Mostly unrelated to the Synod on Synodality, my wife Sydny and I went to Rome in the last week of October. Upon arrival, we did have lunch with one journalist covering the synod: Robert Royal. You may have heard of him. We were exhausted because of jet lag, and Bob was weary of the synodal process. Walking around Rome, which Syd and I would do a lot of, is not nearly as tiring as “walking together” in a synod. Or covering it. But Rome does offer many compensations.

We began our second day in Rome with a tour of the Galleria Borghese, which houses a remarkable collection of paintings and sculptures in the Villa Borghese, 17th-century home of one of Italy’s great families. (Camillo Borghese of Siena had become Pope Paul V in 1605.)

Today, the Villa and the surrounding gardens are among Rome’s major attractions. The house was built by Cardinal Scipione Borghese, nephew of the aforementioned Paul V. As “Cardinal Nephew” (an official post at the time), Scipione engaged in what today would surely be illegal benefices that allowed him to build the villa and procure the art that fills it. (Scipione is buried in one of Rome’s most remarkable churches, the Basilica di Santa Maria Maggiore – or St. Mary Major.)

The Borghese Gallery features most prominently the work of two great artists: Gian Lorenzo Bernini and Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio.

Fr. Joseph Scolaro wrote here of Bernini’s Aeneas, Anchises, and Ascanius, one of a number of Bernini’s remarkable sculptures at the Borghese. Among all the Bernini works there, I found Apollo and Daphne the most arresting. In some ways, it’s not unlike Bernini’s The Rape of Proserpina, also in the Borghese. Both depict abductions by gods, each based upon stories told in the Roman poet Ovid’s Metamorphoses.

Apollo, ideal god among the gods, relentlessly pursues the nymph, Daphne. When he finally catches her, however, she turns herself into a laurel tree. Working with Carrara marble, Bernini shows Daphne’s fingers sprouting leaves, her flesh turning to bark. Never in a museum have I so wished to touch a work of art, but I resisted.

And this was the moment I realized that in Rome, particularly, and Catholicism, generally, there is no conflict between the classical and the Christian. You see it in museums and churches and especially in the Raphael Rooms in the Apostolic Palace.

The Borghese’s Caravaggio collection is remarkable. One painting, known as The Sick Bacchus, is thought to be an early self-portrait. It pairs with Boy with a Basket of Fruit – both painted when the artist was in his early- to mid-twenties. The collection then jumps ahead to 1605-06, a period in the last years of his young life when he was at the peak of his powers and fame. Madonna and Child with St. Anne (or Madonna Dei Palafrenieri, after the group that commissioned the work) is more colloquially known as Madonna and the Snake.

Our Lady, her mother, and the child Jesus look down at Eden’s snake. In other artists’ depictions, it is crushed solely by Mary, as in Genesis 3:15 (in Jerome’s Vulgate): “I will put enmity between thee and the woman, and thy seed, and her seed, and she shall bruise thy head, and thou shalt be ensnared by her heel.” Caravaggio being Caravaggio, depicts the Virgin and Jesus crushing the snake, the boy’s foot upon hers.

The papal grooms (the Palafrenieri) rejected the painting, and Cardinal Borghese scooped it up.

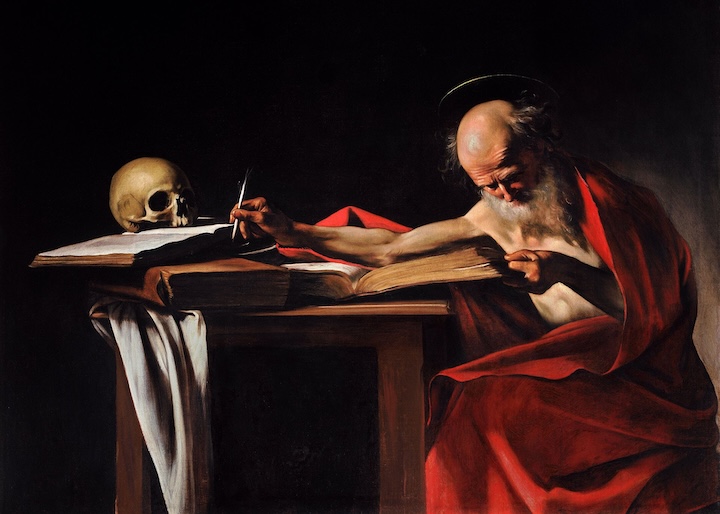

The Borghese also has Caravaggio’s Saint Jerome Writing. “This was probably the first of the painter’s works to come into the possession of Scipione Borghese,” the Gallery tells us, because the cardinal had helped Caravaggio with “legal problems,” which were many.

I’m going to skip over two more wonderful Borghese Caravaggios: David with the Head of Goliath and John the Baptist – both dated from 1610. (The Borghese has nine by Caravaggio in all – more than any other museum in the world.)

Grand as the Villa Borghese and its Gallery are, for me the highlight of the trip came later on that day when we met with art historian Elizabeth Lev for a tour of churches in central Rome.

Liz is the author of an extraordinary book, How Catholic Art Saved the Faith: The Triumph of Beauty and Truth in Counter-Reformation Art. It’s an insightful guide to that critical era in Church history (covering the end of the Renaissance and most of the Baroque period) and to the artists and paintings that responded with dynamism to the Protestant Reformation’s iconoclasm.

Many today think art is meant for wealthy intellectuals, which, given much modern art’s departure from the true and the beautiful, makes sense. But 400 years ago, great art gave inspiration to rich and poor, literate and illiterate, conveying heroes of the Bible, saints, and theology; visually portraying truths of the Catholic faith.

Ms. Lev took us around the Piazza Navona, most famous for Bernini’s Fontana dei Quattro Fiumi (Fountain of the Four Rivers), with extraordinary figures representing the Nile, the Danube, the Ganges, and the Rio de la Plata, and she regaled us with stories of Bernini’s embrace of the Counter-Reformation’s assertive Catholicism and his conflict with popes and rivals.

And I must mention that the enterprising Liz Lev runs a tour company. One of her expert guides took us through the Vatican and another through Rome’s ancient sites (see the photo at the end of this column).

But the true highlight of the trip for me came when Liz took Syd and me into San Luigi dei Francesi (Church of St. Louis of the French). The church has an interesting façade and is rather dark inside, so that to see art in some of its chapels you must drop coins into a box that turns on lights.

One such is the Contarelli Chapel, famous for Caravaggio’s St. Matthew paintings: The Calling of; The Inspiration of; and The Martyrdom of. This was the commission that propelled the artist to fame. To see them all together had such a powerful effect on me that I had trouble holding back tears.

Catholics need to see the riches of the Faith once again.