No one can know how glad I am to find

On any sheet the least display of mind.(Robert Frost, “A Considerable Speck”)

“In the beginning was the Word. . .and the Word became flesh and dwelt among us.”

Divine revelation, I tell my students, is not simply the revelation of information; it is the revelation of a person. It is a self-communication of God inviting us into communion with Him.

So, for example, when a young man goes into a coffee shop and says to a young woman, “Hi, I’m Dave!” if she responds, “Yes, you’re Dave. Will there be a quiz?” she mistakes the self-communication of a person for a mere communication of information.

Dave’s goal differs from a science professor’s, who tells his class, “This is a highly toxic chemical; don’t get it on you.” That is a communication of information. The professor wants the students to respond, “Yes, I hear you; I get it.”

But when our young man says, “Hi, I’m Dave,” he is inviting the other person to respond in kind – not, “Yes, I hear you; I get it,” but “Hi Dave, my name is Kate.” The information is not unimportant, but it is not the only thing being communicated.

I mention this to suggest that, on the model of divine revelation, we should envision all human communication as a self-communication that invites others into communion. Thus the tragedy of plagiarism, of simply going online and copying things, is that what’s missing is you.

We think in words, so although we sometimes have the sense that “I know it, I just don’t have the words,” you probably don’t really know it. You may have a glimmering of a thought, but without the words, it’s just a ghost. You need to “in-flesh” that thought in actual words. And engaging in that hard work of making words clarifies the thought. Writing is a way of thinking, so when the words aren’t your words, then you haven’t done the hard task of thinking.

This brings us to the current fascination with ChatGPT, the robot that writes things for you. Some people love it, others hate it. What should we say about it?

A college administrator recently sent out a message to the campus composed by ChatGPT. When this was discovered, he had to apologize. And yet, given the impersonality of most communications from institutional bureaucrats, a robot might as well have written it. Nearly all messages from administrators are robotic. This is why no one reads them; there is no real communication. The only reason ChatGPT has become a thing is because so much that passes for communication today isn’t communicating anything – often not even information, which would have to be contextualized to become meaningful.

In an episode of the television series Westworld, a man gets a call from a company where he has applied for a job. The voice on the phone goes through the normal patter about “thanks, but we’ve decided to go with someone else.” The voice responds kindly to a few of his questions. But then, at a certain point, he senses something and asks: “I’m sorry, I don’t mean to be rude, but are you a human being?” The call hangs up.

Was it a robot or not? We never know. Would it have mattered? If robots replaced administrators, would anyone notice? A colleague suggests we get ChatGPT to write our assessment reports. Would they notice?

Since so much writing done these days is robotic, much of it could be done by a robot. That’s sad, but when your educational system spends all its time training dutiful bureaucrats on spreadsheets and little or no time reading beautiful English prose, then this is the result: people without words mouthing gibberish largely empty of thought.

The great parody of the ChatGPT culture can be found in a recent episode of the sophomoric comedy South Park. Some students are using ChatGPT to write their papers. When their teacher finds out, instead of being angry, he is ecstatic because now he can get ChatGPT to write the comments on his student papers, so he doesn’t have to read them.

A robot is writing the papers, a robot is commenting on them, no humans are involved. So why do it? Wouldn’t it be better not to perpetuate the illusion of education? Except schools indulge this illusion all the time. So I suppose ChatGPT is the appropriate tool for the culture we’ve created.

Also in this episode, young Wendy complains to her boyfriend Stan that he doesn’t respond to her texts quickly and thoughtfully the way one of her friend’s boyfriends does. When Stan checks with this young man, “How do you do this?” he is told, “ChatGPT.” He just inputs the text into the system and posts the response. Stan is reticent at first, but he can’t resist the social pressure.

Soon, he is posting ChatGPT responses without even looking at his phone. Unfortunately, Wendy has been sharing serious things with him in texts he hasn’t read. ChatGPT has been responding, and since it is designed to please the person inputting the information, she has been getting very sympathetic messages about her problem, just not from him. He has no idea what she has been sharing, but he can’t let her know.

This is the odd, unspoken reality about ChatGPT: its role must remain hidden for it to work. The illusion of the human element must be preserved or people are offended.

ChatGPT is a sad illusion of human communication that connects no one, just as modern social media produces an illusion of reasoned argument. Mutual brainless denunciation is not argument. But given these recent developments, I propose that we let ChatGPT produce all our reports, write and respond to our emails, and argue with other ChatGPT robots on social media.

Thus liberated from foolish wastes of our time, we human beings can have lunch together and talk about real things that matter.

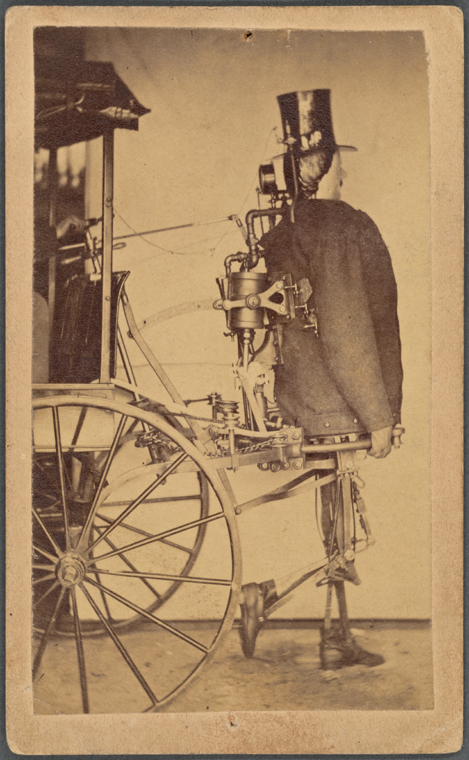

*Image: Steam Man by an unknown photographer, 1868. [A steam-powered vehicle created by American inventors Zadoc P. Dederick and Isaac Grass]

You may also enjoy:

David Warren’s Too Big to Succeed

Ashley E. McGuire’s Big Girl Pants