Three-quarters of a century ago, one of the greatest Catholic minds of modern times, praised by numerous secular thinkers as much as by his fellow believers, and whom T. S. Eliot called “the most powerful intellectual influence in England,” identified a truth that has only become more evident since he wrote: “Religion is the key to history. We cannot understand the inner form of a society unless we understand its religion. We cannot understand its cultural achievements unless we understand the religious beliefs that lie behind them. In all ages the first creative works of a culture are due to a religious inspiration and dedicated to a religious end.”

The new year marks the 75th anniversary of Christopher Dawson’s Gifford Lectures at the University of Edinburgh. For over 130 years, the Gifford Lectures have been one of the most prestigious scholarly forums dealing with religion, science, and philosophy. Adam Lord Gifford, a Scottish judge and intellectual, established the series in order to “promote and diffuse the study of Natural Theology in the widest sense of the term – in other words, the knowledge of God.” The lectures began in 1888 and, with the exception of the intervening years during World War II, have been delivered continuously ever since.

Many pre-eminent thinkers in various fields delivered these lectures over the years, including philosopher Hannah Arendt, physicist Niels Bohr, French philosopher Etienne Gilson, mathematician and philosopher Alfred Lord Whitehead, the late contributor and friend of TCT Ralph McInerny, political philosopher Roger Scruton, and British evolutionary biologist Richard Dawkins (a figure for treatment another day).

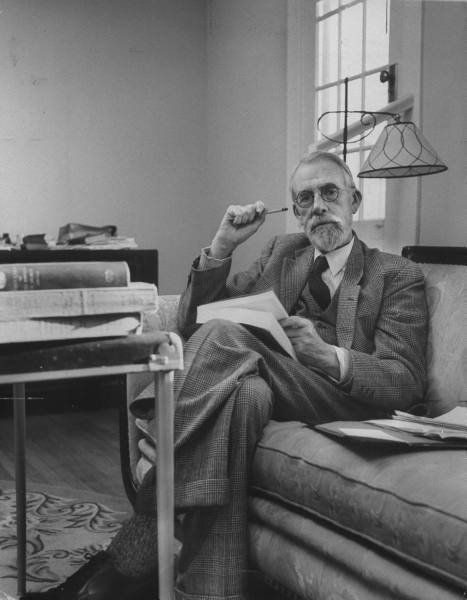

Christopher Dawson (1889-1970), inimitable Catholic historian of religion and culture, delivered his widely prized Gifford Lectures on Christianity as the driving force behind the development and emergence of Western culture. Dawson expanded on these lectures in his book titled Religion and the Rise of Western Culture which further elucidates, in contravention to popular thinking, the vibrant and fertile intellectual and spiritual history of the so-called “Dark Ages” which filled the cultural void created after the fall of the Roman Empire. It’s a great loss that many people today, even many Catholics, are unaware of his vital work.

Dawson makes the case that religion is the great impetus behind history and a decisive factor in the rise and fall of civilizations. For the West specifically, he writes that “Christianity was the first universal religion to unite men of all races and nations in a common faith.” His sweeping account describes the emergence of Western Christendom from the ruins of the Roman Empire to the age of Dante.

According to Dawson, this began with the conversion of the various Northern European “barbarian” tribes who formed a new spiritual community from the remnants of the Roman Empire through the amalgamation of Roman law and organization, Christian culture and tradition, and missionary zeal. Moreover, the rise of monasticism preserved classical culture and writings, fostered new scholarship, and created Medieval centers of learning which influenced the intellectual development of the West.

Chief among the innovations of monasticism was the emergence of a type of free society, “independent of external control and based on voluntary membership,” which sanctified work and poverty as the spiritual and economic heart of rural life.

Dawson ties together the history of Christian learning throughout the Medieval period by distilling other pivotal aspects of the era, including: the Byzantine cultural and religious influence; the emergence of the papacy as a unifying political and spiritual force; the classical and artistic achievements of the Carolingian Empire; the religious and cultural significance of the Crusades and of Medieval reform movements; chivalry and courtly culture in the feudal world; and the establishment of schools and universities, which laid the foundation for future Western scientific and intellectual disciplines and discoveries.

He deftly integrates all of these historical threads, describing how each critical development was nurtured by Christian institutions, ideas, and practices. We see these contributions today in our Constitutional political system based on the concept of natural law and the dignity of the individual; in the emphasis on education, literacy, and the ability to know the truth about the world at our schools and universities; and with the development of sacred art, architecture, and culture that still exist throughout the West (the controversies over the preservation of Notre Dame Cathedral in Paris show the lasting influence, magnificence, and enduring impact of Medieval art and architecture).

For Dawson, the dynamic changes brought about by the Christian culture of the Middle Ages are part of Western culture more broadly in innate and inextricable ways. “The importance of these centuries. . .is not to be found in the external order they created or attempted to create, but in the internal change they brought about in the soul of Western man – a change which can never be entirely undone except by the total negation or destruction of Western man himself.”

Indeed, the total negation of traditional Western man is the goal of modern-day “progressives” who in their Nietzschean Will to Power, seek the destruction of Christianity, family, and gender through various ideologies and in illusory calls for “social justice.” Dawson incisively describes how, even in our day, revolutionary and scientific ideologies are influenced, often indirectly and unconsciously, by the spirit of Western religion.

We in the West have become detached from our religious culture and our Western moral tradition. Dawson once observed, “It is religious impulse which supplies the cohesive force which unifies a society and culture. . . .A society which has lost its religion becomes sooner or later a society which has lost its culture.”

All is not lost, however. As Dawson reminds us in his conclusion, “if the barbarians of the West had learnt to think such thoughts and speak such a language, it shows that a new Christian culture had been born which was not an alien ideal imposed externally, but the common inheritance of Western man.”

We would do well to rediscover this inheritance by familiarizing ourselves with the works of Christopher Dawson, starting with Religion and the Rise of Western Culture.