Today is the Feast of St. Augustine – and also my late mother’s birthday. I don’t think she ever read a word of Augustine’s, but she may have caught wind of St. Monica’s tears over her young son (as recounted in Confessions) . . . and made the connection to her own son’s adolescent waverings. In any case, when you read Augustine, it’s almost impossible not to see parallels with your own life, and in a deeply personal way. Aquinas is primarily the great master of the mind, Augustine the passionate guide to the heart.

The very first page of Confessions, of course, contains his much-quoted line: fecisti nos ad te et inquietem est cor nostrum donec requiescat in te (“You made us for Yourself, and our hearts are restless until they rest in You.”) You can read that as simply a pious expression, and no harm. (When I teach Augustine, though, I warn students not to assume they already know what “heart” signifies here.) If you read on, you get a profound exposition – amidst a story of worldly temptations and ambitions, intellectual and spiritual confusions, as powerful then as they are now – of what those seemingly simple words mean.

Social commentators sometimes talk about how “the world has lost its story,” meaning we no longer know why we exist as persons or societies. At bottom, the story we’ve lost is the Biblical view of history. As a result, the stories we substituted for it – enlightenment, national greatness, economic progress, even science – which depended on there being a sense and direction to life, no longer have any real substance.

And it shows. Desperate attempts at establishing “identity” by latching on to race and gender “communities,” or engaging in environmental or political crusades, are in the end, modern manifestations of unquiet hearts.

In a way, even a massive work like City of God, written to refute the charge that Rome’s abandoning of the pagan gods for Christianity led to its sacking in 410 by the Visigoths, reflects Augustine’s belief that our confidence in our own powers, independent of God, to establish perfect justice on earth is just another delusion we hope will quiet our restlessness.

Augustine’s Confessions first narrates what it’s like to lose the world’s true story and flail around. He weaves much philosophy and theology – and astute psychology – into the drama of his own life and conversion, which involved some of the great figures of his time – prominent philosophers, religious leaders, politicians, St. Ambrose, even the Roman emperor, many friends and ordinary folk.

But his personal story finally makes sense only when he recovers the larger story, a natural subject for fiction writers. Louis de Wohl, half a century ago, wrote a still-interesting novel about Augustine, The Restless Flame. And the young Augustine’s concubine, unnamed in Confessions, has received imaginative treatment in Suzanne Wolfe’s The Confessions of X.

Fr. Aidan Nichols O. P., with a humility rare among great scholars, bluntly admits, “With the possible exception of Cicero, more is known about Saint Augustine than about any other figure from Antiquity. We know far too much about him for that knowledge to be readily manageable.”

Yet Nichols, in The Singing Masters: Church Fathers from Greek East and Latin West, manages marvelously. (In our own modest way at TCT Courses, we’ve tried to give you manageable introductions to Confessions and City of God.)

Still, what’s to be learned from a man who died 1600 years ago, in a time and place so different from our own that it takes a serious effort – of imagination as well as study – just to begin to understand what he was all about?

Well, perhaps the first thing is that despite all those differences there’s much that speaks, with sharp immediacy, to us because – pace the proud progressives of all ages – many human things don’t change.

Fr. Nichols sums it up as a tale of “two trees.”

The first, the pear tree that Augustine and his teenage posse stole fruit from, early in Confessions, not because they were hungry, or the pears were good (they weren’t), but out of casual perversity. The deepest refutation of what we now call being “woke” is the classical and Christian belief that human hearts, all human hearts including the most “woke,” waver between good and – to use the tight term – evil.

In the ancient world, people were so aware of evil that a religion developed – Manichaesim – that posited two gods, one good and one evil. Augustine spent around a decade embroiled in this false faith until he thought his way through – and out. But many others did not. Fr. Nichols says, “The fullest set of Manichee writings are in Chinese, testifying that the ‘Religion of Light’ spread quite as far eastward as it did westward. From Algeria to China, it was Christianity’s main competitor until the rise of Islam.”

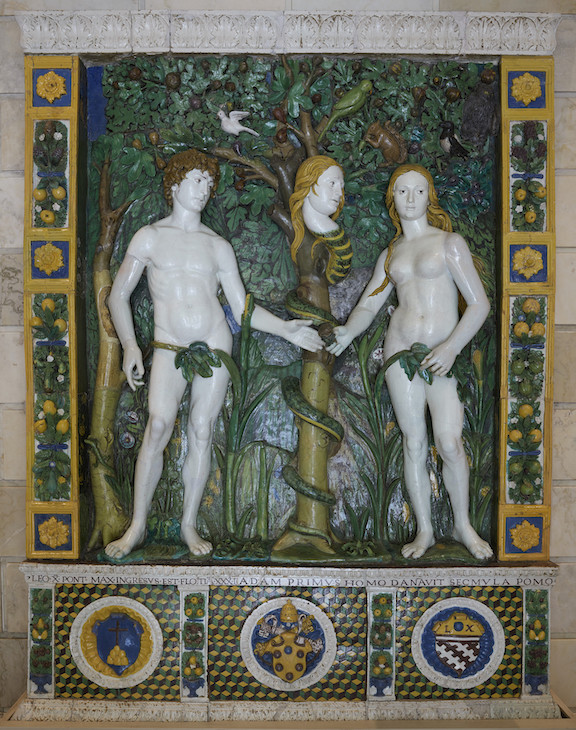

The pear tree, like the tree of the knowledge of Good and Evil, tells a deep story. Ultimately, it isn’t society, or economic conditions, or your family that explain your bad behavior, because any imperfections to be found among them stem from the same human source: restless hearts attracted to good and evil.

But there’s another tree in the story. At the moment of his conversion, “I flung myself down, how, I know not, under a certain fig-tree,” says Augustine. (Bk. VIII) Fr. Nichols notices what many of us might overlook: that the second tree is a fig tree, and it was from fig leaves that Adam and Eve fashioned themselves coverings after they sinned and felt naked.

Augustine no doubt had this in mind. And so what’s about to happen is precisely a reversal of the direction that we took that fatal day in Eden.

Which happens every time someone is converted – turns in the right direction, recovers the world’s story, which is also our own personal story, and finds peace of heart.

__________