On June 29 (the Feast of Sts. Peter and Paul), Pope Francis circulated another liturgical directive, Desiderio desideravi, a kind of companion piece to Traditionis custodes, his motu proprio of last year that regulates the celebration of the Tridentine Mass. Both texts ordered and argued for strict limitations on the celebration of the preconciliar rite, i.e. prior to Vatican Council II (1962-1965).

In Traditionis, Francis asserted that the preconciliar rite had become a banner for Catholics who rejected the Council and cited a survey of Catholic bishops as evidence. Several Catholic commentators have defended Francis’s claim. They find the popularity of the old rite among young Catholics especially disturbing – almost unfathomable.

Much of the debate about the preconciliar rite maintains that the Novus ordo, the rite that the vast majority of Catholics attend today, represents the intention of Vatican II. The council’s blueprint for reform, however, the constitution Sacrosanctum concilium, suggests that the adherents of the preconciliar rite may be more faithful to the liturgical vision of Vatican II than their detractors.

Pope Paul VI promulgated Sacrosanctum concilium (hereafter SC) on December 4, 1963, which was six years prior to the establishment of the Novus ordo. SC called for greater lay participation in the liturgy, meaning that the laity should recite Mass parts along with the clergy: “To promote active participation, the people should be encouraged to take part by means of acclamations, responses, psalmody, antiphons, and songs.” [30]

Instead of an epistle and a Gospel, as in the preconciliar Mass, the reformed liturgy should have “more reading from Holy Scripture, and it is to be more varied,” i.e., from the Old Testament, rarely found in the earlier liturgy, and more of the liturgy should be in the vernacular, a decision to be made by “the competent territorial ecclesiastical authority,” namely, “territorial bodies of bishops.”

But the council also clearly stated: “The use of the Latin language is to be preserved in the Latin rites.” [36.1] The introduction to the Constitution stated that “the rites be revised carefully in the light of sound tradition” [4], for “there must be no innovations unless the good of the Church genuinely and certainly requires them,” and they should “grow organically from forms already existing.” [23]

Further, SC orders that “steps should be taken so that the faithful may also be able to say or to sing together in Latin those parts of the Ordinary of the Mass which pertain to them.” [54] Steps like these had been taken for centuries; medieval councils decreed that parents ought to teach their children the Lord’s Prayer in Latin. After the advent of printing, missals had Latin and vernacular on facing pages.

SC approached other possible reforms in much the same way. While other musical forms might fit liturgical purposes, “the Church acknowledges Gregorian chant as specially suited to the Roman liturgy: therefore, other things being equal, it should be given pride of place in liturgical services.” [116]

A new edition of books of Gregorian chant should be edited [120], in accord “with the most rigorous scholarly methods.” [117] And the organ should continue to be the primary musical instrument played during the Mass, “for it is the traditional musical instrument which adds a wonderful splendor to the Church’s ceremonies and powerfully lifts up man’s mind to God and to higher things.” [120].

SC mentioned nothing about ad orientem or versus populum, or the priest’s vestments.

SC’s vision vanished in the liturgical reform wrought between its promulgation and the implementation of the Novus ordo in 1970. Latin yielded entirely to the vernacular. Gregorian chant virtually disappeared, and the organ took a back pew to guitar, drums, and tambourine. Much was edited out; a few, long-abandoned prayers (e.g., the Prayer of the Faithful) were reinserted.

These alterations confounded a number of learned prelates who had been Council Fathers. Cardinal Josef Frings, a distinguished medieval scholar and the archbishop of Cologne said in 1969: “This is not what we council fathers decided; this is against the decisions of the council. I cannot understand how the Holy Father could give his consent to such a thing.”

In his view, “the council didn’t want many things, but then came the periti (experts), and they were mostly very progressive gentlemen, and they pushed everything in a different direction.”

Cardinal Alfons Stickler, an influential ecclesiologist, rendered a similar judgment: “You can understand my astonishment when, on taking note of the final addition of the new Missale Romanum, I found that its contents in many respects did not correspond to the texts of the council with which I was well-acquainted, much was altered, expanded, and even directly contrary to the decrees of the council.”

Bishop Robert J. Dwyer of Portland, Oregon, lamented:

Who could have dreamed on the day Sacrosanctum concilium was promulgated that in a few years, in less than a decade, the Latin tradition of the church would be all but extinguished and become a slowly fading memory? The thought of this would have horrified us, but it seemed so inconceivable that we considered it ridiculous. And so we laughed it off [when a Sicilian bishop predicted precisely what happened while the council was still meeting].

Frings’s peritus, Josef Ratzinger, wrote to a colleague in 1976: “I can say with certainty from my knowledge of the council debate and from rereading the speeches of the council fathers delivered at that time that [the Novus ordo] was not intended by them.”

The Jesuit musicologist Joseph Gelineau added: “the Roman rite as we knew it no longer exists.”

According to these authorities, the preconciliar rite was closer to the liturgical vision of Vatican II; the rite finally implemented in 1970 departed from it in general and in detail.

So how can anyone claim that the small number of Catholics who worship in the Mass of St Pius V reject a Council that decreed that their liturgical preferences mostly be preserved?

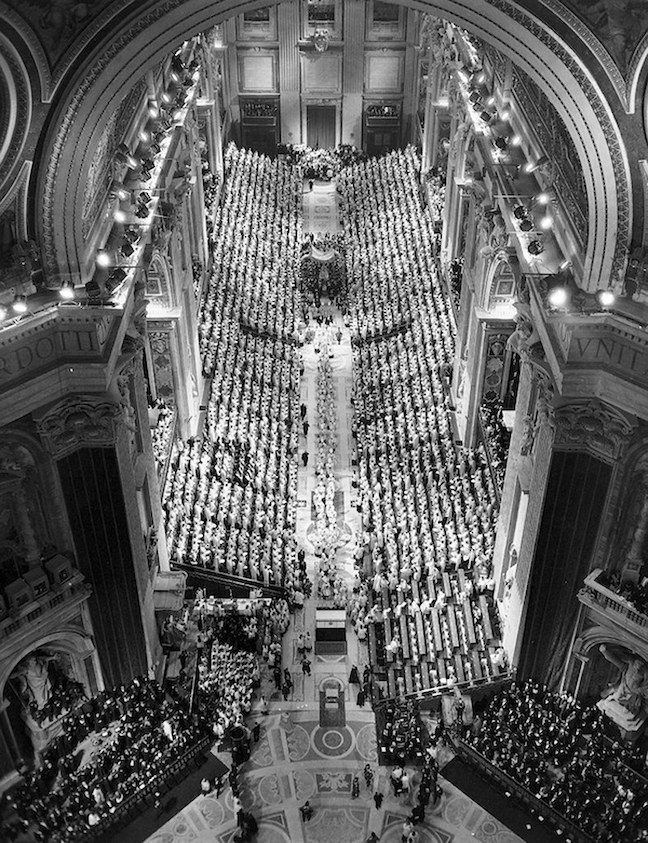

*Image: Pope John XXIII opens the Second Vatican Council, St. Peter’s Basilica, October 11, 1962 [L’Osservatore Romano photo]