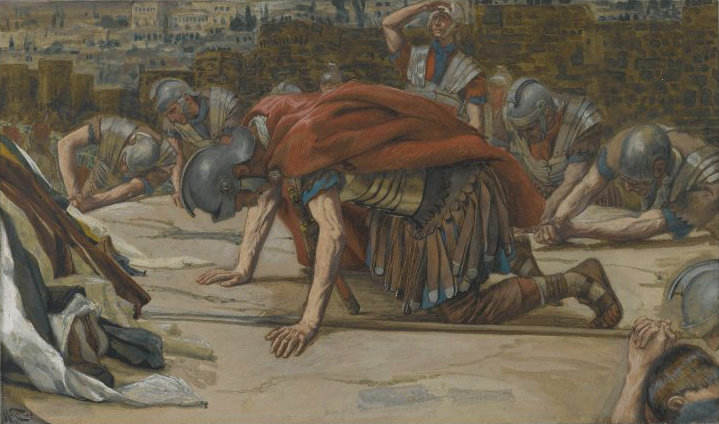

One of the strangest lines in the Gospels is uttered by the centurion at the foot of the Cross. In Mark, we are told that when he saw that Jesus had “breathed his last,” he said: “Truly this man was the Son of God.” (15:39)

One would have thought this was the last thing a person would say after seeing a man die. Everyone knows that the one thing gods don’t do is die. Thus, it would have made more sense if, the moment the centurion saw Jesus die, he had said: “Well, clearly that guy wasn’t a god.”

Had Jesus shot fifty feet up in the air and shot laser beams out of his eyes, then we might imagine the centurion saying, “Uh oh, that was the son of God.” After which, he might have run for cover, reasoning that the man, now so revealed, would not be entirely pleased with those who treated him so badly — what with the whole spitting, taunting, scourging, crowning with thorns, and nailing him to the Cross business.

But Christ didn’t shoot fifty feet in the air and shoot laser beams out of his eyes. That’s comic book stuff. No, He died: something “gods” are never supposed to do. And yet it was at that moment the centurion said: “Truly, this man was the Son of God.”

We have to imagine that Mark included this odd story in his Gospel, well, first, because it happened. It would be a strange thing to include it if it hadn’t, since most readers would be inclined to conclude, as I did, that it made little sense for a down-to-earth Roman soldier to conclude from a man’s death that He was “the son of God.”

But second, Mark likely included the story because it represented something important about the faith of the early Church. The apostles weren’t proclaiming the divinity of Christ in spite of His death on the Cross, but because of it. They weren’t hiding the fact of Christ’s death; rather, they were proclaiming that, contrary to what anyone would imagine, His death on the Cross was the decisive revelation of his divinity and His role as our divine Redeemer.

This is so strange; it really should give us pause. A God who dies? What kind of God is that? Either a powerless one, or a really, really devoted one. But if He is that devoted, and if He can undergo death – not avoid it, not pretend it, but really undergo it – and still beat it, then He has fundamentally altered our entire idea of what it means to be “powerful.” A power so great that it transcends even death, but then submits itself to death? A God who reveals Himself as a servant? We don’t sacrifice to Him; He sacrifices Himself for us? It bursts all our categories.

And if it were, how would God communicate that truth to us? Lighting storms? Earthquakes? Beautiful sunsets? We have those, but for many of us, “we had the experience but missed the meaning.” But death – now that’s something whose meaning is hard to miss. Or perhaps it would be more accurate to say, its looming presence threatens whatever meaning we might have thought we had.

Consider the situation of Kate Middleton, Princess of Wales. Those of us who have had a cancer diagnosis, as she has, know that it changes everything. The future becomes uncertain. The plans one had made for next week, next month, and next year become irrelevant. As a mother, she is undoubtedly worried about her children. Her struggles are not more important, just more public. But the questions are the same. Is there any meaningful future for me at all? It’s excruciating – like a cross.

Faced with the darkness of death, the fundamental questions of life are posed with remorseless urgency: What could overcome an uncertainty so great and a darkness seemingly so complete? Could anything restore light and peace and set life on a surer, less precarious foundation?

We can’t heal the universe. But maybe its Creator can. But if He were to heal it, how would He do that? Laser beams? Light shows? Those are silly magic tricks. Or would it have to be by imparting a love so great that it illuminates the darkness?

If this were “A Charlie Brown Easter,” and Charlie Brown cried out: “Does anyone know what Easter is all about?” Linus might step forward and say, “Yes, Charlie Brown, I know what Easter is all about.”

God so loved the world that He gave His only Son. Because there is no greater love than this, that man should lay down His life for His friends. And the “good news” is that no power on the earth, above the earth, or below the earth, can separate us from that love and from those we love. And if that’s true, then the universe isn’t empty and meaningless and human life isn’t empty and meaningless, even in the face of suffering and death.

If someone loved you so much that he had been willing, freely, to sacrifice his life for you, would it change the way you live? Would the revelation that you were loved that much make you think differently about your worth and the meaningfulness of your life? That much love and devotion – for me? It’s almost too much to believe. But why fight spring? If that’s the universe God has made, and if He wanted to share His love with us that much, why say no?