Today is the Feast Day of St. Robert Bellarmine, the man sometimes portrayed as the rock of the Counter-Reformation, the mighty Catholic fortress opposing the Mighty Protestant Fortress of the reformers’ hymn, the powerful Cardinal of the Inquisition with the dark Satanic beard, whose favorite and allegedly only word was “NO.”

Such a picture, however, is completely foreign to those who knew Bellarmine. And it clashes with the brief Autobiography he composed at the request of his fellow Jesuits in 1613, when he was 71.

The Autobiography was never intended for publication and lay dormant among the papers of the Society’s Roman College until it was brought out, long after his death, during his beatification proceedings by the “devil’s advocate,” the official assigned to challenge claims of holiness.

The Autobiography is now available in translation by Ryan Grant in a delightful little volume from Mediatrix Press. Since it is St. Robert’s feast day, perhaps the charitable way of proceeding is to consider his self-understanding as it appears in the Autobiography.

Born in the Tuscan hilltop town of Montepulciano in 1542, Bellarmine says that as a child he was good at most everything but excelled at nothing. He lists his skills: poetry, singing, playing musical instruments, and repairing hunting nets. He would stay up late at night reading Vergil in Latin and eventually composed his own poems and hymns in imitation of him.

He burned these works when he entered the Society of Jesus, just days before his eighteenth birthday, but he hardly abandoned ancient learning, since the Roman College’s curriculum featured the logic and philosophy of Aristotle. His gifts quickly led to his being assigned to teach topics such as astronomy, and Demosthenes in Greek. The latter subject presented a problem because he did not know Greek. But he taught himself enough to stay one step ahead of his students and, indeed, soon mastered the language. He would later teach himself Hebrew, as well, and went on to write an influential Hebrew textbook.

The Autobiography emphasizes that Bellarmine was very early in his life in demand as a preacher. But this presented a similar problem to his teaching of Greek, since requests to preach were frequent even before he had studied much theology.

He recalls satisfying one request by more or less cribbing from a Greek sermon of St. Basil’s. He eventually began formal theological studies at Padua, but was soon called to Louvain to preach. It was there that he completed his studies – by teaching Aquinas’ Summa Theologiae from beginning to end – which took six years.

Bellarmine says in the Autobiography that he chose to join the Jesuits over other religious orders because in the Society of Jesus he would never be offered or permitted to accept any dignities from the Church. Nevertheless, the dignities came and he was ordered to accept them. In 1599, he became Cardinal; in 1602, he was appointed archbishop of Capua, about 30 miles north of Naples.

In the Autobiography, Bellarmine seems especially pleased with his work there. Following the reforms of the Council of Trent, he chose not to hang around the papal court but actually to live in his archdiocese. He used the funds that came with the position to repair churches and support the poor. He preached frequently and encouraged his priests to develop better preaching skills.

Bellarmine was born on October 4 – the Feast of St. Francis of Assisi – and died exactly 399 years ago today. September 17, however, was traditionally the feast of Francis’s reception of the Stigmata. Bellarmine was especially devoted to Francis and, as a young Jesuit, visited Mont La Verna, where Francis received the marks of Christ’s Crucifixion. He probably wouldn’t have wanted to bump the Feast from the Roman Calendar, but would have preferred to remember the Stigmata along with his sainthood on this day.

Although he says little about it in the Autobiography, Bellarmine’s temporal fame rests predominantly on a large, three-volume set of writings against Protestantism that is usually referred to simply as The Controversies. This massive work is the source of his image as a great Nay-sayer. Yet Bellarmine is always astonishingly fair to those he criticizes. Indeed, Protestants sometimes thought he had actually improved their arguments in his summaries of them – before he proceeded to his criticisms.

In 1616, when the Galileo controversy arose, Bellarmine reached a compromise whereby Galileo agreed not to claim that he had a proof for heliocentrism, but was permitted to study the evidence quietly to see if the elusive proofs could be attained. Galileo never was able to find the proof he sought and, in any case, the agreement fell apart after Bellarmine’s death.

Many scholars think that the whole Galileo controversy, which flared up again in 1633, might not have ended so ignobly if Bellarmine had still been alive.

His final works were a series of spiritual reflections that were quickly translated into several languages. They became widespread favorites, especially among English Protestants.

Bellarmine’s political writings, too, were quite influential, but are too complex to go into in any depth here. I’ll be treating those in a forthcoming book. But as Robert Reilly has suggested in his America on Trial, Bellarmine influenced the American Founders; some knew his natural law views directly, others through British figures such as Algernon Sydney and Richard Hooker. It was Bellarmine, says Reilly, not Locke in the 17th century or Jefferson in the 18th, who first said, “All men are born naturally free and equal.”

Bellarmine was a skilled controversialist who was never afraid to argue robustly and vigorously for Catholic truth. Yet his calm and serene argumentation stands as a model to be imitated, especially in a heated context such as ours is increasingly becoming.

The first reading for today’s Mass appropriately appeals to “prudence” and “wisdom” as they are described in the Book of Wisdom. The lesson to be drawn is that we need to pray incessantly for the grace and the ability to imitate St. Robert Bellarmine.

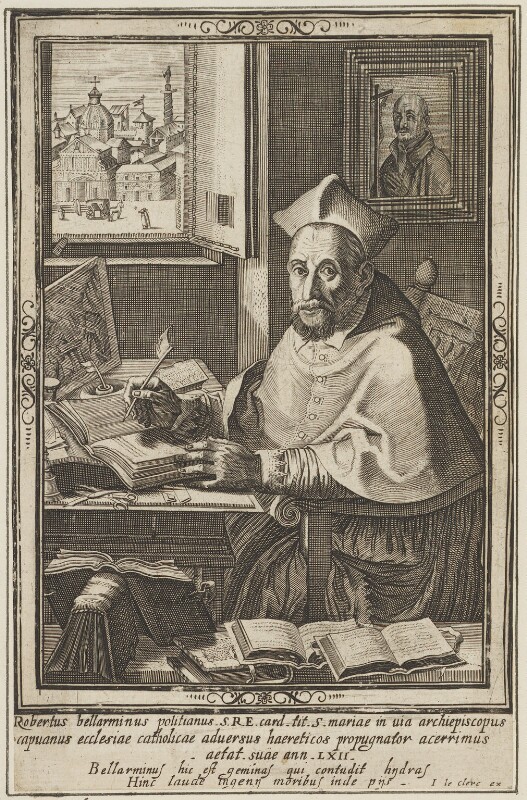

*Image: Robert Francis Romulus Bellarmine by an artist and date unknown [National Portrait Gallery, London]