Early in the sixteenth century, Pope Julius II decided to tear down St. Peter’s Basilica. The old basilica, built over the tomb of the Apostle by Constantine in the fourth century, had had a good run, even by Roman standards. But after twelve centuries of earthquakes, pillaging, and general neglect, Old Saint Peter’s was in danger of falling down. So Pope Julius gave up his plans to renovate and had the thing torn down and replaced.

The basilica we know today with its majestic dome – the St. Peter’s of Bramante and Michelangelo and Bernini – was begun in 1506 and consecrated in 1626. Which is to say that the St. Peter’s we know has stood for only a third of the time that its ancient predecessor stood.

If tearing down one of Christendom’s most hallowed sanctuaries wasn’t enough, marble for the facade of the new basilica was sourced locally and relatively cheaply from one of Rome’s favorite quarries: the Colosseum. Romans, particularly in the Middle Ages, but well beyond that, were not fussy about repurposing stone from old buildings and monuments.

Stripping marble from the Colosseum may seem an act of historical and cultural vandalism to us today. Repurposing the beautiful stone for something as grand as St. Peter’s seems positively reverential compared to some other uses to which the Romans were known to put the Colosseum’s acres of marble cladding. They used to crush and burn it to make quicklime.

What sort of culture has the audacity to use the Colosseum (and not just the Colosseum but most of the ancient Roman buildings) as a rock quarry? What sort of culture has the temerity to tear down one of the world’s most venerable buildings, like Old St. Peter’s, and yet has the confidence, capacity, and vision to build something as magnificent as the basilica that stands over the tomb of St. Peter today?

I remember being struck by this incongruity while in Rome some years ago. On the one hand, one cannot but lament this seeming indifference to the preservation of monuments we now think of as having irreplaceable cultural and historical significance. Yet this same willingness to plunder the past produced some of the greatest achievements of art and architecture in all of Western civilization.

We would never think of tearing off bits of the Colosseum to build a new church today. But neither do we seem capable of building anything of the lasting significance and beauty of St. Peter’s. We might attempt to maintain or refurbish an ancient building, but it is hard to imagine simply tearing it down and even harder to imagine our culture building a replacement that might rival or exceed the enduring beauty and magnificence of the original.

I found myself wondering, that day in Rome, if there might actually be a causal connection between a culture’s willingness to let go of the past – to allow the past to fade into memory or even be forgotten – and a culture’s capacity for the kind of creativity and confidence to build something at once as new and magnificent as St. Peter’s?

Our world has a hard time letting go. Museums, which we build to house beautiful things, but also curious, or even merely old things, are a relatively recent invention. The ancient and medieval worlds had nothing like the museums in the sense that we have them now. Yes, there were collections of art and sculpture and so forth, but the large-scale preservation of the minutest artifacts of the past is a distinctly modern phenomenon.

We studiously preserve the detritus of past eras yet build little that would be worth preserving a thousand years from now, if it even lasted that long. What we create these days is rarely intended as permanent, or even of enduring beyond a generation or two. It’s not just architecture. Consider how much of contemporary art and literature consists in peddling nostalgia, of endless sequels and prequels, or of remaking old movies, this time with better, modern special effects.

Don’t think that I’m undervaluing the past. Memory is a fundamental part of human existence, in a way it’s the greatest part. We cling to that which we love and hold dear, and we know the pain of loss all too well. A desire to explore and learn from the past is a wholesome thing. The longing to preserve and sustain what is good is natural to us, just as forgetfulness, at least of the most important things, is death to any society or civilization.

Still, I can’t shake the feeling that an unnatural preoccupation with preservation – our clinging too tightly to the good things of this world – goes hand in hand with our diminished imagination for what might yet be. The horizon of our experience opens not only before us, but closes behind.

“What has been, that will be; what has been done, that will be done. Nothing is new under the sun!” Thus spoke Qoheleth.

Meanwhile, we’re all stuck somewhere in between. The transience of this world, of ourselves and all we build and cherish, remains a stubborn fact of human existence. That at least can’t be blamed on the particular maladies of modernity.

Forgetfulness, too, is part of God’s Providence. Forgetfulness can even be liberating, as when mercy drowns out regret. Maybe our culture, in which everything is cataloged and stored forever in “The Cloud” and which seems to forget nothing except what is important, could stand to forget a few things. Maybe that would allow us to remember the more important things, or even ponder some new things.

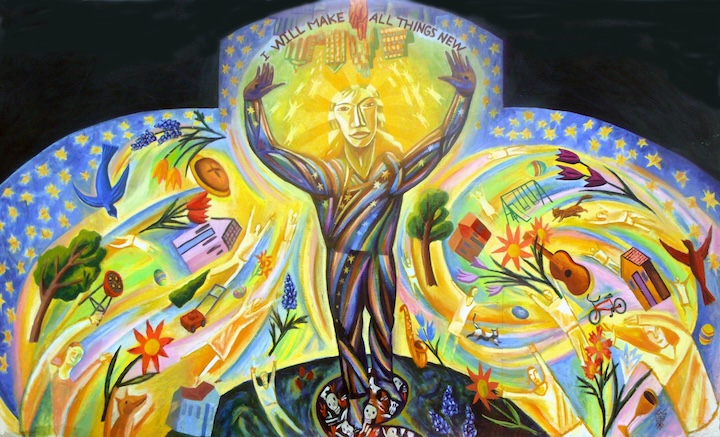

Advent is a good time to reflect on all of this. In Advent, the Church reminds us of the end of all things even as she prepares us to celebrate the one genuinely, radically new thing that has happened in the whole history of creation. What joy there is in gazing upon that Child in the manger! It’s enough to make you let go and forget all else.