One of the great pleasures of The Catholic Thing are the images that accompany every column every day: paintings that, as Bob Royal wrote in our inaugural column in 2008, demonstrate “the concrete historical reality of Catholicism. . .the richest cultural tradition in the world.” [Note from RR: The beautiful images in the columns we publish daily are the skillful work of Mr. Miner’s eye for beauty.]

And attentive readers will have noticed that no artist’s work has appeared here more often than J.J. Tissot’s – more than 100 times, in fact.

Jacques Joseph Tissot was born in 1836 in Nantes, near the confluence of France’s Erdre and Loire rivers. His father was in the drapery business, his mother designed hats, and young Jacques never wanted to be anything but an artist.

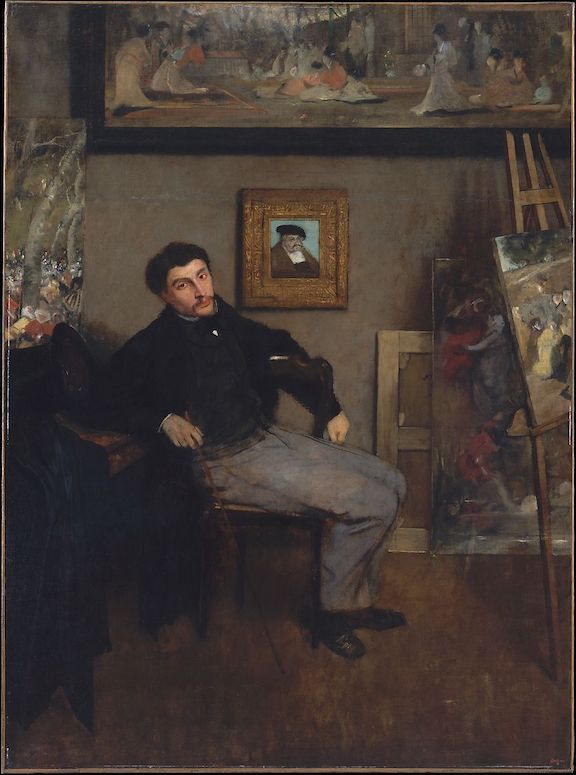

He went off to Paris at 19 and enrolled at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts. Among his friends were James McNeil Whistler, the American who painted a rather well-known picture of his mother, and the great French artist Edgar Degas, one of the founders of Impressionism. (Below: James-Jacques-Joseph Tissot by Edgar Degas, c.1867 [The MET, New York].)

Tissot quickly established himself as an accomplished, popular, and, therefore, financially successful painter of elegant Parisian society, which makes it somewhat surprising that he enlisted to fight in the Franco-Prussian war of 1870 and then got caught up in the revolutionary Paris Commune. Perhaps he was disillusioned by the war and joined the Commune in protest. For many then living, the Commune, which briefly seized control of Paris, was the continent-wide Revolution of 1848 redux. It certainly had Karl Marx himself celebrating what he considered a vanguard movement in an emerging “dictatorship of the proletariat.”

Whatever Tissot’s involvement was (and he was hardly a political radical), The Commune’s failure apparently caused him to flee to London in 1871, where he bought a house in St. John’s Wood. Perhaps because of what had happened in Paris, Tissot changed his first name from Jacques to James (some say his friend, Whistler, suggested it; others that Tissot had become a besotted Anglophile).

In that same London neighborhood lived a young Irish woman named Kate Newton (formally Kathleen Irene Ashburnham Kelly), an army officer’s daughter with a daughter of her own named Violet. Kate had been divorced by her husband after she’d confessed to being pregnant – an act of undeniable integrity on her part since she’d become with child before she and Dr. Isaac Newton had consummated their marriage. But Dr. Newton was understandably upset and “put her away.”

In any case, Tissot met Kate in 1875 and they began an affair. Shortly thereafter she gave birth to a son, Cecil George Newton Ashburnham (whom “everybody knew” to be Tissot’s son), and Kate and the children were fixtures at Tissot’s house/studio on Grove End Road.

She became his most-often painted model, his ravissante Irlandaise (“ravishing Irishwoman”). They never married, of course, both being Catholic. But he described their union as blissful. One sees that in his “The Garden Bench,” featuring Cecil, Kate, Violet, and another girl, probably a niece of Kate’s. (The Garden Bench, 1882 [private collection]):

But then Kate contracted tuberculosis (as, it would seem, did all Victorian mistresses), and as her health failed, both she and Tissot descended into depression. She could not bear to watch his heartbreak, and, on a day in 1882, she overdosed on laudanum, a nasty tincture of opium nicknamed the “mother’s helper.” Perhaps it was intentional – perhaps not. She was 28 when she died.

Tissot was inconsolable and sat by her body for four days – or that many hours, depending upon the account – after which he decamped to Paris. Alone. Does that mean he was a cad, leaving the children behind? Perhaps, although circumstantial evidence lately suggests the boy Cecil was not Tissot’s – that what “everybody knew” was, in fact, not true. (The two sustained a lifelong friendship.)

In Paris he began again to paint society women for willing patrons, and one such commission took the still-grieving painter to the Latin Quarter’s Church of Saint-Sulpice. At one of his working visits there – during priest’s elevation of the Host – Tissot had a vision of Christ. The Lord’s body was bloodied but luminous, and He was comforting two homeless people in the midst of a ruined building, probably a crumbling church – a very Franciscan moment, and one that changed Tissot’s life. He did a painting almost immediately after this epiphany called Inner Voices: Christ Consoling the Wanderers (now at the Hermitage in St. Petersburg, Russia):

But this was only the beginning.

As a now devout Catholic wishing to devote his art to celebrating the life of our Savior, Tissot traveled to the Middle East several times to look at the land where Jesus had walked and look into the faces of the ancestors of those who had proclaimed Him the Christ.

You may recall last year’s Good Friday column here, “The Scriptural Stations of the Cross,” which presented the fourteen Stations, from Gethsemane to the Entombment, illustrated with watercolors from Tissot’s monumental series, The Life of Our Lord Jesus Christ. He did hundreds of paintings based on what he saw in the Holy Land, most of which are now in the collection of the Brooklyn Museum, acquired through “subscription” and by popular demand in 1900. Sad to say, although the museum mounted a limited exhibition of the series in 2009, most of Tissot’s magnum opus is now in storage.

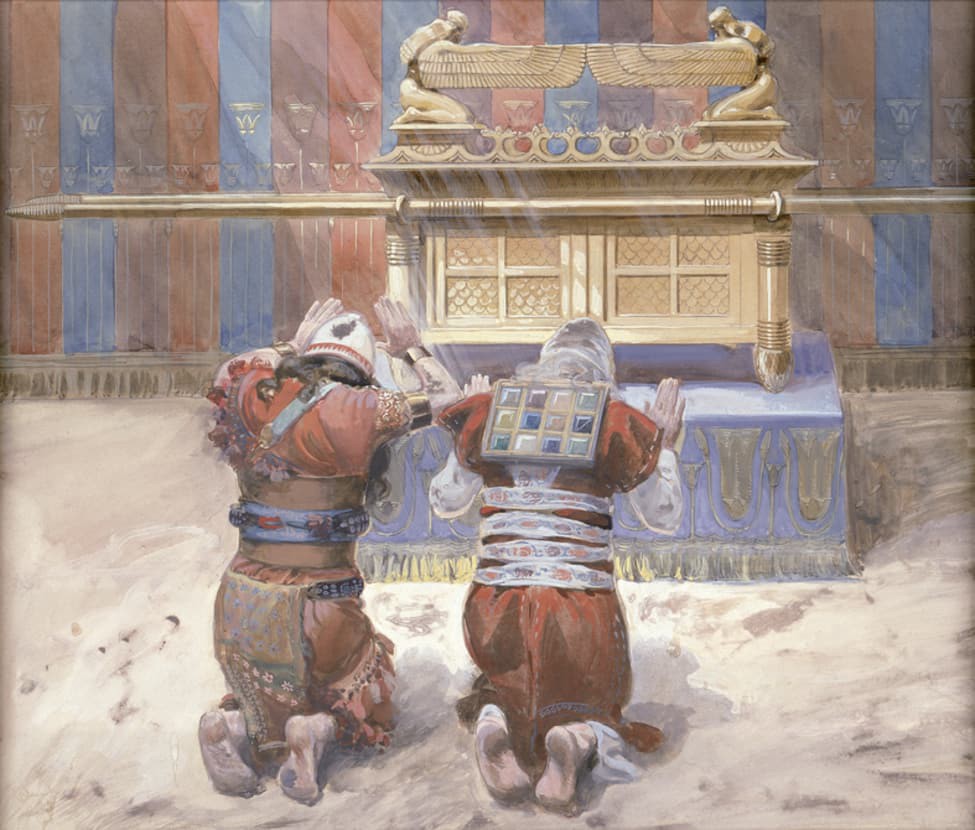

(Above: Moses and Joshua in the Tabernacle by J.J. Tissot, c. 1900 [Jewish Museum])

Before the good people in Brooklyn acquired his Christian paintings, they had gone on a popular tour of the U.S. – and been published in expensive books and reproductions – and this success motivated Tissot to turn his attention to the Hebrew Scriptures – again, in an astonishing outpouring of artistic achievement, aided by a studio staff before and after Tissot’s death in 1902. And that second series of 368 watercolors was, in a roundabout way, acquired by New York’s Jewish Museum and very appropriately so.

All in all, it’s an amazing record of the fruits of a return to the faith. I know of no other artist who created a more extensive body of work devoted to the Judeo-Christian Biblical tradition.