Many people assume that a society “progressive” in its moral views would naturally be “progressive” in its economy, that someone who believes in a more equal distribution of goods would also be a person who believes in more permissive standards of behavior.

I am not denying the perception, but the reality is often the reverse of what young progressives seem to assume. Those who wish to ensure goals such as a more equitable distribution of the wealth in the economy and a greater respect for the environment are demanding considerable self-discipline of the sort we do not customarily or habitually demand of people in a culture of lifestyle libertinism.

You think it unreasonable to ask a man to discipline his appetite for sex, but then you think it eminently reasonable to require him to relinquish his appetite for money, status, and power?

It’s odd to say, “You needn’t have the discipline to stay faithful to your wife and children,” but then insist that someone should be responsible to all humanity for recycling his plastic containers. If a man can’t discipline his appetites enough to remain faithful to his own children and to the wife to whom he pledged lifelong fidelity before God, what makes anyone imagine he would discipline himself enough to remain faithful to the generations after his death? It should be no surprise, then, that as societies become more “progressive” morally, they rack up progressively more debts for future generations to pay.

The permissiveness “progressives” support in the realm of personal morals is simply another species of the autonomous individualism they wish to combat in the economic realm. And every weakening of the social bonds of society, especially those developed in the selfless bonds of marriage and family, results in a lessening of the social capital needed to ensure that people remain willing to share plentifully with others without fear of being left indigent themselves.

When people build greater levels of social trust, they are more willing to share. When they fear that even their closest relationships are based on no more than the other person’s pleasure or self-fulfillment, this willingness drains away and people become self-protective. When this happens, the only way to ensure even minimal forms of cooperation is by means of coercive governmental control. Is this really desirable?

If you don’t want the government intruding into your private life, would it really surprise you to discover that the guy next door doesn’t want the government intruding into his private business decisions? If you want to use the coercive powers of government to force a doctor to perform your abortion, would it really surprise you if you found that your landlord was eager to use the coercive powers of government to evict you for not paying your rent?

By the same token, if you insist the government has no business telling you how much to pay your workers and if you want to use the coercive powers of government to favor your business, don’t be surprised if “progressives” resist government intrusion for the things they like and encourage it for the things they don’t.

In a culture in which freedom means primarily freedom from constraint, freedom to do whatever I choose, not freedom to devote myself to the good and the welfare of others, it quickly becomes clear to young people that the freedom they are being “sold” every day by the cultural elites – the freedom of autonomous self-creation, the freedom to create an identity with consumer items, the freedom to pursue what is exciting and to live like the celebrities in the ads – costs money, and lots of it.

The “artsy” life in New York City is expensive. The McMansion and the expensive prep schools are expensive. Studies have shown that over a quarter of the people making over $100,000 a year say they are “just barely making it” and cannot afford their basic needs. Self-creating autonomous freedom costs money; celebrity lifestyles aren’t cheap.

L.A. and New York may be hotbeds of voters for socialist causes, but they are far from being moral exemplars of income equality. People living in expensive houses and apartments who spend money on bars and clubs, but want the government to “do more for the poor,” have very little credibility.

Move out of the expensive New York City apartment, live in a modest city and simple neighborhood, send your kids to the local public schools or to a modest Catholic school that actually serves the poor, and you might have some “street cred.” Otherwise, you’re just a poseur. You cannot say, “You people give up the gross things you enjoy while I keep the sophisticated pleasures I enjoy.”

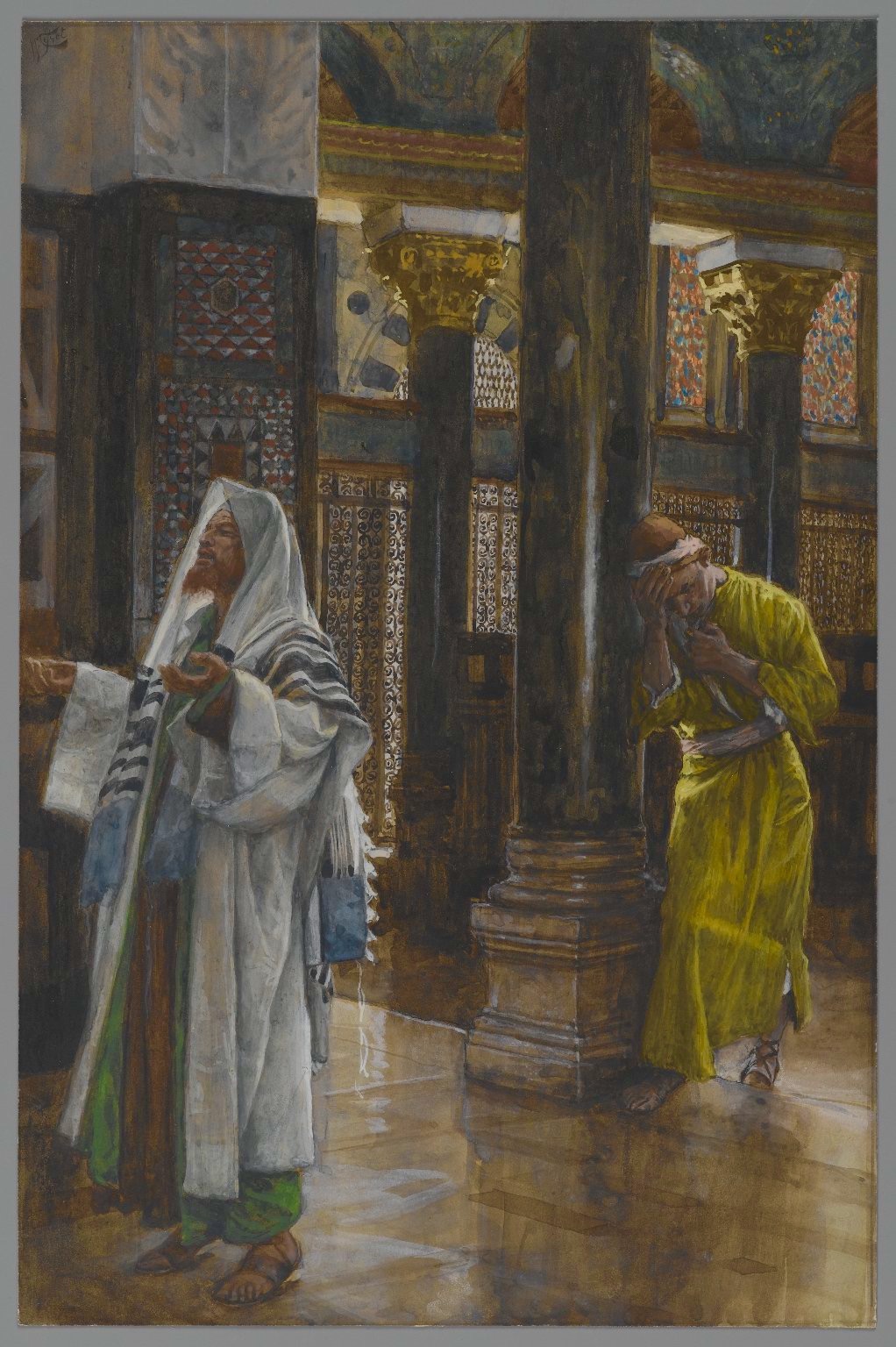

Lifestyle liberals will never be able to secure social justice if they wear their concern for social justice like the Scribes and Pharisees used to wear their religious garments: as a sign of personal self-righteousness. “They “broaden their phylacteries and lengthen their tassels”; “all their deeds are done for men to see”; when they propose giving to the needy, they sound a trumpet for others to respect them – as self-proclaimed “Pope Francis Catholics” perhaps?

Too many Americans, whether self-proclaimed “liberals” or “conservatives,” believe that what makes America great is that individuals get to choose their own idea of the good, untethered to the claims or needs of others, and then get it – as a right divorced from any obligations to others or to the common good.

Both “laissez-faire conservatives” and “progressives” are called upon to realize that America will only be “great” when we can make our own the prayers of the too-often unsung and unheeded verses of “America the Beautiful”:

America! America!

God mend thine every flaw,

Confirm thy soul in self-control,

Thy liberty in law!

America! America!

May God thy gold refine

Till all success be nobleness

And every gain divine!

America! America!

God shed his grace on thee

Till selfish gain no longer stain

The banner of the free!

*Image: The Pharisee and the Publican (Le pharisien et le publicain) by James Tissot, c. 1890 [Brooklyn Museum]. See Luke 18:9-14 (“God, I thank you that I am not like other people . . .”)