The single most iconic moment in late ‘90s cinema is arguably Neo’s choice in the first Matrix film. The Matrix, for those with a leaky memory, posits a future where humans live in an envelope of illusions; a dreamworld of everyday normalcy. In reality, each floats in a narcotic bath managed by sentient machines. Humans created the machines and gave them intelligence. The machines then enslaved the humans. They now use their living, anesthetized human creators as battery power.

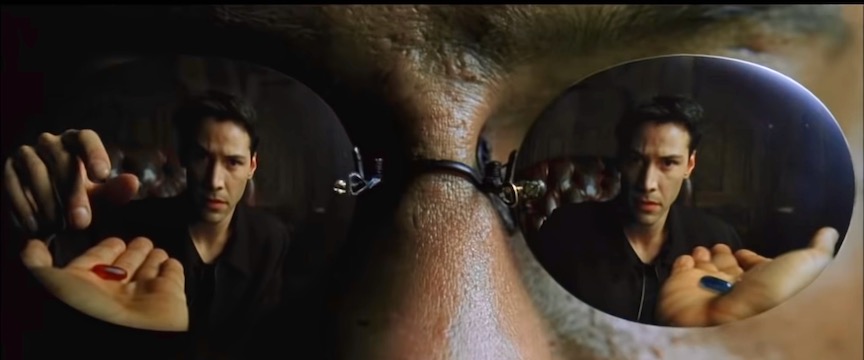

The storyline is simple. Neo (an anagram for the “One”) is a computer programmer and hacker. He senses that something indefinable is wrong with the fabric of everyday life. He’s contacted online by members of the human underground working to overthrow the machines. They present him with a choice of two pills. The blue pill will return him, untroubled, to the pleasures of his dreamlife. The red one will open his eyes to sobering reality. Neo takes the red one and frees his mind. He goes on to become, in effect, humanity’s savior.

Written and directed by the Wachowski Brothers (now the Wachowski Sisters, thanks to the “miracle” of genderbending drugs and surgery) the film is a mishmash of imaginative genius, Biblical messianism, and ersatz Eastern mysticism. It captures perfectly the cost of man’s playing at Sorcerer’s Apprentice; the price of overestimating our wisdom and underestimating the consequences of our tools.

What we call progress always comes with strings. If technology giveth, it also taketh away. Writing records our thoughts, but as Plato argued, it also weakens the memory. The automobile transports us quickly, but also pollutes the atmosphere. So it is with every new technology.

And in the world of The Matrix, the new tools take everything, starting with human freedom and dignity. The machines literally feed on the lives and energy of their deluded victims, exactly as pagan idols, themselves empty, drew their lives vampirically from their worshippers.

Of course, The Matrix is science fiction. It’s just a story and very far from the world we have here and now. But maybe not so far as we’d like to think. Consider the following, written barely two years ago:

Sometimes I lie awake at night, or I wander in the field behind my house, or I walk down the street in our local town and think I can see it all around me: the grid. The veins and sinews of the Machine that surrounds us and pins us and provides for us and defines us now. I imagine a kind of network of shining lines in the air, glowing like a dewed spiderweb in the morning sun. I imagine the cables and the satellite links, the films and the words and the records and the opinions, the nodes and the data centres that track and record the details of my life. I imagine the mesh created by the bank transactions and the shopping trips, the passport applications and the text messages sent. I see this thing, whatever it is, being constructed, or constructing itself around me, I see it rising and tightening its grip, and I see that none of us can stop it from evolving into whatever it is becoming.

I see the Machine, humming gently to itself as it binds us with its offerings, as it dangles its promises before us and slowly, slowly, slowly reels us in. I think of the part of it we interact with daily, the glowing white interface through which we volunteer every detail of our lives in exchange for information or pleasure or stories told by global entertainment corporations who commodify our culture and sell it back to us. I think of the words we use to describe this interface, which we carry with us in our pockets wherever we go, as we are tracked down every street and into every forest that remains: the web; the net.

I think: These are things designed to trap prey.

That passage comes from an extraordinary series of essays, The Tale of the Machine, by the British writer and recent convert to (Orthodox) Christianity, Paul Kingsnorth. The specific essay quoted is “You Are Harvest,” published in October 2021. It makes important reading, as does the entire series. His Substack site, The Abbey of Misrule, ranks with N.S. Lyons’s The Upheaval and Matthew B. Crawford’s Archedelia, as some of today’s finest cultural commentary available anywhere.

And if we’re tempted to think of Kingsnorth as alarmist or excessive, we need to think again. Jacques Ellul, the great French Protestant philosopher and theologian, said the same and even more in The Technological Society nearly 70 years ago.

Ellul argued that the modern addiction to technology-as-panacea inevitably “causes the state to become totalitarian, to absorb the citizens’ lives completely. Even when the state is liberal and democratic, it cannot do otherwise than become totalitarian. It becomes so directly or, as in the United States, through intermediate persons. But despite differences, all such systems come ultimately to the same result.” The average American teen now spends up to nine hours a day staring at screens. That has psychological, and therefore social, and thus political, consequences.

In The Matrix, Neo’s awakening to reality involves literally unplugging from the machines and a painful, if salvific, recovery. Paul Kingsnorth has stripped away as much of today’s high-tech, narcotic cocoon as he can from his family’s daily life. (He still writes on his computer; he’s not crazy.)

And he’s happier for it – for good reason. We can’t be the creatures of dignity God made us to be; we can’t be leaven in the world; we can’t serve Jesus Christ and see clearly what needs to be done in the world, if we’re lumps of its sleeping debris. We’re meant to be better than that. As St. Paul writes, we’re meant to be sons and daughters of the light, so “let us not sleep, as others do, but let us keep awake and be sober.” (1 Thess 5:6)

In other words: Take the red pill.

__________