Rock climbers usually go up in pairs. Both are clipped to a rope, which is affixed at intervals to the rock. The “lead climber” has a little free rope as he goes up, but never so much, one hopes, that if he slipped he’d get severely hurt by a long fall.

Because complete trust is essential to such climbing, partners can form one of the closest of human bonds. Only the brotherhood felt by soldiers in battle can rival it, they say. If we take life in general to be a struggle, not unlike a perilous mountain trek, then a climbing partnership can serve to represent true friendship. No wonder many Christians are drawn to climbing or reading stories about it.

In what is called “free soloing,” in which a single climber goes up “free,” that is, without any rope protection, and “solo,” that is, without the help of a mate, cooperation is unnecessary and indeed would only be a hindrance. Every amateur who attacks a boulder wall at the local rock gym is free soloing, but safely so, at small heights and over a mound of pads.

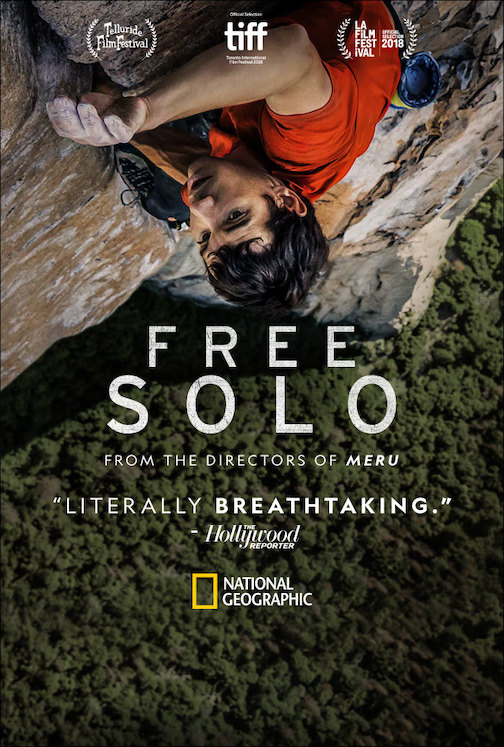

But a few really skilled climbers free solo at dangerous heights, where a mistake means death. The most skilled of these is Alex Honnold, known for his free-solo ascents up El Capitan in Yosemite. The National Geographic documentary about the latter climb, Free Solo, has just been made available for home viewing.

Free soloing is ethically controversial. But consider first its appeal. The climber can move faster, and so conserve strength better. It seems very pure: it’s just rock, sky, man. A successful ascent vividly proclaims its perfection: What could be a more supreme demonstration of mastery than someone, so reasonably confident of his complete control, that he regards his life as hardly at risk in the attempt?

Ethically, the spirit of the free-soloist seems highly admirable. It’s the old choice of Achilles: he’d rather die in the pursuit of perfection than keep himself alive doing something that seems mediocre. Didn’t Aristotle say we should prefer “living well” over “mere living”? Also, as Christians, we admire people who burn ships and bridges behind them. Newman taught, in fact, that we are not truly living as Christians if each day we are not risking our entire life on Christianity’s being true. (See his sermon, “Ventures of Faith.”)

We also look upon the achievements of an Alex Honnold with a proper pride for our shared humanity. He seems to place the human race at the pinnacle of nature. Not even a mountain goat could scamper up the Dawn Wall in Yosemite. (An insect could do so, but never would.) Honnold might truly have said at the top of his climb, “That’s one giant leap for mankind . . .” We need such sources of pride now more than ever. The green and crunchy folks won’t admit it, but this is a deep reason for Honnold’s popularity.

And then, among the human race, a free soloist seems to prove the reality of what Aristotle and St. Thomas called “godlike” virtue – a virtue so strong, that it exceeds ordinary human boundaries (just as there is a bestial depth of vice). Honnold surmounting a difficult overhang near the top of El Capitan, suspended 3000 feet over the valley floor below, strikes everyone as possessed of superhuman courage.

But free soloing is regarded at the same time as ethically fraught. Rock climbing, people say, is not a “serious” activity like warfare but “playful,” like recreation, sports, and entertainment. It’s not worthy, then, of anyone’s risking his life over it. Free soloing is as foolish in its way as the screwy golfer who tries to finish his round in a lightning storm. And even if the very greatest of free-solo feats are worth the risk of life, any other free-soloing attempt is clearly not, and the great feats, such as Honnold’s, if celebrated, will only encourage those others.

Readers who consider watching Free Solo should know that only the last 15 minutes covers Honnold’s famous ascent. The bulk of the film deals with his relationship with his girlfriend, who shacks up with him in his van. He treats her like a slightly annoying, monogamous groupie, while she clearly wants him to give up climbing and marry her.

This National Geographic climbing “documentary” apparently turned itself by necessity into a tedious reality TV show because, ironically, it was discovered in filming that it was just too difficult for Honnold to attain complete concentration with a 7-man camera team following him up the route. So they ended up with very little footage of the ascent, filmed at great distance through telephoto lenses.

Yet the girlfriend’s constant presence teaches, to the wise, some profound truths about love and marriage, such as: He does not love her more than climbing (that is, more than himself). Or, for him to commit to marrying her, would be the same as to commit to stopping climbing: and thus marriage is an institution which lifts us out of egoism. Or, as a matter of charity, celibacy is necessary for a way of life comparable to Honnold’s (think: priesthood).

But her presence also reveals something deeply troubling about free soloing’s appeal. If team climbing represents friendship, then free soloing must be taken to stand for a kind of autonomy that borders almost on autism. Honnold, raised by his mom after a divorce in a household where, he says, no one ever used the “L” word, must deliberately block out all affection for his girlfriend in order to succeed. He even asks her to leave the van in the days preceding his ascent.

I marvel at Honnold and others like him. But that makes me worried. My worry is that we marvel – our culture marvels – at free soloing, rather than finding it despicable, because we are a drawn to the ideal of autonomy, even a foolhardy autonomy, which risks everything for projects that have no value beyond being the creation of someone’s will.

*Image: El Capitan, Yosemite Valley by Albert Bierstadt, 1875 [Toledo Museum of Art, Toledo, OH]