A disturbing 2019 Pew survey found that only a third of Catholics believe that the Eucharist is truly the Body and Blood of Christ.

The results of such surveys, of course, depend on what questions were asked and to whom. So, for example, if people were asked, “Do you believe in transubstantiation?” some might have had the same reaction I did when I was challenged recently whether I believed in “impanation.”

What the heck is impanation? I looked it up. “Impanation,” as it turns out, is the claim that Christ is “in” the bread and wine, but it’s still bread and wine. (The “pan” part refers to “bread.”) So no, I do not accept “impanation.” It could have been something innocent, but it isn’t. And I wasn’t going to agree to it until I understood it.

Someone thought I was guilty of impanation because I had written that Christ was “truly present in the bread and wine.” My focus was on His being “truly present.” But strictly speaking, it is no longer bread and wine; it is the Body and Blood of Christ. It would make no sense to say that the Body and Blood of Christ are “truly present” in the Body and Blood of Christ. So as a shorthand, we say that Christ is present in the bread and wine.

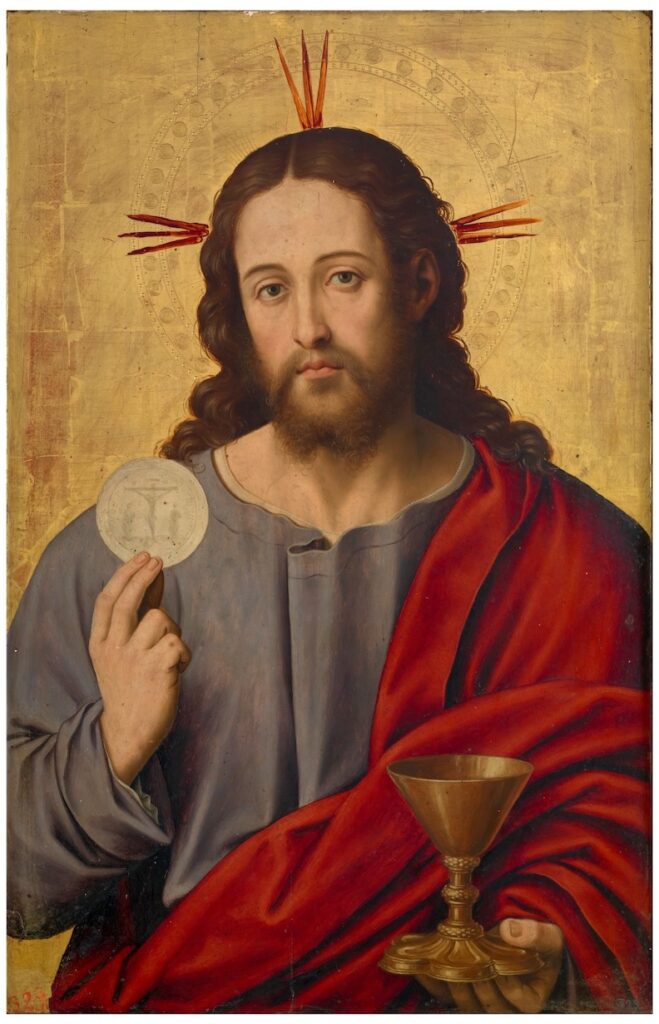

A young woman once said to me, “I could never be Catholic because I just can’t accept the doctrine of transubstantiation.” “Wait,” I said. “Let’s take a step back.” The doctrine of transubstantiation was an attempt to describe the “Real Presence” of Christ in the Eucharist using the categories of medieval physics. The substance is now the Body and Blood of Christ, but the accidents of bread and wine remain.

But the point of that doctrine is to express what it means to say that Christ is really present in the bread and wine – or what used to be bread and wine and still looks like bread and wine, but is now, in substance the Body and Blood of Christ. “Transubstantiation” may sound dodgy, but it actually makes a lot of sense.

My friend made the usual reply. “Well, I believe He is spiritually present.” “No, hold on,” I said. “That’s not being really present. In the early Church, they clearly affirmed their belief that Christ was really present in the Eucharist, as present as He was during life and as present as He was when He rose from the dead.”

That was not easy to accept then, and it’s not easy to accept now. It’s why many left Christ when He insisted “You must eat my flesh and drink my blood,” an abandonment that would be hard to imagine if he had meant that you need only do this spiritually. I mean, he could have said, “Wait, I don’t mean my actual body and blood; that’s just gross. No, I mean this symbolically, metaphorically.” That, presumably, would have solved the problem nicely. But that’s not what happened.

“So, let’s work backward,” I said. “Do you believe that Christ lives, that He truly conquered death and was raised from the dead? Or do you think that He is only symbolically still alive – like “alive in our hearts”? “No,” she said, “I believe that Christ rose from the dead and ascended to the right hand of the Father. I say it in the Creed every Sunday at church.”

“Okay, do you believe that Christ really rose bodily from the dead, so that the Apostle Thomas could probe the nail marks on his hands and the spear wound in his side? Or was Christ ‘present’ in the room only metaphorically, because they remembered Him in love, or something of that sort?” No, she would not accept this thin gruel of “symbolically” or “metaphorically” present to the Apostles.

“So if you believe God really became Incarnate, and if you believe that Jesus Christ was God Incarnate, the Word made flesh; and if you believe that Christ truly rose from the dead, not merely ‘spiritually’ or ‘metaphorically,’ but really, as a unity of body and soul; and if you know that this was the faith of the Apostles and the early Church; and if you recognize that the doctrine of “transubstantiation” was an honest attempt to describe the Church’s belief that Christ is truly present in the Eucharist, but when we consume it we’re not chomping on His bones, because although it is now the Body and Blood of Christ, it still has the properties, the “accidents,” of bread and wine; would that help put this odd word ‘transubstantiation’ into its proper context?”

But the further, existential question is this: Was Jesus God incarnate? And do I believe that God loves sinful humanity so much that He would really “empty Himself of His divinity” and embrace our humanity and then sacrifice Himself for us on the Cross?

Because (a) that’s what consuming the Eucharist means: it is our embodied, sacramental participation in Christ’s sacrifice, and (b) if you can believe all that business about God and God’s love being so great that He became man, dwelt among us, and died for the forgiveness of our sins and the restoration of our communion with God, then it seems odd to insist that God can’t be present in the Eucharist.

God created every atom of the universe, did all those amazing things, but He can’t, or won’t, make Himself continually present to us in an embodied way in the Eucharist?

So, be honest, is “transubstantiation” really the problem? Or belief in a Creator God who can love us so much He became man and died on the Cross? It is understandable why that would be difficult to accept. But just so we’re clear: that’s what the “Good News” is.

Oh, and in case you’re worried, that friend has been Catholic for years now. Seems transubstantiation wasn’t as much of a problem as she thought.