Over the course of his lifetime, John Henry Newman was many things: scholar, reformer, preacher, convert, theologian, priest, and cardinal. Through it all, however, he was an educator. Cor ad cor loquitur (“Heart speaks to heart”) was his motto, and he believed strongly that “personal influence” is the best means of teaching the truths of our Catholic faith.

“Speaking from heart to heart” was so much his manner that students at Oxford and later Dublin’s Catholic University would flock to hear his sermons. His guidance inspired the high-school boys at the Oratory School in Birmingham, England, including Hilaire Belloc. And Newman met personally with parents to forge genuine partnerships in the care of souls – an unusual practice at the time for English boarding schools.

The practical schoolmaster was also a great visionary, whose Idea of a University and University Sketches helped define the Catholic university at a time when education was splintering into diverse models and objectives. Amid many pastoral works, Newman also wrote numerous texts of devotion and theology on topics such as the Blessed Virgin Mary, development of doctrine, the role of the laity in the Church, and the nature of conscience.

It is extraordinary to find so many achievements in one man. And how do we reconcile the private Newman with the public intellectual, who eagerly battled “liberalism in religion”?

We might explain Newman’s integrity in his devotion to education – both the moral imperative of forming every person individually according to God’s plan and the educational objective of cultivating the intellect, so that a Catholic can recognize, share, and defend truth.

The Vatican chose Newman to establish a university in Dublin, and prominent English Catholics chose him to establish his Oratory School because Newman clearly had the vocation of an educator. He spoke eloquently to a culture beginning to slide into secularism; having seen the results, Newman’s lessons resound today.

It’s good to contemplate the constitution of a great saint, but it was the integrity of Catholic laypeople that most concerned Newman. His sermons, lectures, and writings were often driven, not by general musings on theology and theories of education, but instead by the very practical concerns of a shepherd tending his flock.

Newman looked to faithful Catholic education for the repair of the human person, which had been disintegrated by original sin. In his fascinating 1856 sermon at the University Church in Dublin, Newman lamented that we tend to focus on knowledge to the exclusion of morality – or conversely, on morality without regard for sound reasoning. Each person’s soul is subject to conflicting appeals of intellect, conscience, passion, and appetite, all “warring in his own breast” and each trying “to get possession of him.”

This, Newman argued, was not our original state. At creation, God’s grace “blended together” all of our human faculties, so that they “acted in common towards one end.” It was the Fall that confused the soul, and we have lived so long in this fragmented state that many people doubt whether the various human faculties can ever be reconciled. Thus society is divided into centers devoted to the mind, or the body, or secular pursuits, and we despair of the integral unity that our souls truly desire.

Newman, however, believed that integrity can be achieved by authentic formation in Christ and development of the intellect. The Church’s objective in education is “to reunite things which were in the beginning joined by God, and have been put asunder by man.”

Such a project, of course, cannot focus exclusively on accumulating information or even on cultivating the intellect. An integral formation of the person is ordered toward truth in all its aspects.

The integrity of schools and universities was also important to Newman. In his Idea of a University, he conceded that a university can be devoted to teaching and learning truth without ties to the Catholic Church. But the integrity of university education would be suspect, because it fails to acknowledge divinely revealed truth and the relevance of Christianity to all learning.

In practice, a secular university “cannot be what it professes, if there be a God,” Newman claimed. To exclude the truth of God from education diminishes an institution’s ability to teach truth. It especially interferes with moral formation, which is necessary to restore the integrity of young people.

A university that does not assent to the authority of the Church with regard to faith and morals is headed toward complete secularization – and the same is true of elementary and secondary schools:

It is not that you will at once reject Catholicism, but you will measure and proportion it by an earthly standard. You will throw its highest and most momentous disclosures into the background, you will deny its principles, explain away its doctrines, rearrange its precepts, and make light of its practices, even while you profess it.

Newman believed strongly in the personal witness and influence of teachers, especially for moral formation. He envisioned several tiers of influence at the Dublin university: lecturers, tutors to help guide students and teach the liberal arts, and house staff focused on the moral training and personal habits of about 20 students per residence. The Oratory School had a similar structure.

Newman looked after his students in prayer: “May I engage in them, remembering that I am a minister of Christ . . . remembering the worth of souls and that I shall have to answer for the opportunities given me of benefitting those who are under my care.” Here we see the heart of Newman as Catholic educator, cooperating with both the Church and parents to restore the human integrity of young people.

Likewise today, we can reach students’ hearts with the zeal that Newman showed for truth and the formation of young souls. By renewing the integrity of faithful Catholic education, we can help bring about the springtime of faith that Newman yearned for.

Blessed John Henry Cardinal Newman, ora pro nobis!

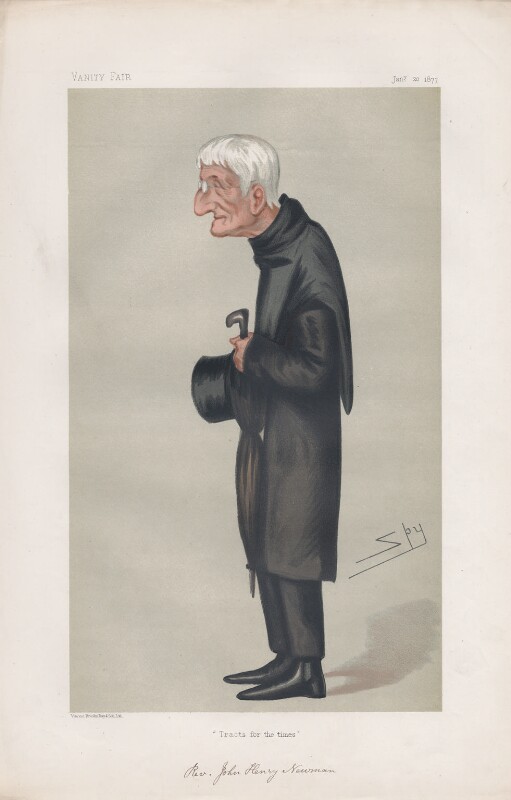

*Image: John Newman by Sir Leslie Ward, 1877 [National Portrait Gallery, London]. From the series Men of the Day No. 145, “Tracts for Our Times,” published in Vanity Fair (January 20, 1877)