In the first few centuries of the Christian era, there was a widespread belief – perhaps I should say, feeling – in the Roman Empire that there was something fundamentally wrong with the world (by “world” I mean “universe”). For many, the practical implication of this belief was that we should adopt an attitude of rejection of the world. Accordingly, a number of popular religions of the time were world-rejecting religions – for example, Mithraism, Manicheism, and other varieties of Gnosticism.

This spirit of world rejection was also common among Christians. Hence the rise of Christian monasticism with its rejection of the secular world, wealth and power, and marriage and family; its rejection of the pleasures of bed and table, its deliberate embrace of a life of full-time prayer and mortification of the flesh.

But Christians, although they embraced an asceticism very similar to the asceticism of the world-rejecting religions that were in competition with their own religion, were unable to embrace the theory upon which this alternative asceticism was based. That is, Christians were unable to view the physical universe as fundamentally evil.

True, they were able to view it as badly damaged due to the sin of Adam and Eve – but not as fundamentally evil, evil from its moment of creation. For Christianity, which included the Old Testament as an essential part of its teaching, held that the world was good at its beginning. After the six days of creation, God looked at his product and saw that it was not merely good but “very good.”

But its goodness was soon marred. Adam and Eve sinned, and as a result a multitude of evils were let loose in the world. This Genesis story bears a striking resemblance to the Greek myth of Pandora, who, when she opened the forbidden box, let loose countless evils. Afterwards, only one thing remained in her box: hope. Likewise, after the sin of our first parents, there remained the promise of a redeemer.

The opening paragraph in Pope Pius XI’s 1937 encyclical denouncing Communism (Divini Redemptoris) eloquently summarizes this Christian story:

The promise of a Redeemer brightens the first page of the history of mankind, and the confident hope aroused by this promise softened the keen regret for a paradise that had been lost. It was this hope that accompanied the human race on its weary journey, until “in the fullness of time” the expected Savior came to begin a new universal civilization, far superior even to that which up to this time had been laboriously achieved by certain more privileged nations.

If the world was a damaged world, not an intrinsically evil world, it followed that it could be repaired, and so Christ, the Divine Repairman (so to speak), eventually arrived. But if Jesus was the model for Christians, then it also followed that Christians should assist him in this repair work. They should make this sorry world a better place.

And so they did. They did this through love of neighbor. They did it by practicing the corporal and spiritual works of mercy; and if many of these Christians didn’t personally do much in the way of works of mercy, they contributed to a cultural spirit of mercy by admiring and applauding those who devoted their lives to these works. It was these ancient and medieval Christians – more specifically Catholics – who laid the foundations of our marvelous modern systems of education, law, and medicine. They, while not always peaceful themselves, created the as-yet-unattained ideal of world peace.

And so Christianity – again more specifically Catholicism – was not simply, like Mithraism and Manicheism and Gnosticism, a world-rejecting religion; it was also a world-improving religion.

But it was both of these at the same time. And there was a tension between the two, almost a contradiction. If it had been purely world-rejecting, why should it care about improving the world? And if it had been purely world-improving, why would it bother to promote monasticism?

But Catholicism is a religion strongly marked with beliefs that are close to being self-contradictory: for example, a monotheistic God who gives the appearance of being tri-theistic; a savior who is both man and God; a virgin who gives birth; a crucified man who comes back to life. If there is an apparent contradiction between world rejection and world improvement, this is very much in accord with the spirit of Catholicism. We make the most of it; we let this near-contradiction breed creativity. And so it did for many centuries.

In recent centuries a new kind of worldview has emerged that is quite the opposite of world-rejection-ism. It is a purely secular worldview. When it is most consistent, it is an atheistic worldview. Sometimes it manifests itself in a moderate form; for example, Benthamism (Utilitarianism). Sometimes in a more radical form; for instance, Marxism-Leninism.

In America today, this atheistic worldview manifests itself in what I like to call (when I talk to myself) neo-Benthamism. By its adherents, it’s usually called Progressivism. The benevolent aim of the progressives is to – gradually but steadily – improve the world (“make the world a better place” is the way they like to put it) until all the inhabitants of this planet live in peace and security and prosperity and personal freedom and happiness.

This secular worldview has invaded American Christianity and deeply corrupted it, persuading tens of millions of American Protestants and Catholics that theirs is a purely world-improving religion, not at all a world-rejecting religion. In other words, it is a religion of neo-Benthamism clothed (disguised) in the rhetoric of Christianity.

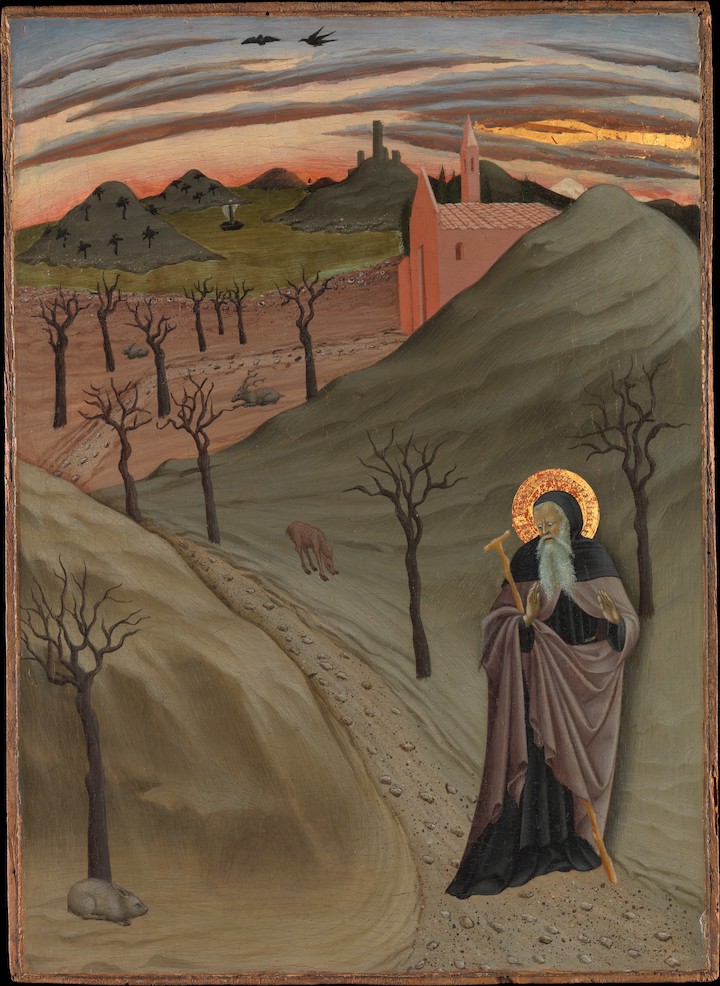

I have no crystal ball, but it is my personal belief that Catholicism will not return to its true nature until it recovers its world-rejection element. That is, its strongly ascetic element. We are in desperate need of a return to monasticism. We are waiting not only for a new St. Benedict (as Alasdair MacIntyre has memorably inserted into modern Christian discourse), but a new St. Anthony of the Desert.

__________