If things had gone as planned, by this time today, I would be sore and probably hitting the bottle (of Ibuprofen) from having walked fifteen miles, after sleeping on the ground for the past two nights, in a tent. Because – finally – some work that was supposed to take me to Europe around now coincided with this weekend’s annual walking pilgrimage from Notre Dame of Paris to Notre Dame of Chartres.

None of that has happened, of course, because of the virus. A great shame, too, because the Chartres Pilgrimage originated with a man I regard as one of the greatest modern writers – and great Catholic spirits – Charles Péguy.

When Pierre, one of his children, fell sick with typhoid and was near death, Péguy made a vow to the Virgin: if his son recovered, he would make the pilgrimage on foot. Pierre survived; Péguy kept his vow.

It didn’t end there. Péguy died of a bullet through the head at the Battle of the Marne in World War I. He later became famous for his sheer genius and the heroism his works inspired among the French during World War II when the Nazis occupied France. (De Gaulle begins and ends his memoirs quoting Péguy.)

According to good estimates, 10,000 people – many students – had made the pilgrimage by 1960, for reasons of their own. Today, about 20,000 do it, around Pentecost, every year.

Walking pilgrimages are something special, which is why they have appeared almost everywhere, in every age. As Péguy said, the whole question of the soul opens up before you on the road.

Walking is not normally regarded as a spiritual exercise. Many people have learned during this long stretch of undesired lockdown that getting outside, on your own two feet, benefits body and mind.

Good things, to be sure, but in my (sometimes) humble opinion, that risks “medicalizing” walking. And neglecting what could be a much richer experience than the usual modern goals of physical health and emotional tranquility. Because limiting ourselves only to that is where much trouble starts.

Most writing about walking in nature has similar drawbacks. There are some good pages in Wordsworth (avoid Rousseau). But rare is the modern nature writer without a weakness toward pantheism or even full Pachamama.

Which is why we, I’m convinced, have been given other, hallowed examples: Abraham walking from Ur of the Chaldees to the land of Canaan; Moses leading the Israelites out of Egypt to the Promised Land; Jesus himself and his fellow Jews going up, on foot, to Jerusalem at the great feasts; and even the literary pilgrimages like the Divine Comedy and the Canterbury Tales.

I walk the Washington March for Life every year and also, lately, Rome’s Marcia per la vita (also a victim of the virus last weekend). But it’s worth distinguishing a pilgrimage from a march. Marches have their place, an honored place, but they’re primarily about a cause. A walking pilgrimage is about something more fundamental: i.e., the source and reason why we even care about particular causes.

Most causes are worldly matters. As Hadley Arkes never tires of reminding us, for instance, you don’t have to be religious to be pro-life. Protecting all innocent human life – or family and marriage, or religious liberty – is a primary precept for rational beings, religious or not.

And as we’ve seen in the riots over the past few days, without a deep and wide vision of the Good, even protests against clear evils, like racism, can generate evils of their own.

Péguy was right: a pilgrimage fully engages body, mind, and spirit – the threefold division of the human being in the Bible. And it’s a reminder that we’re all on pilgrimage, every day, towards an eternal destiny. Some of us, quite a few these days, just don’t know it.

That’s the modern problem. What else is the aimlessness and lack of purpose in postmodern societies but the lack of a sense that the human story only makes sense, offers any kind of meaning, if ultimately it’s grounded beyond even our greatest worldly concerns? People think radical autonomy is real freedom, until they find themselves at sea, with no rudder or anchor.

Hence the need for something greater.

Many people over centuries have done the pilgrimage to St. James of Compostela, El Camino. I wrote about walking part of it myself a few years ago (here). But there are many other such pilgrim paths, all but unknown except locally. One favorite is St. Cuthbert’s Way, which runs from Melrose in Scotland to the Holy Island of Lindisfarne in the North of England. (See here.) You have to time the last stage just right, because the road there disappears under the sea at high tide, similar to Mont Saint-Michel.

There’s a vast literature on walking. But the greatest modern book on a walking pilgrimage (and much else), without doubt, is Hilaire Belloc’s The Path to Rome. It tells – the result of another vow to the Virgin – of a walk from France, over the Alps, to the Eternal City. In a stunning passage, Belloc describes trying to cross the Alps on foot, and failing: “from the height of Weissenstein I saw, as it were, my religion. I mean, humility, the fear of death, the terror of height and of distance, the glory of God, the infinite potentiality of reception whence springs that divine thirst of the soul; my aspiration also towards completion, and my confidence in the dual destiny.”

Pilgrimages, however, don’t have to cover expanses of countryside. Some do. But that’s only one type. There are urban equivalents – most notably the seven “station” churches in Rome that our friend George Weigel has written about and photographed superbly.

If I were a bishop of a city with a number of interesting Catholic sites, I’d encourage setting up circuits of that kind. Catholics and all of us need to be locally “grounded” – in our hyper-tech age, even more than people in the past. And these should be religious events, not marches; if you want religion in the public square, there’s nothing like bringing it there yourself.

Lots of the world has lost a sense of place staring at pixels on screens. But we’re lacking far more than that. We need to rediscover those questions of the soul that Péguy found opening up on the road, the simple truth that we’re all, every day, on a great pilgrimage.

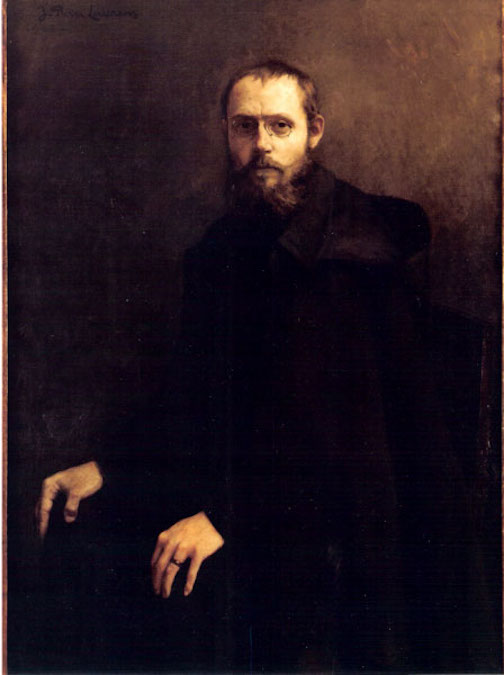

*Image: Portrait of Charles Péguy by Jean-Pierre Laurens, 1908 [Centre Charles Péguy, Orléans, France]