Does Eucharistic consecration help us understand transgenderism? The renowned atheist Richard Dawkins thinks so. In an interview with fellow atheist Peter Boghossian, Dawkins made this provocative comparison:

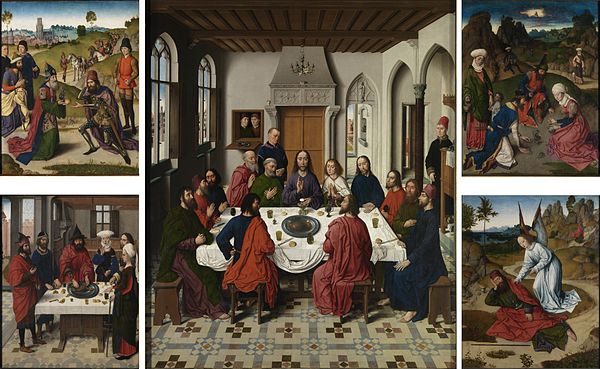

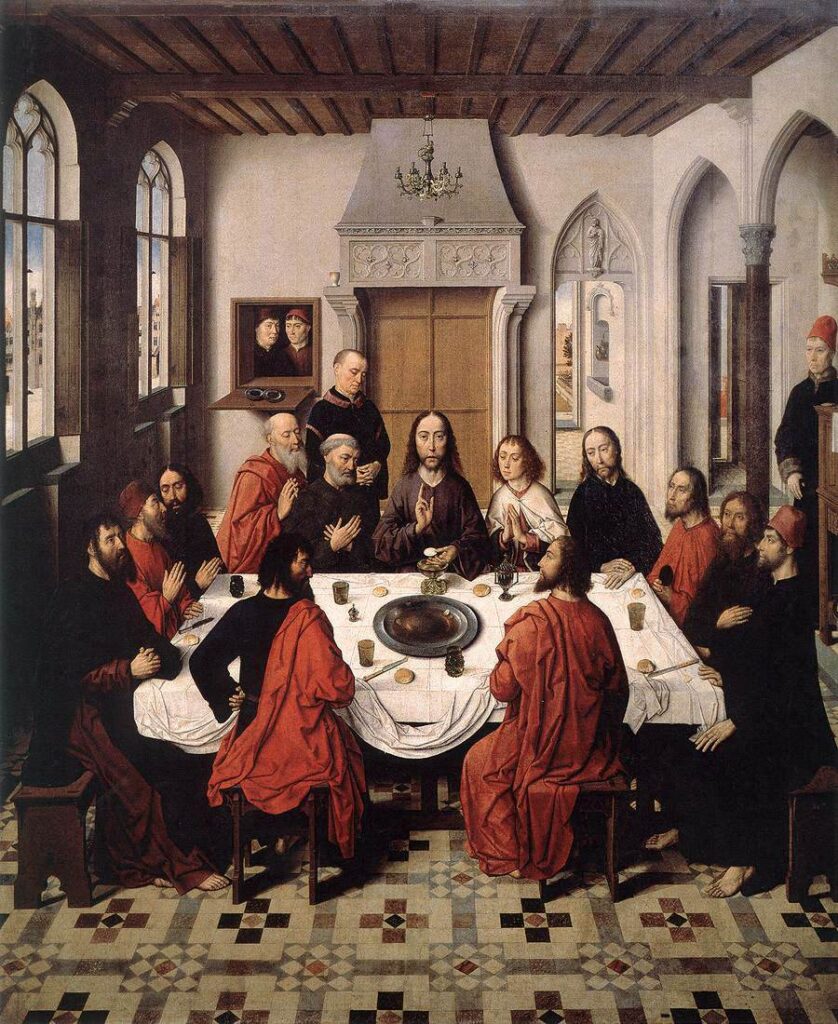

There’s a very strong analogy to transubstantiation in transexualism. . . .The wine becomes blood when the priest simply declares that it is. And a male person becomes female when he declares himself to be female. And in the Aristotelian terms the substance has changed – the substance of wine has changed to blood; the substance of maleness has changed to femaleness. But the accidentals, the incidentals, are what are regarded by Catholics as trivial and by trans people as trivial, so they really believe that they have become the other sex.

This analogy doesn’t just limp; it has things backwards. In Eucharistic consecration, the essence is changed, while the appearances remain. What still tastes and smells like wine is in fact no longer wine. It is entirely the blood of Christ, and we are challenged to see through the appearances to believe the reality. The opposite is true with a transgendered person. A man’s appearances – haircut, makeup, attire, perhaps even bodily organs – may have been altered or disfigured in such a way that people assume he is a woman. But in his essential identity, he remains a man.

Dawkins’ remarks, though, prompt a deeper analysis. Transgenderism has been widely discussed, but relatively little attention has been given to its spiritual dimension.

In the words of consecration, to which Dawkins refers, the priest says, “This is my Body.” The words call to mind the Incarnation, that the Word was made flesh. From his mother’s virginal womb, Jesus assumed, and retains for all eternity, a human body.

The Devil can never get over it. He hates the human body for a number of reasons, not least of which is that, being pure spirit, he sees it, and all matter, as beneath his angelic dignity. To rub salt in the wound, it was in and through a human body that God himself redeemed the human race and opened the gates of heaven that, for the Devil and his angels, remain forever closed.

To be human is to be body and soul, not as loosely tied elements but as an essential unity. A male human has a male body and a male soul. A female human has a female body and a female soul.

That a soul is male, or female may surprise us since we often associate sex only with the body. But we are sexed persons, not just sexed bodies. A man is a man because the maleness of his soul acts through and finds expression in his body. Jesus, in assuming a human nature, had and still has a human male soul and a human male body.

Transgenderism, however, seeks to drive a wedge between this body-soul unity, claiming that a human person could be born with the soul of one sex but the body of the other. Were such the case, it would not be equivalent to being born blind or without a limb. Those deformities in no way detract from the essence of personhood. The transgender claim is far more fundamental, alleging a disconnect in the human person himself. To deny that essential unity is to say that God made a mistake.

Transgenderism does not just distort the human person, though; it mocks God himself, in his Trinitarian essence. God made man in his own image. (Genesis 1:27) We generally understand that to mean that man images God in his capacity to reason and will. Man can know what is good and true and choose it and love it.

The complementarity of the sexes, however, forms a subtle and largely underexplored reflection of God. The doctrine of the Trinity tells us that there exist three ways of being God. The Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit are each complete expressions of divinity. The only thing each is not is the other.

An analogy of that relationship exists among human persons. As there are three ways of being God, so are there two ways of being human. A man and a woman are each complete expressions of a human person. Neither lacks any quality of humanness; the only thing each is not is the other.

The transgender movement, however, collapses that distinction, not just for an individual but for the entire human race. It claims that chasm can be bridged, that difference is not so different. There are then no longer two ways of being human, but one, and one that can take different forms for different persons at different times.

In this one movement, then, the Devil shakes his fist at the two great mysteries of our faith, the Trinity and the Incarnation.

Jesus says, “This is my body,” but we cannot say that of ourselves. Our body belongs not to us, but to God, and he will not be mocked. Dawkins’s remarks call us to see transgenderism not merely as a cultural flashpoint, but as a concentrated assault on the human race and its propagation. Contraception and abortion are one part of it. But transgenderism gives the coup-de-grâce; it denies the essential complementarity of the sexes, the basic necessity for the continuation of the human race.

Still, the spiritual perspective includes compassion for those who are the victims of the movement. The culture, and even some voices within the Church, have led many people to believe that their bodies are wrong and do not express their personhood – which only traps them in further confusion and error.

Rather, we hold fast to the truth of God’s design. That truth, like the human person, does not change, but it does transform us. It allows us to receive as a gift what the devil sought for himself: a share in God’s own life. In the end, when Christ says, “This is my body,” we pray that that includes every one of us, body – and soul as well.

__________