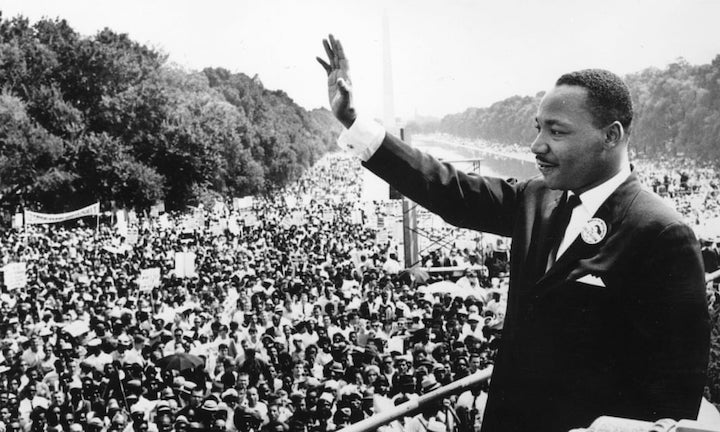

Martin Luther King Jr. delivered his “I have a Dream” speech before a huge crowd at the August 28, 1963 March on Washington, D.C. The key to understanding King’s speech is his appeal to the notion of a “promissory note,” of principles asserted in the “Constitution and the Declaration of Independence.”

Significantly, King was not a proponent of “identity politics,” of black power, because he argued, as the African-American scholar Shelby Steele correctly states, “whites were obligated to morality and democratic principles.” Steele adds that black Americans are obligated “to principles,” not “to black people as a class.”

These principles “ensure the ennobling conditions that free societies aspire to: freedom for the individual, the same rights for all individuals, equality under the law, equality of opportunity, and an inherent right to ‘life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness’.” King sought to dissociate American culture from its “racist past through principle and individual responsibility.”

This is the stuff out of which King’s dream was made. His dream expresses the true meaning of the American creed, King said, appealing to the nation’s moral character, affirming the deep truth about our God-created humanity, which Thomas Jefferson, the architect of the Declaration of Independence, also expressed: “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal and endowed by their Creator with certain inalienable rights.”

Lincoln helped to fulfill the “abstract truth, applicable to all men and all times” asserted by Jefferson, the architect of the Declaration, or the “promissory note,” as King put it. Lincoln fulfilled this note, in principle, with the 1862 Emancipation Proclamation. But it was not, in fact, fully implemented until the 1964 Civil Rights Act.

In this light, we can say that we are not a “systemically” racist society, which is not to deny that there are racists and racism.

Before the Civil Rights Act, King explained, “America has defaulted on this promissory note in so far as her citizens of color are concerned. Instead of honoring this sacred obligation, America has given the Negro people a bad check, a check which has come back marked insufficient funds.” In his speech. King listed the “great trials and tribulations” that black Americans have suffered, namely, statuary segregation, police brutality, lack of opportunity of upward mobility, voting rights suppression, and so forth.

Nevertheless, King refused to believe that “the bank of justice is bankrupt.” He adds, “So we’ve come to cash this check, a check that will give us upon demand the riches of freedom, and the security of justice. . . . Now is the time to make justice a reality for all of God’s children.”

It’s a clear and relevant message to our times, especially in view of the current rioting, looting, destruction of property and businesses, arson, anarchy, and nihilism – and those who are exploiting the brutal murder of George Floyd, not for social justice, as they claim, but really for the destruction of civil society, indeed, of American culture.

By contrast, King eloquently stated:

Let us not seek to satisfy our thirst for freedom by drinking from the cup of bitterness and hatred. We must forever conduct our struggle on the high plain of dignity and discipline. We must not allow our creative protests to degenerate into physical violence. Again and again, we must rise to the majestic heights of meeting physical force with soul force. The marvelous new militancy, which has engulfed the Negro community, must not lead us to a distrust of all white people, for many of our white brothers, as evidenced by their presence here today, have come to realize their destiny is tied up in our destiny. [empasis added]

King did not use race as a battering ram to destroy—as the Black Lives Matter organization holds—the institutions of our society, including the police, the family, the free market system, and cultural documents that are monuments, indeed, noble embodiments of American history.

“I have a dream,” said King that “we will be able to speed up that day when all of God’s children, black men and white men, Jews and gentiles, Protestants and Catholics, will be able to join hand and sing in the words of the old Negro spiritual, Free at last! Free at last! / Thank God Almighty we are free at last.”

What has happened to King’s dream? Several things have obstructed it. First is white guilt, an impotency of moral authority “that comes from simply knowing that one’s race is associated with racism,” explains Shelby Steele in White Guilt: How Black and Whites Together Destroyed the Promise of the Civil Rights Era. Arguably, this is the cause of the kowtowing we currently see all around us in corporate boards, sports teams, politicians, and so forth.

Second, this guilt stems from the charge that white people are socially determined to be racist, irrespective of whether they make choices that can be considered racist. A social determinism regarding race has been raised to the level of “impersonal” and “structural” forces, indeed, to a man’s race – being white – in which he had no hand in bringing about. Thus, institutional racism, or systemic racism, is, Steele explains, a “part of a cultural pattern . . . that automatically oppresses blacks; and blacks are automatically victims of this same pattern.”

If I am a racist by virtue of my whiteness, then this leads to a logical consequence that is absurd, for the only way to eliminate my racism is to eliminate my whiteness. And this is precisely what the city of Seattle proposes to do with classes to “undo whiteness.”

Furthermore, if a black man is a victim by virtue of his blackness, then he cannot be held responsible for anything he does. This encourages black dependence on the welfare state.

Either view contradicts Dr. King’s adage about judging a man by the content of his character and not the color of his skin. Going forward, let’s revive King’s dream. The alternative is something horrible to contemplate.

*Photo (above): Agence France Presse (August 28, 1963)