The great and good G.K. Chesterton once said that, of all the stories he had read, The Princess and the Goblin, a fairy tale by George MacDonald, is the one he found most like real life. That book, he claimed, had “made a difference to my whole existence.”

That’s a tremendous claim. But traditional fairy tales, contrary to what some might think, are like real life because they are ordered to happiness, and this implies a world of meaning. And where there is meaning there is someone to mean it, as Chesterton noted. The conditions for happiness are as confounding in fairy tales, however, as they are in real life. Be home by midnight or the coach turns back into a pumpkin. Eat an apple and death enters the world.

The Princess and the Goblin is specifically like real life, according to Chesterton, because the events happen in and around home, where the worst and best things are nearby.

The story goes like this. Goblins, demon-like creatures, live inside the darkness of a mountain in self-exile as a way to evade obedience toward an ancient king. And they nurse an endless grudge towards his ancestors.

One night these demons tunnel into the wine cellar of the reigning king’s home to kidnap the princess. The king’s guards are overwhelmed. Unafraid, a young boy – a miner – fights to defend the princess, routing the goblins by making up verses that they can’t bear to hear and stomping on their weak feet (iniquity cannot stand).

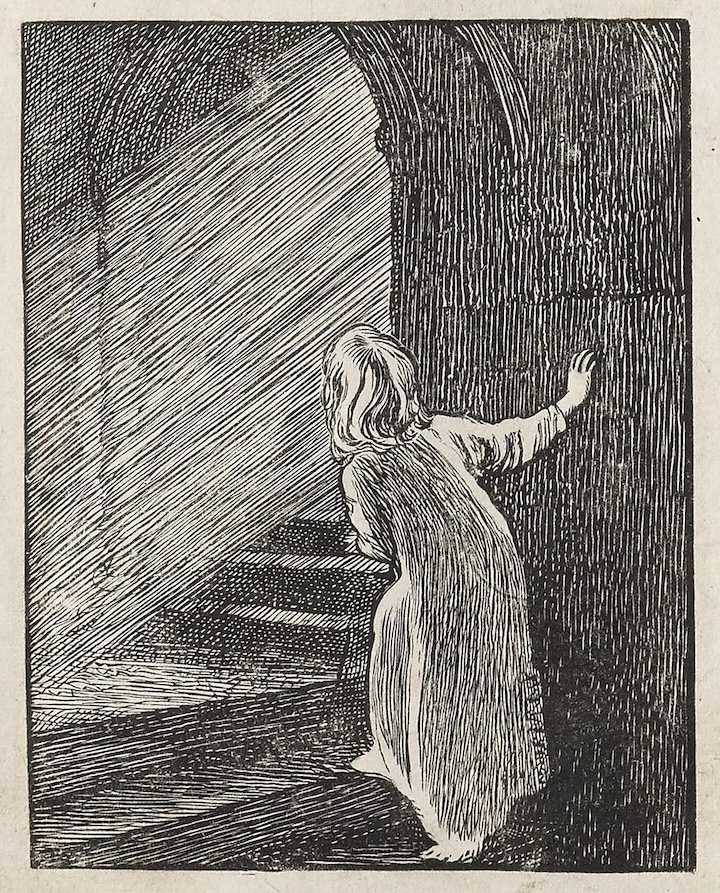

Crucial help also comes in a mysterious way from a certain lady who lives in a tower room in Princess Irene’s castle home.

Why write about princesses? MacDonald posits this question at the start of his story and immediately answers: because every girl is a princess, daughter of a king. By logical inference, every boy is likewise a prince, son of a king.

The Princess and the Goblin appears to make a quiet claim for the common origin of humanity in God, the King of all of us. And further, the story implies that demons wish to take captive into darkness every child. Evil is parasitical and seeks to destroy the goodness and beauty that marks Creation.

The Princess and the Goblin offers several parallels to our time and also some differences worth examining. But why bother at all with a tale that, on its surface, seems intended for children?

Given its glimpse into a world of moral clarity, the story reinvigorates us with its “center of sanity,” as Chesterton calls the humble characteristics of traditional fairytales by which they convey to us timeless truths. Truths such as the hero’s soul will be sane; that he will be brave, full of faith, reasonable, and respectful of his parents.

Writers of fairy tales may invent their own worlds, George MacDonald argued in his own reflections on the genre, but not new moral worlds. Its laws may not be turned upside down. Moreover, as Chesterton observes, MacDonald sees the world bathed in divine love. The Princess and the Goblin, therefore, can help us to re-see our own world as similarly lavished by this Love.

As to terms of parallels between The Princess and the Goblin and our own moment, demons, as it were, have tunneled into the basement of our homes in many ways, notably via the Internet. They threaten to take captive our children by leading them into the darkness of various falsehoods, as we can see in the meteoric rise of the transgender craze.

The King’s guards, namely, parents, schools, and even some churches, appear overwhelmed; unable, unwilling, ill-equipped, or afraid to protect our children. These demons differ from the ones that live inside the mountain as in The Princess and the Goblin or glide through the air unseen as in our own world. They are ordinary men and women, but demon-like in the serpentine doubts they raise and the lies they spread.

We must meet certain conditions to attain happiness? Obedience to a King? No, they tell us, often surreptitiously in various forms of entertainment for children. You should make your own rules. Be created in your own image. We all make ourselves. Self-creation leads to happiness.

The Princess and the Goblin doesn’t expressly confront transgenderism, but it implicitly addresses it by relating the wisdom of the ages: girls are girls, and boys are boys. They share a common aim: to grow up to be men and women of virtue, brave and good and strong in character.

In the story, eight-year-old princess Irene rescues Curdie (who earlier had protected her), the miner boy, hopelessly trapped in the dark labyrinth of the mines. She accomplishes this not by identifying as a boy, or by denying any physical difference between boys and girls, but rather through goodness, courage, and humble confidence in a person who is trustworthy, wise, and supernaturally powerful.

The person is Irene’s great-great-grandmother. Her figure, tied with the moon, roses, and a blue cloak, points to another ancient Mother. Chesterton admits that later in life he came to give a more definite name to the lady watching over us from the turret. The lady spins a shimmering and nearly invisible thread for Princess Irene to take up and follow when in danger.

The invisible thread suggests both a rescue rope and Jesus: image of the invisible God, “spun” from Mary in his human nature, the light that shines in darkness. This symbol of Jesus leads the children out of sensible darkness. In real life, Jesus, true God and true man, leads us out of spiritual darkness.

For the light of his countenance shines upon each of us; reason is placed in us and teaches us to discern good from evil. (Cf. Aquinas on Ps. 4). We have the light of revelation to dispel the blindness of error and know that in the image of God, male and female, He created us, for everlasting happiness with Him.