For the first time in a decade, the Holy Shroud will be on public display at its home, the Cathedral of Saint John the Baptist in Turin.

The Vatican has yet to issue any formal endorsement of the astonishing claim that the Shroud is a true acheiropoieton (an icon not made by hand), indeed the cloth in which the body of the crucified Christ was wrapped and which Mary Magdalene, John, and Peter found three days later in the empty tomb (John 20:5-8).

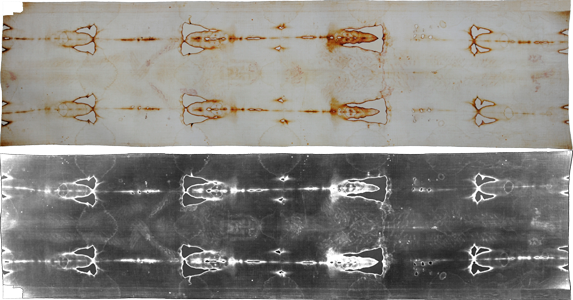

If you were to travel to Italy before the exhibit ends on May 23, you wouldn’t see what’s truly stunning about the 14 ½- x 3 ½-foot cloth. For that, you have to see the negative version, as did an amateur photographer, Secundo Pia, when he took the first photographs of the Shroud in 1898 and saw, as he lifted the photographic plate from its chemical baptism, the man’s face as a positive image on the negative. Pia had no doubt whose face it is, and his discovery launched “sindonology,” the scientific study of the Shroud.

For the 2010 exhibition, a new book and a fascinating documentary have been released, both of which deal forthrightly with the controversies that seem warp-and-weft with the fabric of the Shroud itself.

The Truth About the Shroud of Turin: Solving the Mystery by Robert K. Wilcox is the most current survey of the key issues about the Shroud and includes a brief description of the very recent discoveries of Dr. Barbara Frale, about which more in a moment. And the History Channel recently premiered (and offers now on DVD) “The Real Face of Jesus?” – which covers much of what’s in the Wilcox book but also chronicles the attempt by computer-graphics expert Ray Downing to reconstruct the face on the Shroud using modern wizardry and some old-fashioned artistry as well. The result of his forensic animation is stunning.

Perhaps the most startling thing about the Shroud (besides the fact that it once may have covered our Lord’s body) is that after so much time and effort – after more than six centuries of inquiry and more recently of extensive scientific testing – no one is able to say for certain how the image on the cloth was made. On the one hand, we do have an answer (albeit miraculous) if we believe the image was imprinted by the Resurrection; on the other hand, nobody has explained how the image may have been faked, if it is a forgery, especially since the fake would have been concocted sometime before the fourteenth century – at a time, in other words, when such a sophisticated fraud (one incomprehensible to twenty-first century science) was all but impossible.

Mr. Wilcox describes the many skeptics and believers (some of them troubling), tests and arguments, bizarre fantasies and devout opinions that have attended the Shroud since it first surfaced in Europe about 1350. That the cloth still exists is itself a miracle, so many times was it stolen, burned, hidden, damaged, and repaired.

This last matter is key. There have been two serious scientific studies made of the Shroud in the last several decades. The first was by the Shroud of Turin Research Project (STURP), which was given access to the relic in the early 1980s; the second was in 1988 when a piece of one corner of the Shroud was removed for radiocarbon dating. STURP researchers came away leaning towards confirmation of the Shroud’s authenticity, although they cautioned that further analysis of the fabric was necessary. But those later radiocarbon results seemed to prove that – whatever the Shroud is – it isn’t from the time of Christ but dates to somewhere between 1260 and 1390. For some, that was the end of the debate.

But there are problems:

-Radiocarbon dating of textiles is often wildly inaccurate, since later bacteria and pollens can permeate fibers and give false readings.-The piece taken from the Shroud for testing may well have been a patch from a thirteenth-century repair.-Besides the image and blood of the crucified man, there are remnants of various substances on the cloth, including one plant (a chrysanthemum flower) that according to botanists grows only in Israel.-NASA scientists using advanced digital processing discovered lepton images of coins on the crucified man’s eyes, which have been identified as dating from the rule of Pontius Pilate.

Perhaps the most remarkable new discovery was made last year by Barbara Frale, a scholar of the Knights Templar. Not only does she believe that the Templars were the Shroud’s guardians, but in close analysis of Shroud photos, she has found on the cloth faded words in Greek, Latin, and Aramaic (flipped as if in mirror image) that read:

In the year 16 of the reign of the Emperor Tiberius Jesus the Nazarene, taken down in the early evening after having been condemned to death by a Roman judge because he was found guilty by a Hebrew authority, is hereby sent for burial with the obligation of being consigned to his family only after one full year.

It is Christ’s death certificate, dating the Crucifixion to the year 30.

This is powerful and – I must say – convincing and makes the work of Ray Downing just that much more compelling. Scientists from the Jet Propulsion Laboratory have found that the Shroud image has a 3-D effect, in that it shows the peaks and valleys of the impression of the figure it once covered, and it’s an effect of which Downing makes astonishing use.

It now seems all but certain that this truly is the burial cloth of Jesus.