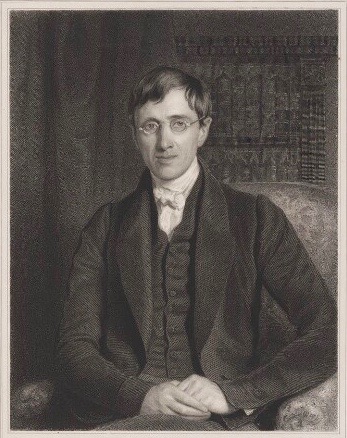

Blessed (soon to be Saint) John Henry Newman (1801-1890) developed necessary but not sufficient “tests” or indications for distinguishing true and false doctrinal development in his well-known 1845 work, Essay on the Development of Christian Doctrine. There are seven of these “tests”: Identity of Type, Continuity of Principle, Assimilative Power, Logical Coherence, Fecundity, Conservation, and Vitality.

They are necessary but not sufficient because “ecclesial warrants” (as Thomas Guarino calls them) are also necessary to assess doctrinal development. Warrants such as Sacred Scripture, ecumenical councils, doctors of the Church, the Christian faithful, and the Magisterium. Still, all these “tests” and attendant warrants help us to distinguish “development” from change, i.e., proper growth in understanding, which may involve correction, modification, and complementary formulations, from improper mutations and corruptions.

In particular, Newman says, “A true development is that which is conservative of its original, and a corruption is that which tends to its destruction.” (emphasis added). The “continuity of principle” and “identity of type,” or what Oliver Crisp calls a “dogmatic conceptual hard core,” is what Newman refers to when he speaks of what must be conserved.

Fundamental to doctrinal development is the idea of “propositional revelation.” Newman held that revealed truths, what he called “supernatural truths of dogma,” have been “irrevocably committed to human language.” God’s written revelation, according to Ian Ker’s reading of Newman, “necessarily involves propositional revelation.” This propositional revelation in verbalized form, or what Newman called the “dogmatical principle,” is at once true though not exhaustive, “imperfect because it is human,” adds Newman, “but definitive and necessary because given from above.”

For example, Jesus Christ reveals to us the truths about marriage by referring us back to the creation texts of Gen 1:27 and 2:24. Here we have Newman’s “dogmatical principle” at work. “Male and female he created them” and “for this reason . . . a man will be joined to his wife and the two [male and female] will become one flesh.”

Marriage is a two-in-one-flesh union between a man and a woman.The truth of this judgment is grounded in objective reality, according to the order of creation – the way things really are. Its contact with reality is the basis of this teaching’s vitality. Jesus unites into an inextricable nexus the concepts of indissolubility, twoness, and sexual differentiation, and hence we have the “identity of type” that must be conserved in the development of doctrine.

These texts are absolutely normative for marriage, indeed, for the Christian anthropology that ungirds sexual ethics, according to the Catechism of the Catholic Church. (§§2331-2345)

John Paul II explicitly states a foundational principle of Christian anthropology: “In fact, body and soul are inseparable: in the willing agent and in the deliberate act they stand or fall together.” (Veritatis Splendor §49). This principle has been developed by affirming sexual differentiation and hence the bodily nature of the human person as constitutive of marriage.

The sexually differentiated bodily sexual act is such that, as a foundational prerequisite, it is intrinsic to a one-flesh union; and hence the form of love that is marriage is not detachable from its foundation in a bodily sexual union of man and woman.

The moral and sacramental significance of this principle has now received explicit attention in view of the anthropological challenges of the sexual revolution, namely, the claims that sexual differentiation and hence the bodily nature of the human person are insignificant.

The denial of the continuous validity of this principle – by homosexualism, same-sex blessings/marriage, transgenderism – is a corruption of dogma since it asserts the contrary of the teaching’s “dogmatic conceptual hard core” on marriage, which regards sexual differentiation as a fundamental prerequisite for attaining the two-in-one-flesh union of marriage. (Gen 1:27, 2:24)

Furthermore, John Paul II has richly developed this emphasis on the founding principle in Christian anthropology, namely, that the sexually differentiated body is intrinsic to one’s own self. He showed in his seminal works – Love and Responsibility, Man and Woman He Created Them: A Theology of the Body, and the Acting Person – both the assimilative power and fecundity of this anthropology. Thus, he synthesized personalism, existential/hermeneutic phenomenology, and Thomism into a coherent whole.

This synthesis involves a logical type of development in which the substance (Newman’s “identity of type” and “continuity of principle”) of revealed truths is expressed differently in a linguistic and conceptual way but states the same thing about the human person. In other words, alternative formulation must always be in eodem sensu eademque sententia, that is, according to the same meaning and the same judgment of truth.

Thomas Guarino has argued in his magisterial book, Vincent of Lérins and the Development of Christian Doctrine, that Newman is clearly inspired by Vincent. So, too, is Vatican II. John XXIII in Gaudet Mater Ecclesia (his address opening the Council) said. “For the deposit of faith [2 Tim 1:14], the truths contained in our sacred teaching, are one thing; the mode in which they are expressed, but with the same meaning and the same judgment [eodem sensu eademque sententia], is another thing.”

The subordinate clause in this passage is part of a larger passage from the constitution of Vatican Council I, Dei Filius, and this passage is itself from the Commonitorium primum 23 of Vincent of Lérins: “Therefore, let there be growth and abundant progress in understanding, knowledge, and wisdom, in each and all, in individuals and in the whole Church, at all times and in the progress of ages, but only within the proper limits, i.e., within the same dogma, the same meaning, the same judgment” (in eodem scilicet dogmate, eodem sensu eademque sententia).”

Although the truths of the faith may be expressed differently, the Church must always determine, in light of the ecclesial warrants listed in the opening paragraph, whether those new re-formulations are preserving the same meaning and judgment (eodem sensu eademque sententia), and hence the material continuity, identity, and universality of those truths. Only then can we distinguish between true and false development.

*Image: John Henry Newman by Richard Woodman, after Sir William Charles Ross, c. 1845 [National Portrait Gallery, London]