A few years ago, I suggested that there is a strong resemblance between the Catholic idea of Purgatory and the Hindu idea of Reincarnation-plus-Karma. In a way, they are two varieties of the same basic idea: that the journey from this life to union with the divine is a long one, for almost all of us, even after death.

In reply to my suggestion, a learned Dominican argued that I was quite mistaken; that there is little or no similarity between the Catholic idea and the Hindu idea. In deference to my theological betters (I have considered Dominicans to be my theological betters ever since I was educated by them at Providence College ages ago), I dropped the comparison, and thought about it no further.

Apparently, however, I have been thinking about it, at least in the subconscious regions of my mind; for it recently popped up again, and seemed to me a thought worth pursuing since many people in the West are willing to entertain ideas from the East, while almost automatically dismissing the teachings of their own religious traditions. How many of our contemporaries, even Catholics, think about Purgatory these days?

The most obvious difference between the two ideas is that Hindus believe we are living our next life right here on the planet Earth, whereas Catholics believe our next life will be led elsewhere – though it is not at all clear where this “elsewhere” is. Purgatory is neither this present world or the fullness and transcendence of Heaven. What and where it is – assuming such categories apply to such an intermediate realm – is debated, and probably always will be, among quite respectable theologians.

Hindus believe further that the individual soul has pre-existed this current life, i.e., we lived in another body before our current body. And we lived in yet another body before that one. And so on and so on. Catholics don’t believe in pre-existence. We believe that our soul was individually and miraculously created by God at the moment that our body began as the result of natural reproduction. (“Clever” Catholics – more clever than I am – have been known to make a case that our current life is part of Purgatory.)

The obvious objection to the notion that we have lived before this lifetime is that we have no memories of a previous life. But believers in reincarnation reply that while we probably have no conscious memories of a previous life, we may have unconscious memories that help shape our current attitudes. Further, isn’t it possible that certain inborn skills – the kind of skills that are most obvious in geniuses like Shakespeare, Newton, and Mozart – may have been acquired in a previous lifetime?

Refuting that view is beyond the scope of the present column, but the thing that Hindus and Catholics agree on – something often overlooked in discussions of different religions – is that, although there may be a small number of exceptions, the ordinary human is not ready, is not worthy, at the moment of death to pass immediately to a state of ultimate beatitude, a state of union with the Godhead. A long state of purification will be needed before that will have been achieved.

Catholics have often in the past thought of Purgatory as a place of mere punishment, a place where we suffer for the sins we have committed. But the Catechism of the Catholic Church speaks of it, not as a place of mere punishment, but as a place of purification. (CCC, 1030-32)

Pain and suffering may indeed be an essential element of purification, but so is growth – growth in goodness, growth in holiness. We should think then of Purgatory as a place of improvement, a place of spiritual growth. When, after a hundred years or a thousand years or a million years, we have become sufficiently good and holy, we may then, but not before then, proceed to the Beatific Vision.

Protestants have usually had two objections to the Catholic idea of Purgatory. First, they say it’s non-Scriptural. Though it appears to be clearly implied in 2 Maccabees 12:46, where prayers for the dead are commended “that they may be loosed from sins.” Protestants generally regard the Maccabbee books as apocryphal, not Biblical. But if we count those two books as Biblical, which the Catholic Church does, then Purgatory has a solid Scriptural basis.

Second, Protestants see no need for us to make post-mortem atonement for our sins since Jesus made full atonement by his suffering and death. There is no need for prayers for the dead, since at the moment of death we go immediately either to Heaven, where we have no need of prayers, or to Hell, where they will do us no good.

Hence a phenomenon that seems odd to Catholics: when death takes place, the good Protestant prays, not for the person who died, but for his friends and family, living persons who suffer from this death.

If we see Purgatory not as a place of mere punishment (a penitentiary), but as a place of spiritual growth (a reformatory), this Protestant objection is met. But the question of the soul’s readiness for entry into Heaven remains.

There are profound differences, of course, between Hindu and Catholic ideas, and not only about the afterlife. But I think karma and Purgatory are related concepts from ancient spiritual traditions that shed some light on one another. I particularly think that Catholics at this moment in our history can gain a better understanding of Purgatory by contemplating that, as in other traditions, it offers a much richer view of our spiritual lives, even after death, than the superficial assumptions we find in our post-modern world.

The achievement of godlike goodness and holiness – which may well be the whole point of the universe (it may be that “one far-off divine event, to which the whole creation moves”) – requires that we travel a long and arduous road. No Protestant shortcuts.

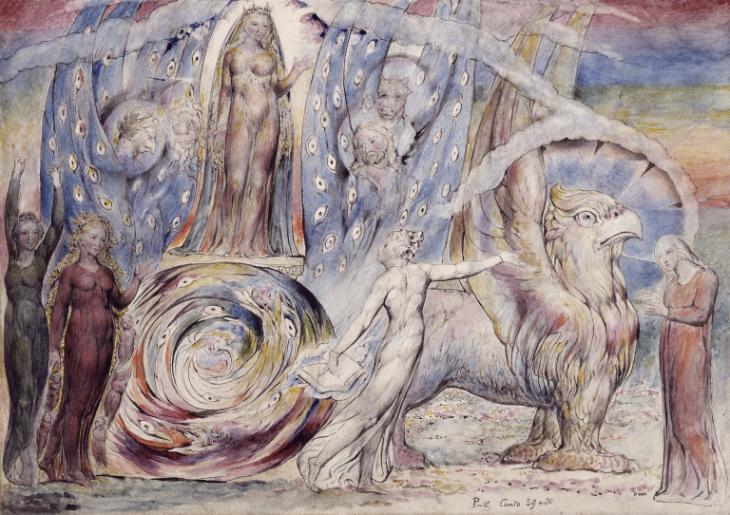

*Image: Purgatory, Canto 29 by William Blake, c. 1825 [The Tate, London]. “Beatrice Addressing Dante from the Car” is one of 100 watercolors Blake produced “during a fortnight’s illness in bed.” It was Beatrice who arranged for Virgil to guide Dante through Hell and Purgatory and she greets him as arrives in Paradise.