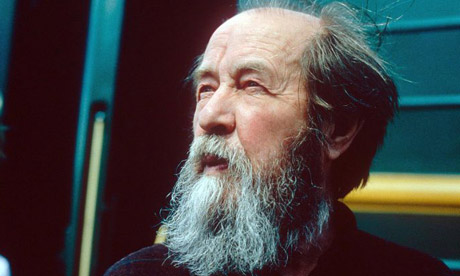

Today marks the 100th Anniversary of the birth of Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, the Russian author who, though he must be ranked as the most important writer of the past century, is no longer well known and even less well understood by Christians in the United States.

Solzhenitsyn’s mother was widowed before he was born, and the Bolsheviks confiscated her family’s land. She moved to Rostov seeking work, but much of Solzhenitsyn’s early life was spent sharing her poverty. Nevertheless, to be born in Russia in 1918 meant that one belonged to the first generation of the glorious Communist Revolution, and the new Marxist schools taught the young Solzhenitsyn that the principles of Communism would soon lead to the establishment of a totally new and evil-free epoch in human history.

When World War II broke out, Solzhenitsyn left the university in Rostov to serve as an officer in the Russian military. He was suddenly arrested in 1945 for comments made in a private letter to a friend that were deemed to be critical of Stalin. He was sentenced to eight years in the Soviet camp system; from there he was released into perpetual exile in Kazakhstan. He then began to write, drawing especially on the 12,000 lines of poetry he had secretly composed and memorized in the camps.

By 1962, Solzhenitsyn was able to return to Russia, but he did not dare to publish or even submit his manuscripts to editors. Signs of a cultural thaw began to appear under Khrushchev; Solzhenitsyn took the risk of sending – anonymously – a long short story about a single day in a single camp prisoner’s life to a literary journal called Novy Mir. The journal’s editor immediately recognized the value of the story and took it to Khrushchev himself, who gave permission for the publication of One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich.

The reception was astonishing. One eyewitness wrote, “Just walking through Moscow at the time was exciting, there were crowds of people at every newspaper kiosk, all asking for the same sold-out journal. I’ll never forget a man who was unable to recall the journal’s name and was asking for ‘the one, you know, the one where the whole truth is printed.’ And the saleslady understood what he meant.”

The author’s identity soon became known, and hundreds of letters poured in from former camp prisoners who, like Solzhenitsyn, had beaten the odds and survived. Solzhenitsyn soon conceived the idea of using their stories and memories to write a more comprehensive work on the camps. The cultural “thaw” quickly turned to a “freeze,” however, and the Soviet secret police began to hound Solzhenitsyn incessantly.

He nevertheless felt a moral duty to write what would eventually be titled The Gulag Archipelago. Solzhenitsyn had to work in secret and pass parts of this enormous manuscript from one underground secretary to another in order to preserve it. It was eventually smuggled out of the country and published in France. From there it was quickly translated into many languages, and the whole world learned the truth about the enormity of Soviet crimes.

It is easy to view Solzhenitsyn as merely the author of a powerful, two-part political exposé. Such a view, however, would be to overlook the true power and significance of his writing, for he did not simply tell us how terrible the Soviet camp system was, but explained why it was terribly wrong.

During his time in the archipelago, Solzhenitsyn had slowly but forcefully rejected the Marxism of his youth and embraced Christian faith. This conversion was not achieved, however, without a great amount of personal suffering and an even greater amount of personal reflection.

Marxism claims that some groups and classes of human beings are good and others bad, so to perfect itself, humanity must isolate and eliminate the bad people. Solzhenitsyn came to realize instead that the dividing line between good and evil lies within every, single, individual human heart.

The Marxist position thus argued that humanity would be perfected through the inevitable progress of world history. If the dividing line is within all human hearts, however, then only limited improvement is possible in this life, and degeneracy is always equally possible. The Marxist position is to be rejected, it seems, because it overlooks the reality of Original Sin.

Moreover, the Christian conscience forces human beings to attempt a justification for their acts and gnaws at or even devours them if they cannot find such a justification. The Marxists, however, provided their adherents not with conscience but with an ideology that justified evil deeds in the name of an unattainable end. Such ideological justification pushed the Marxists beyond the normal threshold of wrongdoing and made the destruction of millions appear not abhorrent or unthinkable but necessary and acceptable.

Marxism not only misunderstood the origin of evil, but likewise misunderstood what is to be done with its effects – with suffering. Solzhenitsyn came to realize that while there was no correlation between what he and the other political prisoners in the camps were charged with and what they were made to suffer, the Christians within the archipelago – at least the best of them – learned how to make suffering redemptive. That is, they knew how to turn their suffering into a continuous penance stemming from a continuous confession.

From there, they could turn to spiritual ascent through what Solzhenitsyn often called “self-limitation.” In his later years, he warned the West – in his lecture at Harvard and Nobel Prize speech – that the “free world” was embracing a materialist slavery of its own. That process is far more fully developed now than during Solzhenitsyn’s lifetime.

Such self-limitation begins to sound a lot like the self-limitation of Christ, who did not grasp at equality with the unlimited, but willingly limited himself and became human, accepting human form and human suffering, and proffering divine mercy thereby.

There’s a pointed lesson here for us today – because these are deep truths Solzhenitsyn uncovered for us that should govern every regime – every human life.