatic plots and humorous twists in which I participated, better than I remember anything else from “intensive care.”

I call to mind the mangrove swamp (with giant lizards) twenty floors below the window. Yet I was never near a window, and only four storeys up.

Only towards the end of the experience was I beginning to sort out who the imaginary characters were, and distinguish them from mundane hospital staff. I was swimming again, in the dull dishwater of reality.

The dramatic and thrilling life could only continue if I devoted my remaining years to ingesting hallucinogenic drugs. This was tempting, but instead, I resolved to take only the boring medications a general practitioner prescribed for me.

I went backwards, into life, and I returned to the puzzlement I had long felt about futurity. For my faith, such as it is, does not cure this. It gives no certainty about what events will be, only certainty about the identity and loving nature of the divine.

There are no “sneak peaks” except such as have been revealed to a few of the world’s most profound mystics. To expect a genuine vision is to expect a miracle. And miracles do happen, but they happen TO us; they cannot be ordered.

And we must await what we cannot know, wearing the blinders of our biological existence. For what we see, beyond the blinders, is like that mangrove swamp and the visitations of ghosts. It is only what appears by our own contrivance.