We have just recently celebrated Memorial Day, which, in addition to signaling the opening of swimming pools across the nation, is set aside to remind us of the lives sacrificed for our freedom in military conflicts throughout our nation’s history. Thoughts of Valley Forge, Gettysburg, D-Day and Iwo Jima should intrude at least intermittently upon barbecues, store sales, Rolling Thunder motorcyles, and poolside activities.

All kinds of deaths make the news, however, and many don’t fall into the category of those heroic and sacrificial deaths of young soldiers and sailors. Journalists often use words like “senseless” in describing them. There are the Waco biker fight deaths, for example, or the deaths of desperate migrants drowning in the Mediterranean; there are the mind-numbingly common drive-by shootings, suicides, and auto accidents. There are deaths in which elements of recklessness, carelessness, or bad judgment played a part.

And there are tree limbs falling through car windshields, lightning strikes, earthquake deaths like those in Nepal. There are freaky medical conditions and misdiagnoses. In fact, when you include all the deaths that don’t seem to satisfy our sense of purpose or trace a proper narrative arc for a life story, there are hugely more candidates for the title of “senseless” deaths than, well, “sensible” ones.

Even many of the war deaths are not immune to charges of senselessness, such as “friendly fire” incidents. And World War I poets like Wilfred Owen viewed that war as the senseless slaughter of a generation of young people to satisfy the greed, pride, or political machinations of the old.

There is something to be said for this natural human desire to separate deaths into those that appear merely premature, futile, or senseless and those that satisfy the rational or story-telling aspect of our species. This, however, also gets a lot wrong. For it leaves the great mass of human deaths lying in the “senseless” category, when we should be placing them in the category of “not fully understood.”

Denoting deaths as “senseless” assumes that, because we do not have or cannot penetrate the meaning behind this or that person’s end, there was none. In so doing, it comes perilously close to the same mentality that identifies “life unworthy of life.” If the person dying in a terrorist blast or a mine cave-in or a drive-by shooting or an Ebola outbreak experienced a senseless death, can we also call the life of someone severely handicapped senseless?

Those descending into dementia – where is the sense in that to our limited minds? Those suffering protracted pain, those identified as being in a persistent vegetative state – what is the point of their lives, or of postponing their deaths? Why do some live so long while others, in the words of The Band Perry song, find that “forever could be severed by the sharp knife of a short life”?

Of course, we want to stop terrorism, prevent violent assaults, learn more about natural disasters and disease, so as to prevent what seem to us untimely deaths. And contemporary scientists and inventors have devised many ways to help the handicapped live richer, fuller, more satisfying and productive lives (although we have also “progressed” in detecting handicaps prenatally, where they can be “treated” by abortion).

This is part of what it means to be human: to be stewards and co-workers in a world that is supposed to evoke in us more than marvel and wonder. But not less. The marveling and wondering are authentically human, too. And the occasions on which we summon enough humility to acknowledge how much we do not really know about God’s specific purposes in creating each of us are authentically human occasions.

Those are the times when we confess that we are not the Lords of Creation and thus lack the sweeping perspective of God, who surveys all of his multifarious creation throughout all of time, and perceives the intricate pattern of his Providence.

It is natural for human beings to tell stories that testify to the meaning in their own and others’ lives. There is nothing wrong with that. The problem comes when we jump from not being able to perceive the meaning in a given life to concluding that there is none.

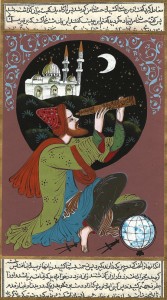

Then we roam near the territory of the mad astronomer in Samuel Johnson’s novel Rasselas. After years of closely studying the sky and the heavenly bodies, he fell into the insane belief that he actually determined their movements and operations: “The sun has listened to my dictates, and passed from tropic to tropic by my direction; the clouds at my call have poured their waters, and the Nile has overflowed at my command.”

No death is senseless in God’s sight. Because we are not God, that is not true of us. That doesn’t mean we don’t praise – and delight in – heroism and self-sacrifice, and direct our abilities to battle accident, disease, and other evils of the fallen condition. But in doing so, humility – one of whose definitions is self-knowledge accompanied by acceptance – is perhaps the most practical and productive virtue we can aspire to.