Last October, The Catholic Project, which I direct at The Catholic University of America, published initial results from the largest survey of American Catholic priests in more than 50 years, the National Study of Catholic Priests (NSCP). Our initial report looked to answer several questions, including whether or not priests are flourishing (they are) and how the abuse crisis, and the Church’s response to that crisis, has affected trust and confidence between priests and bishops (it has, and not for the better).

Last month, our team published a second report laying out some additional insights from the NSCP, looking more closely at polarization within the presbyterate, particularly between older and younger generations of priests.

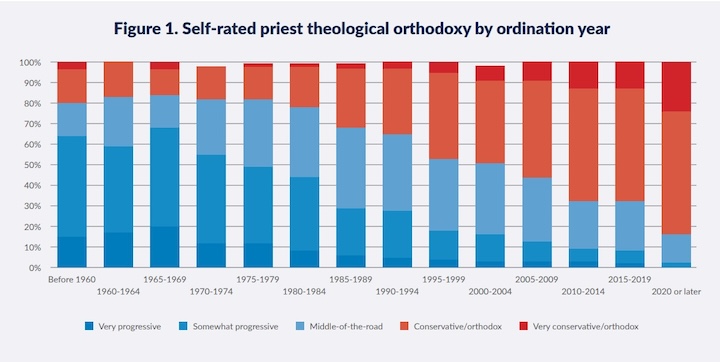

Older priests are more likely to describe themselves as theologically “progressive” and politically “liberal,” while younger priests are more likely to describe themselves as theologically “orthodox” and politically “conservative.”

This result, in itself, was not especially surprising. Anecdotal evidence suggested a similar trend for decades, and other recent studies of American Catholic priests have shown a similar conservative trend among younger priests. Notably, recent comments from both Pope Francis and Cardinal Christophe Pierre indicate that Rome is uneasy about what it sees as conservative trends among younger American clergy.

In short, our study demonstrated with hard data what everyone already knew: young American priests tend to be more conservative than their older peers. But that’s not all our data showed. It turns out that the narrative that young conservative men are taking over the American presbyterate isn’t as straightforward as it might seem.

First, our data suggests not so much a triumphant flood of conservative vocations as a near-total collapse of priestly vocations from men who see themselves as theologically progressive or politically liberal. What’s more, this collapse isn’t a sudden or recent trend, but appears to be steady and unbroken all the way back to the cohorts ordained in the immediate aftermath of the Second Vatican Council. If I were a bishop or vocations director, I would be very eager to better understand this collapse.

One explanation can be found in a homily given by the late Cardinal Francis George. Even a quarter-century later, his words retain a striking relevance:

Liberal Catholicism is an exhausted project. Essentially a critique, even a necessary critique at one point in our history, it is now parasitical on a substance that no longer exists. It has shown itself unable to pass on the faith in its integrity and inadequate, therefore, in fostering the joyful self-surrender called for in Christian marriage, in consecrated life, in ordained priesthood. It no longer gives us life.

Notice: Cardinal George said “exhausted,” not “dead.” It’s fair to say that recent years have proved that any reports of liberal Catholicism’s death have been greatly exaggerated. Nevertheless, if the exhaustion of liberal Catholicism explains, at least in part, the collapse of vocations from certain corners of the Church, Cardinal George’s warning about the inadequacy of a certain kind of “conservative Catholicism” is equally pertinent: “The answer, however, is not to be found in a type of conservative Catholicism obsessed with particular practices and so sectarian in its outlook that it cannot serve as a sign of unity of all peoples in Christ.”

Here, our study shows a significant (and I think, encouraging) deviation from the common narrative of liberal collapse and conservative advance among priests. While younger priests are much more likely to see themselves as politically conservative than their older peers, the youngest cohort of American priests is also the most likely of all the cohorts we surveyed to describe themselves as politically “moderate.” A plurality of priests (44 percent) in the youngest cohort describe themselves as politically moderate. If politics were a significant driving force behind “conservative” priestly vocations, one would expect the data to look quite different.

Add to this the fact that the youngest cohorts of priests are the most ethnically and racially diverse of all the cohorts we surveyed, and what emerges is a portrait of young American priests which cuts across the grain of several persistent stereotypes. Young American priests are more theologically orthodox, politically moderate, and ethnically diverse than any cohort of priests since before the Second Vatican Council.

If one were looking for priests who could avoid the “exhaustion of liberal Catholicism,” while also avoiding forms of “obsessed” and “sectarian” conservatism – if one were hoping for priests who could “serve as a sign of unity of all peoples in Christ” – one would probably look for a generation of priests that looks, at least on paper, a lot like the younger priests we have in the United States today.

But the priesthood, like all vocations, isn’t played out on paper. It has to be lived out amidst all the slings and arrows. As it happens, Cardinal George had something to say about that, too, in his homily:

The answer is simply Catholicism, in all its fullness and depth, a faith able to distinguish itself from any culture and yet able to engage and transform them all, a faith joyful in all the gifts Christ wants to give us and open to the whole world he died to save. The Catholic faith shapes a church with a lot of room for differences in pastoral approach, for discussion and debate, for initiatives as various as the peoples whom God loves. But, more profoundly, the faith shapes a church which knows her Lord and knows her own identity, a church able to distinguish between what fits into the tradition that unites her to Christ and what is a false start or a distorting thesis, a church united here and now because she is always one with the church throughout the ages and with the saints in heaven.

Francis George saw clearly what it meant to be faithful and also united in fractious and divided times. Our young priests – and all the rest of us, too – would do well to carefully consider the wisdom of his words.