One of the past century’s greatest scientists, Steven Weinberg, died last week amid worldwide acclaim. He wasn’t famous like Einstein or Stephen Hawking, but he probably did more to explain and unify notions about the fundamental constituents of matter and the origins of our universe than any other recent figure. And unlike many scientists, he could write – for technical audiences as well as for general readers. He rightly received a Nobel Prize in 1979. Weinberg stayed active in research and teaching until shortly before he died, a fitting finish for an amazingly productive life – but also a tragic life of cosmic proportions.

His death sent me back to his most famous book: The First Three Minutes. I began university as a physics student. My turn into whatever I am now was, for my father, puzzling. Physics he understood. Liberal studies, he thought, were for rich people who didn’t need to earn a living. At some youthful moments, I almost thought he was right. But in my dotage, I suspect a hidden hand guided me – as it guided Socrates from his early interest in materialist science to philosophy, though with infinitely more modest results. My look back into The First Three Minutes confirms that it was right, for me, to turn elsewhere.

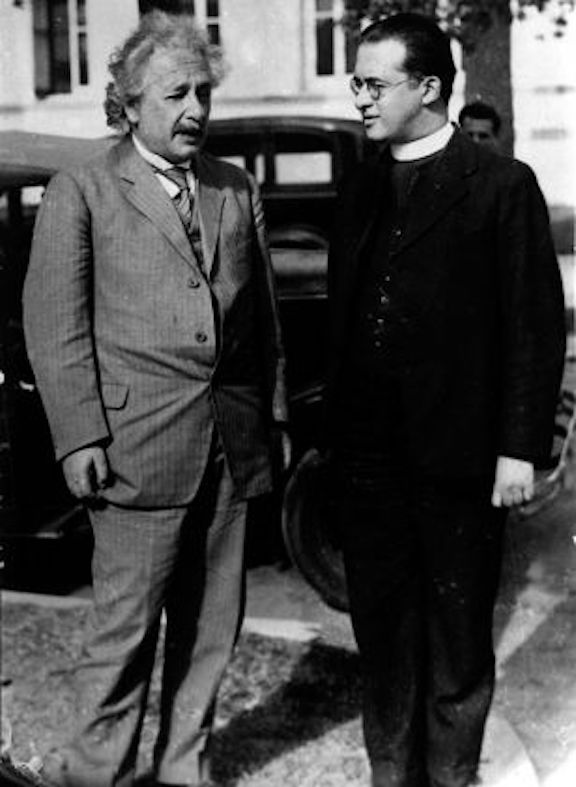

That book, as the title indicates, is a popular account of the beginnings of the universe. (Let us leave aside for the moment how to understand those “minutes” since, as St. Augustine was aware long before Einstein, time itself comes into being with space and, therefore, the nature of time is not easy to specify.) The book is a lively portrayal of the stages scientists believe the universe passed through. From the Big Bang (first postulated in 1927 by the Belgian priest Georges Lemaître) to 10-43 sec. – so-called Planck Time. If you’ve forgotten the math, this means:

1 sec. /10 followed by 43 zeroes

An inconceivably short time.

For that brief space, whatever had come into existence was undifferentiated, or at least we can’t see back further. At 10-37sec. the universe expands faster than the speed of light (impossible now) and material forms with which we are more familiar started to appear. According to Weinberg – the remark was perhaps meant to be humorous – “After that [the first three minutes], nothing of any interest would happen in the history of the universe.”

Or perhaps it wasn’t a joke. He was also famous for saying, “The more the universe seems comprehensible, the more it also seems pointless.” Like many scientists – and an increasing number of ordinary people who know little real science – the approach that modern physics makes to the world, ruling out value questions and almost all relations that cannot be expressed mathematically, which inevitably results in a vision of the universe not as our cosmic home, but as an immense, indifferent, dead, absurd, hostile place – is now the assumed background of our whole society. It’s no wonder so many of our young people say it’s “science” that has turned them into “Nones.”

And that’s the tragedy for Weinberg and us, despite the indisputable genius. I want to ask figures like Weinberg questions such as: but doesn’t the fact that you can know all this mean we are something other than just another physical structure of cells inside our skulls? The day you met the wife you were married to for 68 years, your daughter, her daughter, was all that – and the sun as it rose outside your door every morning – “nothing of any interest”? Is human life just all biology with a thin crust of sociology and psychology on top, all three reducible to chemistry, chemistry to particle physics, the old particle physics itself now reduced to quantum indeterminacy with “spooky,” seemingly illogical effects?

To be clear, I still find all these disciplines quite fascinating, not only in themselves but in the many valuable things they have produced for the relief of our human condition. I’ve even cracked my head (privately) on quantum theories several times in recent years. My main puzzle is not with the science, not even with the modern architecture of the sciences as I just oversimplified them. My quarrel is with the sad, now-old song lacking life, beauty, love, meaning – ultimately God.

Weinberg had the usual disdain for religion, which he pronounced false and an obstacle to seeing the nature of the world. That such an intelligent man would hold on to this ancient myth is disappointing. Weinberg must have known that Fr. Lemaître was hardly the only believer who was also a great scientist – and that the relation between faith and reason is not merely a dispute over Galileo or Darwin. What if the scientific method, proper and productive as it is in its own sphere, is the very thing that for many people prevents them from seeing what might satisfy their deepest desires for meaning, significance, a truth that matters. And where do these urges come from? They make no sense on Darwinian or other materialist theories.

How is it that every known culture has not been content simply to ascribe everything to physical forces that – they as we – of course know exist? What is it that makes us, even makes Steven Weinberg, look out there? He’s like a teenage mechanic trying to understand more and more of how the car’s engine runs while everyone else is going out Saturday night.

And what keeps such a person at this mournful task?

Existence – especially life – is too mysterious, strange, wonderful, to limit it to what our brains can determine about the physical world. (For a wiser perspective, try physicist Stephen Barr’s Modern Physics and Ancient Faith.) We’ve confused for far too long conceptual genius with human wisdom. Even with goodness. It’s right that we continue to carry out that very human thing, the scientific enterprise. But there’s another kind of science, even though we mostly ignore it. It’s what makes everything after those first three minutes not only “of interest,” but infinitely intriguing.