We are at the summit of the Church’s liturgical year, the redemptive triptych we call the Easter Triduum. And with the commemoration of the Lord’s Crucifixion that precedes it, and the celebration of his Resurrection that follows it, it’s understandable to look on Holy Saturday as a quiet time, an opportunity to catch our collective breath before we celebrate the glorious final act. Understandable, but not advisable.

Our weekly recitation of the Nicene Creed with its simple declaration that Jesus “died and was buried” may inadvertently contribute to this tendency. One might easily get the impression that the Lord’s burial was a mere holding action between the agonizing events of the previous day (“For our sake he was crucified under Pontius Pilate”) and the stunning triumph of the following day (“and He rose again on the third day in accordance with the Scriptures”).

But there’s more – much more – to that simple expression than meets the eye. The Apostles’ Creed points us toward that deeper reality when, after also declaring that Jesus was buried, adds: “he descended into Hell.” St. Paul refers to that abode of the dead, as “the lower regions of the earth” (Eph. 4:9) and elsewhere as “the abyss” (Rom. 10:7); it’s the place Jews called Sheol and the Greeks Hades.

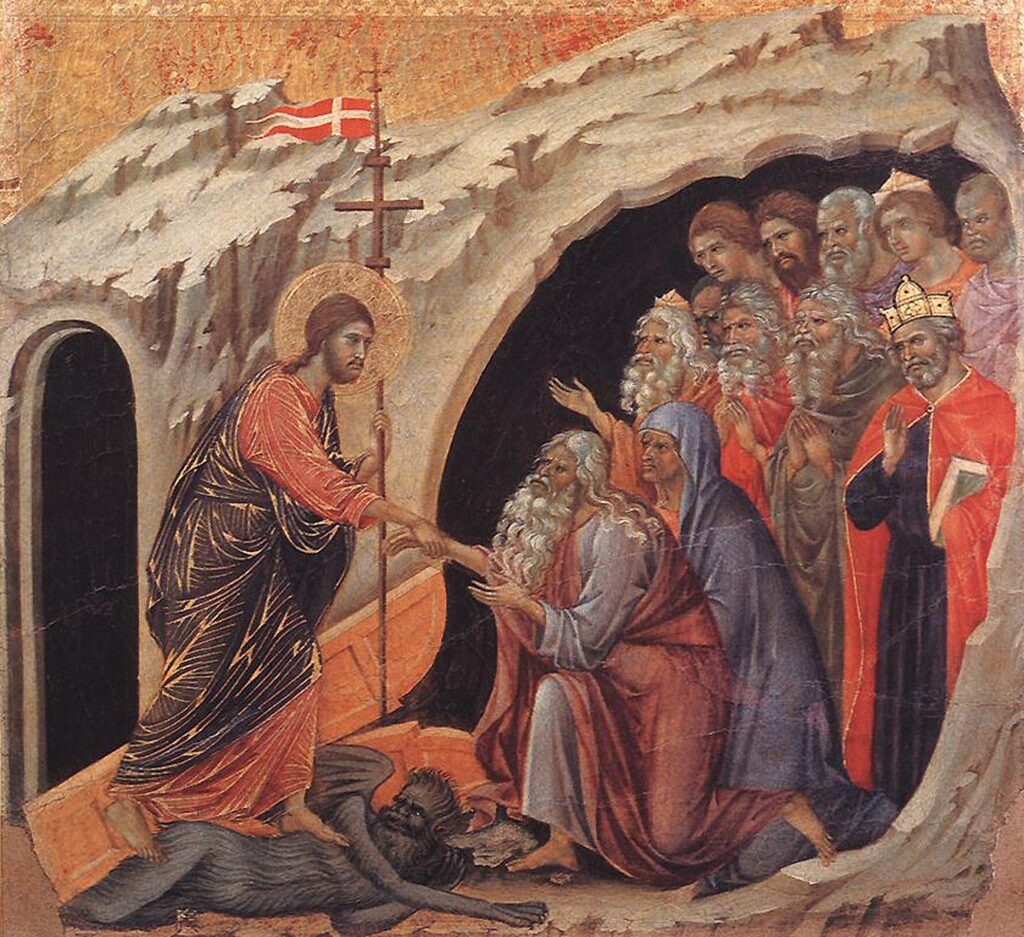

But why did the Lord descend into Hell? According to the Catechism, to bring “the Gospel message of salvation to complete fulfillment.” (643) It was to continue his messianic mission that Jesus preached the Gospel “even to those who are dead.” (1 Peter 4:6) While his body remained in the stillness of the tomb, Jesus went and “proclaimed to the spirits in prison.”(3:19).

Jesus’ mission to “bring us to God” (3:18) didn’t take a pause; it simply continued in a new mode, in another realm, and with a different audience. That audience was comprised of those holy souls who had been patiently waiting in Abraham’s bosom (“the limbo of the Fathers,” as theologians have called it) for the coming of the Savior. It was to them that Jesus ministered, reassuring them that they would soon be rescued to join him in Heaven.

It’s also true, however, as both Creeds affirm, that Jesus’ lifeless body was laid in a tomb, that His death was real. So, while the souls of the faithful departed enjoyed His presence, as far as those who were then alive were concerned, Jesus had simply fallen silent. Josef Ratzinger powerfully expressed this in his masterful Introduction to Christianity, the disciples experienced Holy Saturday as “the death of their hope.”

As with those disciples from Emmaus who had left Jerusalem crest-fallen after the Crucifixion, “something like the death of God had happened,” Ratzinger comments. In an interesting twist, he connects these events to the cry of Nietzsche’s Madman: “God is dead, and we have killed him.” The Madman spoke better than knew, for as Ratzinger interprets it, “This saying of Nietzsche’s belongs linguistically to the tradition of Christian Passiontide piety; it expresses the content of Holy Saturday, ‘descended into Hell.’”

Even the silence of God speaks volumes, however. As Ratzinger observes, not only “God’s speech but also his silence is part of the Christian revelation.” But what does this silence reveal? What can we possibly learn from “God’s seeming eclipse,” from “the absent God”?

Most especially, what Ratzinger calls “the truth of God’s abiding concealment.” As such, it serves as a powerful reminder that God dwells in mystery, in light unapproachable; that He is deus absconditus, the hidden God. For God is not only the comprehensible Word [or logos] that comes to us,” Ratzinger states, “but also the silent, inaccessible, uncomprehended and incomprehensible ground that eludes us.”

Does all this not call for a humble response on the part of God’s creatures? Is this not an antidote against the kind of over-familiarity with God that threatens to bring Him down to a merely human level?

God’s transcendence throws into stark relief His amazingly great condescension in the Incarnation and the subsequent redemptive events in Jesus’ life. These mysteries, which, according to Ignatius’ letter to the Ephesians (to which Ratzinger refers in a footnote), were “loudly proclaimed in the world by the preaching of the apostles,” but were “accomplished in the stillness of God,” that is, in the stillness of eternity, in God’s abiding concealment. Which is why even Satan was taken by surprise.

But there’s even more. The descent into Hell not only reveals something about God; it also reveals something about us. As God’s image bearers, we humans are intrinsically communal in nature. Accordingly, deep down we carry what Ratzinger calls “the fear of loneliness. . .the anxiety of a being that can only live with a fellow being.” Death, he explains, is a “door through which we can only walk alone” – it is “absolute loneliness” – and Hell “the loneliness into which love can no longer reach.”

That is the horror this “death of God” evokes on this Sabbatum Sanctum, this Holy Saturday. Thankfully, we don’t have to remain perpetually in such dreadful loneliness, as Existentialism requires us to do. But it’s good that we dwell there at least for a time, for only then can we begin to comprehend the measure of God’s love in rescuing us from such a state.

That’s another good reason the Church should seek to rediscover the importance of Great and Holy Saturday, as the Eastern Orthodox churches call it, as well as of what Ratzinger refers to as that “forgotten and almost discarded article” of the Apostles’ Creed.