The third part of the Ordinary of the Mass is the Credo. I sometimes wonder whether we regard it, rather, as the Credo et Exspecto. Because it consists not solely of acts of faith but also acts of hope: “Additionally, I await the resurrection of the dead, and the life of the world to come.”

In the grittier language of the Apostle’s Creed, it’s the carnis resurrectionem that awaits, the “rising again of our very flesh” – a scandal since the beginning of the Church to all who attempt to intellectualize or spiritualize away the full Christian hope.

Why is this concrete hope so important for us today? Two reasons, I think. The first, obvious to some but not, alas, for most of us most of the time, is the promise of bodily integrity and beauty. The lame, the maimed, the blind, the disfigured, those whose flesh was rotting off their bones from leprosy: these are infirmities which are ugly as well as distressing. Our Lord’s pity, and even anger at the consequences of sin (see Jn 11:33), were directed it seems chiefly at these kinds of suffering – his divine compassion corresponds to the belief about the resurrection of the body.

These infirmities, we believe with confidence, will not simply be removed at death but ultimately answered and made whole. Thus, those of us who right now do not suffer from like infirmities can show real solidarity with those who do, not simply through our prayers for them, but also by aligning our hopes with theirs, to our own spiritual benefit.

But the second reason why this Exspecto is so important for us today is that it is a remedy to a certain, let us say, “Protestantization” of Catholic faith, which surely looms as a significant distortion, especially in the United States.

Please do not misunderstand me. In no way do I wish to denigrate my Protestant brethren for their love of prayer, enthusiasm for worship, clarity about the priority of divine over human authority, and deep love of the Scriptures. In all of these dimensions, Catholics can and should imitate their zeal. I mean specifically the subtle and long-term effects of Luther’s teaching of justification by faith alone, sola fide.

And I should better say “Luther’s teaching in some of its common influences.” Some great theologians, including St. John Henry Newman, have held that Luther’s teaching, when precisely and properly understood, coincides closely with Catholic principles.

The problem is that it’s difficult to receive in its precise and proper sense. Speaking from experience, from when I was a Protestant, I know that a common effect of this teaching is to soften or even remove what I like to call the ordinary operation of “effective practical reasoning” from the Christian life.

By “effective practical reasoning” I mean how we deliberate and act when we want to achieve something practical, for example, when we plan on a career, start a business, invest money, or act as a fiduciary or steward on behalf of someone’s concrete interests.

Such practical reasoning involves:

• deliberating about goals;

• choosing the most valuable and practicable goal among them, for me;

• taking effective steps to achieve those goals, of a means-end character; and

• regularly exercising some process of accounting, measurement, and self-examination, to keep ourselves honest and make any necessary corrections.

Think again about how someone proceeds when starting a business or, say, training to become a top athlete.

But if salvation is a matter of faith alone, not works – if undertaking practical means toward an end might seem to express a lack of faith, or even a servile fear – then what is there to do in the Christian life? It looks like Christianity will become mainly a matter of prayer, study, and the cultivation of certain wholesome subjective attitudes.

Yes, charitable works towards others can be conceived of as an outflow or “fruit” of these. But what room is left for the canny, effective, and practical advancement of one’s own long-term spiritual interests? The latter will easily be dismissed as “egoism” in contrast to the solely Christian “altruism.”

My point is that, in contrast, “I await the resurrection of the dead and life of the world to come” establishes a definite and concrete goal, and it teaches us implicitly that we should live with that goal before us.

To take a very elementary point, consider the question, “Should I act so as to save my soul, attain heaven, and achieve a higher degree of glory in heaven if possible?” Historically, Catholics would have replied, without hesitation, “You’d be a fool not to.” But you will find many Catholics today holding that to act to attain heaven is a base motive, because it looks for a reward. Yet this is the same as to say that, in the Christian life, we should not use effective practical reason to aim for goals.

I am struck by how the saints act differently, in their industry, diligence, and eminent practicality. St Thérèse of Lisieux when she was a child carried a string of beads in her pocket to multiply and keep track of her good works throughout the day, as if challenging herself, “How many can I do?”

St. Theresa of Avila, whose memorial we honor on Friday, is candid about her motives for taking the habit: “The trials and distresses of being a nun could not be greater than those of purgatory. . . .It would not be a great matter to spend my life as though I were in purgatory, if afterwards I were to go straight to Heaven, which is what I desired.”

Undeniably Christian practicality is itself a mystery. St. Theresa admits her calculation was apparently based “more on servile fear than on love.” But she goes on to explain that many decisions in her life have had this character. God regularly “forces her to use force against herself.” And invariably, when he does, he rewards her later, for acting despite her fears, with inflowing graces and the greatest tenderness.

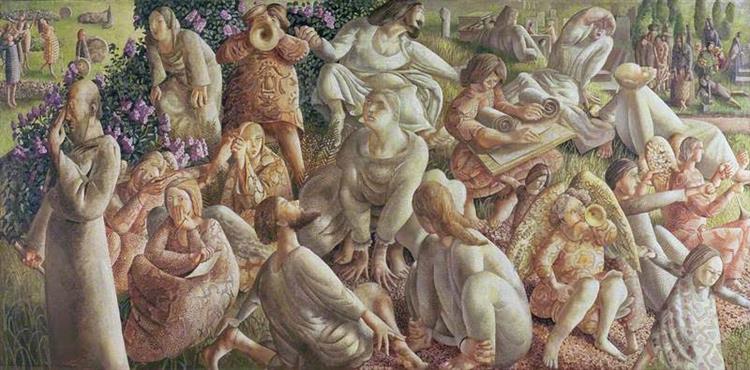

*Image: Resurrection: The Hill of Zion 1946 Stanley Spencer [Harris Museum & Art Gallery, Preston, England]. “Christ, seated at the top, is trying to organise his rather chaotic disciples and angels. Around them people stretch and yawn as they rise from their graves.”

You may also enjoy:

Fr. Thomas G. Weinandy’s Those Dead Dogmas

Dr. Elizabeth A. Mitchell’s She Is Only Asleep