To whom do you belong? If you are married, to your spouse. If you are a Christian, to Christ. As a creature, to God. We are his sheep, after all, the flock he shepherds. If you were a slave, you would belong to your master.

If you are passionately in love, then you belong to your beloved, in the manner of a slave. Totus tuus was the motto of St. Pope John Paul II, following St. Louis de Montfort: “I am entirely yours, and all that is mine is yours.” And thus someone who loved Mary with such a burning love would, in consequence, be hers.

But do you belong to anyone else? Should you? Should you say that you do?

One might grant that when one person is related to another so as to be “his” such-and-such, then, in a derivative sense, he would belong to that person. For example, if I am someone’s brother, then I am his brother, and in that derivative sense I am “his”, that is, his brother. But there is no end to that sort of belonging. To wit: if I am someone’s plumber, then I am his plumber, and in that derivative sense I am “his,” that is, his plumber. It is some stricter sense we are looking for. In that strict sense, in which someone is as it were entirely someone else’s – it looks as though there are only a few.

And that there should be only a few. “Remember that the heart is a traitor. Keep it locked with seven locks,” wrote St. Josemaría Escrivá. One may interpret this to mean that one should speak in complete confidence to a very few. Unburden your heart only to one or two of your most trusted friends, as the age-old wisdom has it. Surely, along the same lines, you should not say that you are “yours” in the strict sense to anyone besides those just mentioned.

And yet, we do this, commonly, in the valedictions we write in correspondence. We write for example, “Yours sincerely” – which was not much used before 1950. But before that, “Yours affectionately” or “Yours faithfully.” Or commonly one writes, simply, “Yours.” The Oxford English Dictionary attests that “Yours” as a valediction in a letter goes back 500 years.

But isn’t it absurd to say that you belong to someone entirely, because you have written a letter to him?

I have seen it claimed that “Yours” in a valediction was originally rendered “YourS” – with superscript S – which was intended as an abbreviation for “Your servant.” If true, this fact would get around the problem, sort of. Or rather it would kick the can down the road, since why should writing a letter to someone make you his servant? The claim, however, seems to be false. There are no extant letters with an abbreviation like that. And, as I said, “Yours” as a valediction is very old.

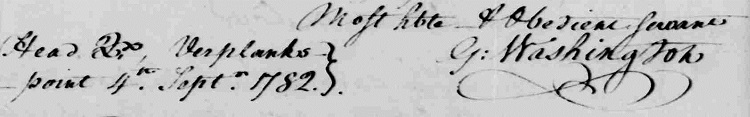

The abbreviations one does find are different. It was once common to end a letter, “Your most humble and your most obedient servant.” That valediction reached a peak in the 18th century and was a favorite, for instance, of George Washington. It represented the height of refinement and politeness and was often abbreviated – as “yr mst hmbl & obt svt” or YMHOS. By 1883, in his book The Art of Correspondence, John Staples Locke could advise that the phrase should be used as a closing only in “official letters.” Indeed, Winston Churchill’s letter of December 8, 1941, to the Japanese ambassador stating that the United Kingdom now considered itself at war with Japan was signed, “I have the honour to be, with high consideration, Sir, Your obedient servant, Winston S. Churchill.” A very polite announcement of war!

But this phrase, “your most humble and obedient servant,” antedates “Yours” as a valediction by several centuries (it was used in Latin) and provides the clue. It is not that “Yours” is an abbreviation for it. It’s rather that someone might say he belonged to another, only because the standard relationship that he regarded himself as having to any chance person was that of a “humble and obedient servant.”

What I am drawing to your attention is how Christendom has worked. Jesus washed his disciples feet in the manner of a lowly servant and taught: “If I then, your Lord and Teacher, have washed your feet, you also ought to wash one another’s feet. For I have given you an example, that you also should do as I have done to you.” (John 13:14-15)

In this spirit Saint Paul taught: “Do nothing from selfishness or conceit, but in humility count others as better than yourselves. Let each of you look not only to his own interests, but also to the interests of others. Have this mind among yourselves, which was in Christ Jesus, who, though he was in the form of God, did not count equality with God a thing to be grasped, but emptied himself, taking the form of a servant, being born in the likeness of men.” (Philippians 2:3-7)

Thus, when you sign a letter, “Yours,” you are summoning this outlook, although you do not know it. You are saying that you belong to this person, to whom you are writing, because you regard yourself as belonging to everyone in the manner of a “most humble and most obedient servant,” on the pattern of the Lord.

It wasn’t a coincidence that the century that prided itself on fully asserting, as if for the first time, the rights and dignity of the human person as free and equal, also held that polite manners bound each of us to address any other person in the way that a servant would address his master. Christianity once taught us that the claim of equality must deteriorate into a destructive assertion of “autonomy,” if we do not freely choose to serve one another in humility. “Yours” and “Yours in Christ” are the same.

__________