This will be the confession of an artsie; both the confession of a crime, and a confession of faith.

I am, as many other people are, something of an artist. We aren’t all recognized as “great artists,” of course — consider the potential of an auto mechanic — but we make our income, or occupy our leisure, in making or otherwise preparing things.

A tiny minority of us pass the publicity standard for inclusion in the annals of the “fine arts,” but let’s not be classist or elitist, for the moment. Let us just consider artists in general.

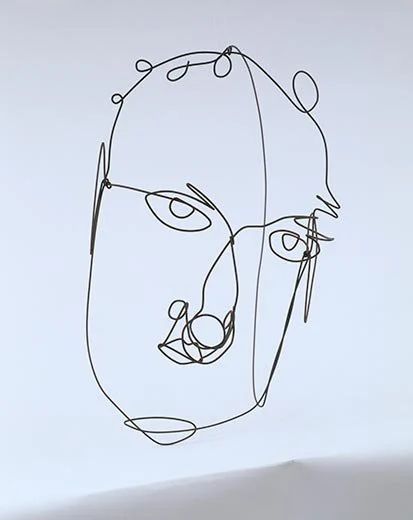

I was born that way, or rather, I was born to an artsie father, who had an artsie-loving wife. Indeed, as mama liked to explain (and I have seen photographic proof), I was brought home from a municipal hospital, and put in a freshly-painted crib. A Calder “mobile” (I assume a reproduction) was strung in the air above this crib, dangling just out of my reach. It was papa’s first essay in the modern “education through art” pedagogy.

Who knows whether it “took.” For while I have been a secret draughtsman, and invisible Sunday painter. I have never fallen for kinetic art. My desire for art has always exceeded my desire for journalism, true enough, but the lack of talent has determined my employment as a common hack.

My father, on the other hand, was a secret Christian. He had immense respect for chapels and for the Church at large, but mostly this was for her material culture: that is, for the art. Beauty was the portal that he tried to open for me, from the day I came home; yet not consciously from any religious motive.

His further beliefs were kept “subtle,” partly to avoid chastisement in these progressive times. But hidden or not, Christianity was there. (He gave me once a child’s “Life of Christ,” and told me not to let my mother catch me reading it. This was perhaps an exercise in “Platonic irony.”)

Another clue came from his dismissal of false religion. When companions revealed their “adoration” of Bach, or Picasso, he appeared strangely troubled by the display. He told me once that worship is for God, not for “handicrafts.” And always, “God is in the details.”

This was something that stuck, as I think Alexander Calder may not have. Though to be fair, my longstanding exhilaration with fine effects of color and shading may have been acquired in the crib, since when I have been immediately arrested by any composition that deploys them knowingly (whether or not it moves).

Indeed, I have come to look upon the harmonies in painting and in music as contributing to the unanswerable proofs of God — “quietly startling” as they emerge in our world, oftentimes in art, and oftentimes outside of any artistic intention.

But I am slightly uncomfortable in museums. Papa would sometimes call attention to the “cultic hush,” and silence that prevailed in them (in the days before the main galleries of museums were wired for sound like airports). Usually, however, even polite discussion — except by a lecturer delivering an art homily in the posture of a priest — is discouraged.

Museums, the beneficiaries of extravagant public expenditure and the best work of our “starchitects,” have, after all, replaced cathedrals in urban life (while skyscrapers supply the otherworldly towers). Little museums are available as little retreats — as “holy” places where peace and quiet may be sought by those in urgent need of meditation, and prayer.

Well, many institutions have replaced the Church, in one or another of her aspects. I spot parodies of Christian religion everywhere. For instance, professional sporting and mass entertainments draw the people out for pseudo-religious inspiration; though I think that where they are cheering for rival sides, it is more of a simulation of gladiatorial encounters.

Rock concerts, instead, recreate the thrill of unity. They reproduce the throb of life, around a focal point in ritual music and tribal dance.

But these are not accepted as another religion, the way “science” is presented as the rational alternative to religious belief — and has been the several centuries now. For “science” is too simple an alternative, to consistently occupy the popular mind. The older religions had, in every one of their forms, aesthetic, ethical, and metaphysical dimensions that the latest “new atheists” can’t quite provide.

Yet beyond the reach of the conventional, new religions are forming that might eventually supply these missing parts. One of them is new vistas in the arts, detached from their ancient cultural role, and put forward as ends in themselves.

Plato, by the way, warned against this. He notoriously diminished poetry and painting, as mere imitations of the natural world — only copies of copies. This, of course, is a smearing simplification of what he wrote. To begin to actually understand him, we must begin to appreciate the dramatic and musical skills that were necessary to the moral development he was commending. They were religious.

Plato’s very emphasis on censorship of cultural activities was the mark of his sincerity, and of the vivid honesty of his proposed “republic.” For art is taught as the means to what we would call religion, and the people would be serious in his ideal commonwealth. To give “art” some independent authority, would be to invite bad inspiration. Inspire the good, instead.

Plato is, as his more attentive readers have discerned, more in touch with the “poetic” or “aesthetic” or “artistic” than philosophers have since been, and he shows how “education through art” should proceed.

The product of this education — the natural human, to be matured — is predisposed to this education. His misfortune is to have the scheme of his continuing education decided by himself, in the freedom of childhood.

Religion is thus put at the service of art, and the many other distractions, whereas in Plato, as in Catholicism, the task is the other way around.

__________