The Devil likes to make us stupid, particularly those of us who think we’re smart. He’s had a very good run for quite a while in the secular world. But he’s also done pretty well lately even in the Church. At present, his strongest game is to mesmerize us with simple oppositions: progressives/backwardists, tradition/development, synodality/rigidity, truth/mercy. Once that sort of thing gets up a head of steam, many people don’t think about anything. They just join one party – or another.

The usual Catholic response is to say we’re a “both/and” faith. And that’s good – for a start. But it doesn’t resolve an ever more urgent question: What do we mean by progress? Or tradition? Or mercy? Above all, by Truth? We need people to dig – and dig deeply – into such questions, people with learning and discipline, wisdom and consistency. Of which there are few, in any generation. Which is why we often need to resort to earlier, brilliant predecessors.

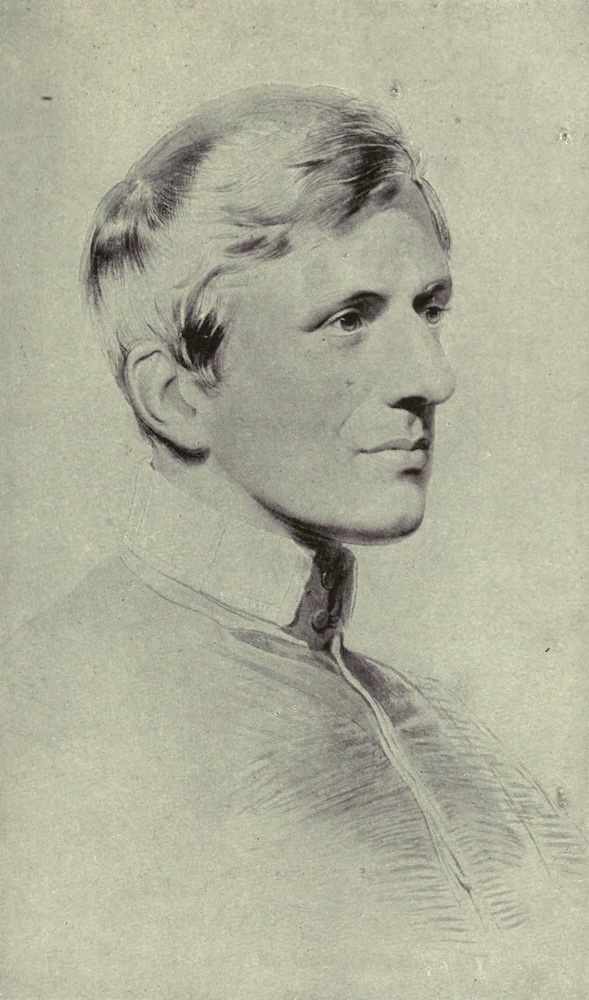

It’s telling that in our present moment of confusion, the name of St. John Henry Newman is often cropping up, not only – naturally – among those who believe in his criticisms of liberalism in religion. But he’s being invoked even among those who believe – much less plausibly – that “paradigm shifts” are somehow in a direct line of descent from Newman’s brilliant exposition of “development of doctrine.”

All that remains to be sorted. And fast. The present writer is willing to bet that we’ll hear Newman’s name repeated, and also taken in vain, often between now and next October’s concluding session of the Synod on Synodality. The bishops of England and Wales, and our own American bishops, have in recent weeks petitioned Rome to name Newman a Doctor of the Church. So, like much else these days, even the great Newman is about to become a bone of contention.

The title of the present column – “Holiness rather than Peace” – is a phrase that Newman came upon in his teenage years while he was still a kind of evangelical. But that robust sentiment remained in him even as he progressed through later phases: to the established Church in England, to Anglo-Catholicism and its (fictional, as he came to believe) via media between Protestantism and Catholicism, and finally to the Catholic Church. It encapsulated his steady belief that true religion required definite truths, and not only “notional” truths entertained in the mind, but truths made “real” by being incorporated in Christian lives.

And strictness as well. That kind of universal call to holiness – long before it became explicit at the Second Vatican Council – meant not bending conscience or mercy or pastoral practice to personal experience, but transforming personal experience under God. Newman was quite aware of the psychological and personal factors in the difficult process of conversion. But the aim of the Faith was not to make us comfortable on Earth but to prepare us for eternal life in Heaven.

That calls for a deeply demanding, not a superficially comforting Faith because it confronts the toughest problem of all: Conversion – turning the human person from pursuing his/her own desires to following the will of God. In classical terms, from pride, sin, and death, to – no, not easy “listening” to one another – but humility, grace, life.

As Newman put it in a celebrated passage:

Quarry the granite rock with razors, or moor the vessel with a thread of silk; then may you hope with such keen and delicate instruments as human knowledge and human reason to contend against those giants, the passion and the pride of man. (The Idea of a University)

In the final report of the recent session of the Synod on Synodality, sin is mentioned only once (in the official translation), and that as the rather abstract offense “the sin of racism,” which probably never turns up in Confession – a sacrament that goes unmentioned as well. “Reconciliation” does turn up, mostly in social contexts of polarization. Heaven and Hell? Nothing. In short, there’s a great deal about getting along, in the Church and the world, but the ultimate goal of the Christian life – why are we engaged in “communion, participation, mission”? – is not visible.

Amid the many specific controversies in the Church, therefore, there is an overall orientation we need to recover from Newman. But there are also several particular points where, properly understood, he could greatly help us. Among them, his expositions of:

- The Church of the Early Fathers

- The Need for Authority

- Development vs. Corruption of Doctrine

- Conscience as the “aboriginal voice of God” (not a personal concoction)

- Consulting the Faithful

Almost needless to say, on every one of these points, Newman is neither rigid nor progressive, but the true voice of a living tradition that remains faithful to Jesus while speaking to the times, in fact to every and all times. You might even argue that he was the first one to recognize the differing historical contexts of the Church in previous ages without thinking that historical contexts invalidated belief in perennial truths.

For these and many other reasons, I’ll be offering a six-week online course on “The Catholic Heart of Newman” in January. We’ll be reading Newman’s actual words from a variety of original texts so that we can all have a much clearer idea of what he said – and didn’t say – about some of the burning questions that bulk so large at this moment.

I’m looking forward myself to going through this material. Reading Newman can’t help but be enlightening and an aid to replying to misuse of his work. If you want a taste of how this great saint and predecessor speaks to us, here’s just a short bit:

The heart is commonly reached, not through the reason, but through the imagination, by means of direct impressions, by the testimony of facts and events, by history, by description. Persons influence us, voices melt us, looks subdue us, deeds inflame us. Many a man will live and die upon a dogma: no man will be a martyr for a conclusion. (Tamworth Reading Room)

Who else but Newman could so beautifully combine the personal dimension of faith in Jesus with the dogmatic element?

Intrigued? Please join us, starting January 3 online, and once a week thereafter. Register at TCT Courses. You’ll also find there courses on Dante, St. Augustine, St. Edith Stein, and much more.