As even the military leaders of the disastrous withdrawal from Afghanistan are admitting their failures and after so much else has gone wrong in that perpetually troubled nation, it’s good to remember that, in its own quiet way, the Church has been at work and had a significant presence there. Various Catholic agencies have been helping the Afghanis in recent years, but one, in particular, deserves some attention.

This is how Barnabite Father Giovanni Scalese, superior of the missio sui iuris in Afghanistan, and the only Catholic priest in Afghanistan, announced his return to Italy after the American withdrawal:

I arrived this afternoon at Fiumicino airport with five sisters and fourteen disabled children, whom the sisters were taking care of in Kabul. We thank the Lord for the success of the operation. I thank you all that these days have raised to Him incessant prayers for us, prayers, which, evidently have been answered. Continue to pray for Afghanistan and for its people!

Accompanying Fr. Scalese were four Missionaries of Charity, Mother Teresa’s order, who had served in Afghanistan since 2006, and a Pakistani Sister, Bhatti St. Shahnaz, of the Congregation of Saint Jeanne-Antide Thouret. Sister Shahnaz ran a facility for children with mental disabilities established by the association Pro Bambini of Kabul. Unfortunately, those children were unable to escape. Fr. Scalese’s return to Italy marked the end of the 88-year-old Barnabite Afghan mission.

What were the results of this mission? Was anything “accomplished” The only Catholic missionaries in the country were forced to flee and the prospects for their return are dim. But the Church has faced seemingly impossible odds since it first appeared in the mighty Roman Empire. And God has His own ways.

So, a little history is in order – and hope for the future. In 1921, Italy became the first Western country to recognize and establish diplomatic relations with Afghanistan. They agreed to exchange permanent diplomatic missions, and to the possibility of hosting a Catholic chaplain within the Italian embassy. At the time, Afghan King Amanullah was receptive to requests from foreigners living in Afghanistan for spiritual assistance.

A year later, he turned to the Italian government – probably the first time that a king ruling a majority Muslim country requested a Catholic chaplain to meet the spiritual needs of Christian foreigners. There were two conditions. No proselytism of the Muslim population. And the Catholic chapel was to be erected within the Italian embassy (no Christian church could legally be erected on Muslim soil).

The Italian government turned to Pope Pius XI, who said: “A Barnabite is needed here [Kabul].” He chose the Clerics Regular of St. Paul, commonly known as the Barnabites, who include priests, religious women, and lay people – especially married couples.

The order, founded in 1530, draws inspiration from St. Paul. Fr. Egidio Caspani was Pius XI’s choice to start the mission. A second Barnabite, Fr. Ernesto Cagnacci, joined Fr. Caspani as a priest/official of the Italian embassy. The first Catholic Mass was celebrated there on January 1, 1933, the official beginning of the mission.

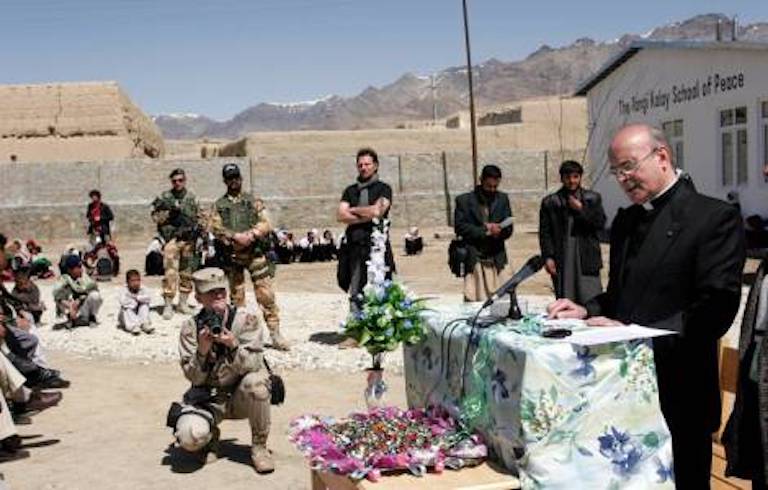

In 2002, Pope John Paul II elevated the Kabul Christian mission to a Missio sui iuris – an independent mission under the direct jurisdiction of the Church. Consequently, the mission and the church became official Christian presences in a Muslim country. The church, of course, did not have local faithful and local clergy, but with time, the mission and its clergy became part of the reconstruction of Afghanistan. The Barnabite Fr. Giuseppe Moretti in 2005 helped establish the Tangi-Kalay School of Peace, a school that received both state support and private donations.

The Barnabite mission to Afghanistan operated on the model of St. Paul’s Mission in Malta. (Acts 28, 1-10) His was a mission of presence, exchange, and gratitude. Paul’s presence and service to the islanders were Christ-like: Christ came to serve, not to be served – and Paul was imitating the Master. The Barnabite witness in Afghanistan was a witness to God: they were Catholic priests who became parish priests par excellence for the entirety of Kabul, and before the recent pull-out had been an almost a century-old presence among the Afghan people.

We’ve had saintly examples of such witness among Muslims before, and the results may someday surprise us. For example, Blessed Charles de Foucauld with his mystical imitation of Christ among North African Muslims resembles the Barnabite mission in Afghanistan. Foucauld’s life and death were a religious-prophetic witness. Similarly, for the Barnabites and other Christian missionaries, their lives in Afghanistan were a combination of prophecy, presence, and dialogue. The missionaries opted to live the hidden life of Jesus among the Muslim Afghanis.

Such efforts may seem, by human standards, meager. But instead of judging as the world judges, we would do well to pay attention to the words of St. John Henry Newman that authentic Christian prophets and mystics are those individuals who “live in a way least thought of by others, the way chosen by Jesus of Nazareth, to make headway against all the power and wisdom of the world. . . .They take everything in good part which happens to them and make the best of everything.”

The Barnabites did not go to Afghanistan to convert and proselytize the local Muslim population and openly proclaim the Gospel – conditions did not make that a possibility. But according to reliable reports, there is now a modest contingent of Afghanis who converted from Islam and practice their Christian faith in secret. As in other Muslim countries, these converts may be hidden now, but may lead to a surprising future.

Can we speak of the Barnabite Mission to the Afghanis as “Mission Accomplished”? No, not in the ordinary sense of the words. But is there hope for the mission’s future in Afghanistan? Afghanistan at present is in chaos. In Kabul, the witness the Barnabites have given has planted seeds that may lead to surprising growth in God’s good time among future generations of Afghanis.

You may also enjoy:

Michele McAloon’s A Christian Response to Defeat

Matthew Hanley’s The Strange Feminist Silence on Islam