In a late-November Wall Street Journal column, William Galston noted that anti-Semitism has grown sharply since 2015 in Central and Eastern Europe, once the home of most European Jewry. In Poland, Ukraine, Russia, and Hungary, large numbers of people surveyed believe that Jews have too much power in the business world and financial markets, talk too much about the Shoah, and have too much control over global affairs.

The Holocaust is the single greatest moral catastrophe of the modern West. But its lessons seem too easily forgotten. “The [1948] creation of the state of Israel,” wrote Galston, was the excuse for a new round of “the ancient charge of Jewish disloyalty.” Allegations of disloyalty are today, again, “a pervasive fact of Jewish life” – and not just in Europe. Globally, 38 percent of those polled by the Anti-Defamation League believe Jews are more loyal to Israel than to the nation in which they live.

In Western Europe, Muslim immigration and political influence have compounded the problem. Violence against Jews in France has grown more than 20 percent in recent years, and Britain’s chief rabbi publicly slammed Labour Party leader Jeremy Corbyn for the growing anti-Semitism in his party’s ranks just days before that country’s recent elections. Jew-hatred is not a monopoly of Europe’s populist right. The progressive Left has its own toxic brand of the same poison.

As for the United States: Americans typically rank low in anti-Semitism. But even here, 33 percent of people surveyed believe Jews are more loyal to Israel than to their own country. And hate crimes like the December stabbing attack against Jews celebrating Hanukkah in Monsey, New York, are becoming more common.

Anti-Judaism has a long history in Christian culture. It flows from early, bitter struggles within the Jewish community over the messianic identity of Jesus, and the supersessionist Christian theology that followed in later centuries. But it was Jesus himself – obviously a Jew – who said that “salvation is from the Jews” (Jn 4:19-22), and Christianity makes no sense cut off from its Jewish roots.

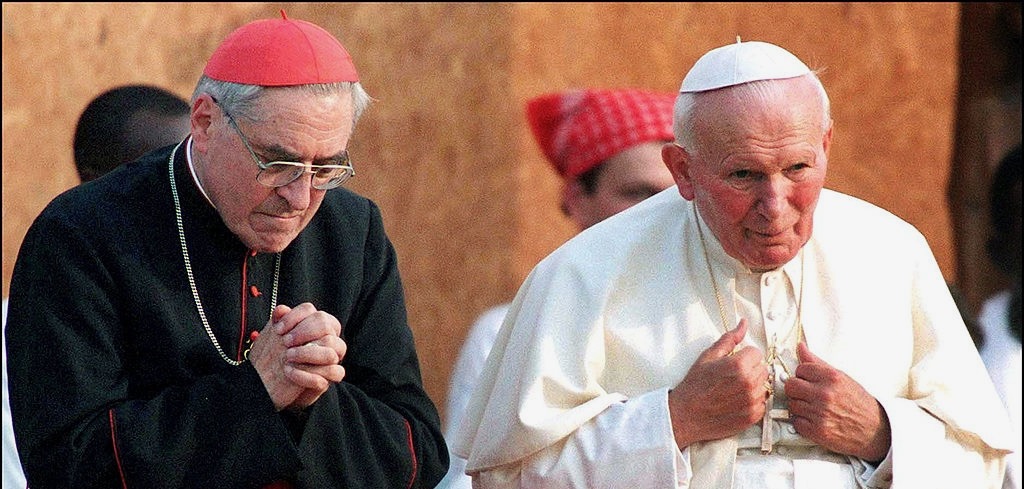

Vatican II sought to reform and restore Catholic relations with the Jewish community through its document Nostra Aetate (“In Our Time”). And as Church statements go, Nostra Aetate was a watershed in Christian-Jewish dialogue, as vitally important today as it was on its release in 1965. But beautiful words and good ideas lack force until they take flesh in a life that proves them true in action. And in that regard, nothing embodied the recovery of Christianity’s Jewish roots more powerfully than the life and work of Aaron Jean-Marie Lustiger.

Lustiger was born in 1926 to a Polish-Jewish immigrant family. His grandfather was a rabbi. His parents ran a hat and drapery shop in Paris. They were largely secular in their home life, but nonetheless carefully sequestered Aaron from French Catholic celebrations and observances. However, the boy, age 10, found a copy of the New Testament on his own, read it secretly, and converted – against the will of his shocked parents – at the age of 14.

He never abandoned his Jewish name. He added the Christian name Jean-Marie at his baptism, but never lost a deep pride in his Jewish identity. He survived the Second World War sheltered by a French Catholic family. His mother died at Auschwitz in 1942 and other members of his extended family were lost in the Shoah. He went on to become a priest; served as chaplain at Paris universities; eventually was named bishop of Orleans, and finally Cardinal Archbishop of Paris.

Lustiger had a vigorous intellect – he was elected to the Academie Francaise in 1995 – immense energy, eccentric tastes in art, a prodigious output of books and talks, and a larger than life personality. To meet and speak with him, as I did on several occasions, was an unforgettable experience, like interviewing an idling locomotive.

He especially treasured the opportunities he had, more often as time went on, to meet with Jewish leaders, audiences, and students. This wasn’t always easy. Jews often see Jewish converts to Christianity as apostates and repudiators of their community. Lustiger respected the sentiment but would not let it deter him from seeking friendships and dialogue partners in the Jewish community. Toward the end of his life, drafting his own epitaph, he summed up his self-understanding when he wrote: “I was born Jewish. I received the name of my grandfather, Aaron. Having become Christian by faith and baptism, I have remained Jewish. As did the Apostles.”

The point of remembering Lustiger, who died in 2007 at the age of 80, is simply this: He understood that for Christians, anti-Semitism/anti-Judaism is not just an evil, but a peculiarly ugly form of blasphemy and self-hatred; a hatred of our own origins and grounding in the God of Israel. Any Catholic seeking to deepen his or her own faith, and to learn the importance of Judaism to Christians through the words of this profoundly Jewish Christian and profoundly Christian Jew, need only read his Choosing God, Chosen by God and The Promise.

As Lustiger never ceased to stress:

One of the tragedies of Christian civilization is that it has become atheistic while claiming to remain Christian. . . [T]he fate reserved for Jews is the test of whether [we] Christianized pagans have truly accepted Christ. It is really the absolute test. This is not simply a matter of the relationship between love of neighbor and love of God. The Jew remains, in a very precise sense, the sign of Election, and hence of Christ. To fail to recognize the Election of the Jews is to fail to recognize the Election of Christ. And it is to be unable to accept one’s own election. The logic is implacable.

The only appropriate response is: Amen.