The wonderful thing about a genuine emergency is that it makes plain what must be done. There is no controversy, we might say. A catastrophe can only be avoided if we: run, hide, pay, shoot, or whatever is “indicated” (as a lawyer might say) by the event itself.

What we must do is clear, within the panic induced by a real emergency – and we may even have the power to do what would not come naturally at any other time. (God arranged this in His plan for us, it seems to me.)

There is no time to debate, and wouldn’t be even if there was something to debate, when circumstances “go critical.” If you don’t take the “indicated” action, it will be all over for you. Not, “may be over for you”; true emergencies are conclusive.

Or maybe it will be all over, no matter what action you take. In that case, no action is indicated. As a veteran idler, I have long argued the case for “no action, in politics and elsewhere through the theater of the world. Calm, rather.

This almost always works, in retrospect; more’s the pity it is seldom tried. It works even when it catastrophically fails.

But it is a hard sell. The idea that, “Something must be done!” wins most elections, and inspires most unelected leaders. It has most frequently prevailed since before historical records were collected.

By comparison, doing nothing smacks of laziness; or will be criticized as lazy, which comes, usually, to the same thing.

Inaction, triumphantly supported in much of the world’s more thoughtful literature, and most religious doctrine, is not always the result of laziness, however. It usually requires a greater risk. It is often, instead, the result of a mature calculation: that nothing we can do will make things better, and could very easily make things worse.

Take inflation, as a topical example. Price stability, overall and over time, requires an extraordinary degree of inaction. But it can be done and, for instance, was in England, where penny and shilling remained constant for centuries, in the Middle Ages. No one had done anything interesting at the exchequer for a long time, and the bankers had been sleeping.

It took Henry VIII, known to Catholics for other reasons, to shake things up. The currency promptly lost half of its value in the Henrician “reforms.” He wanted extra cash to conduct his wars (with France and Scotland).

“The Great Debasement” was Henry Tudor’s clever tactic. He had already taxed his people beyond their willingness or ability to pay, but by doing things like inserting copper in gold, or tin in silver, a whole new economy was created – one which caused the ruin of many.

Henry succeeded, as he usually did. He could mint so much more coinage by mixing in base metals, and he could force people to accept it by law. The only problem: it was becoming worthless.

I mention this one instance only, from economic history, because it is typical of all things politicians (including churchmen when they act as politicians) do. It is the currency that is being devalued, sometimes; but at other times it is other things.

For instance, moral degradation does not necessarily require collapsing the currency. There are a thousand ways to make life cheaper and more frightening, just by relaxing the criminal laws.

Are all politicians evil? I wouldn’t want to estimate the proportion, but as Lord Acton observed, “Power tends to corrupt, and absolute power corrupts absolutely.”

He continued, in the same letter to Lord Creighton: “Great men are almost always bad men, even when they exercise influence and not authority, still more when you superadd the tendency or the certainty of corruption by authority. There is no worse heresy than that the office sanctifies the holder of it.”

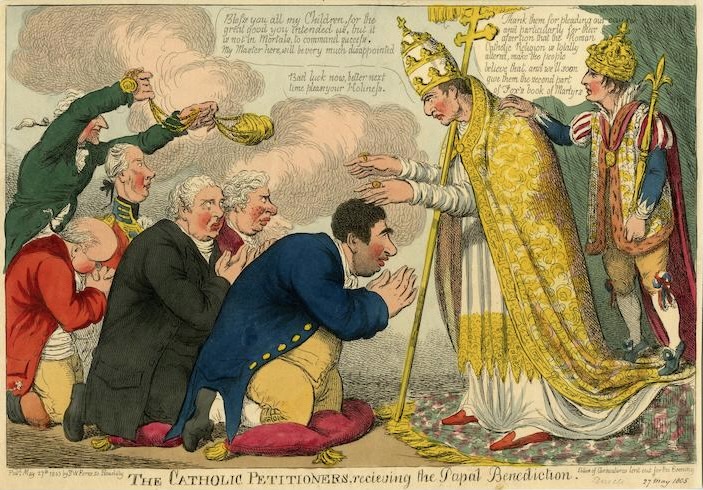

Alas, this would apply to popes as well as presidents; but Acton uses examples from our English-speaking past, to condemn the great and powerful.

“I would hang them higher than Haman, for reasons of quite obvious justice, still more, still higher for the sake of historical science.”

The passages, to be found in Acton’s Historical Essays and Studies, are an exhilarating confutation of the notion that the writer accepted facile excuses, or that he could be scientifically non-judgmental.

His own tendency was to look at things as they are, and from his Catholic training to see morals absolutely.

This superb historian’s “advice to persons about to write history” was – “Don’t.” And this because of temptations from Country, Class, Church, College, Party, Authority, and the solicitation of friends.

Indeed, the many other canons or apothegms attached as a postscript to that deservedly famous letter constitute a moral education for those who seek power; and who, seeking power, have already embarked on a course of corruption.

Power, and all “good ideas,” unchecked by random events, lead invariably to catastrophe. Against this, the choice is to take nothing, except the most obvious and immediate steps; and to fall back on Faith.

“Faith must be sincere, when defended by sin it is not sincere; theologically, it is not Faith.”

Similarly, “God’s grace does not operate by sin. Transpose the nominative and the accusative, and see how things look then.”

I was reviewing such precepts in the company of Bill Clinton, and Jorge Bergoglio, speaking to each other digitally, as it were; and in anticipation of the Synod on Synodality that comes now that summer is ending.

Many points have been raised by others and could be raised by me against the various religious, environmental, and pure power-political measures that are floated in the stream of air. Emergencies are cited as conventions of fact (the same old, boring emergencies), and they are being planned for.

As a Catholic, I expect to be scandalized by what will be done; especially by those measures which are “new.” But I am tired of being scandalized.

__________