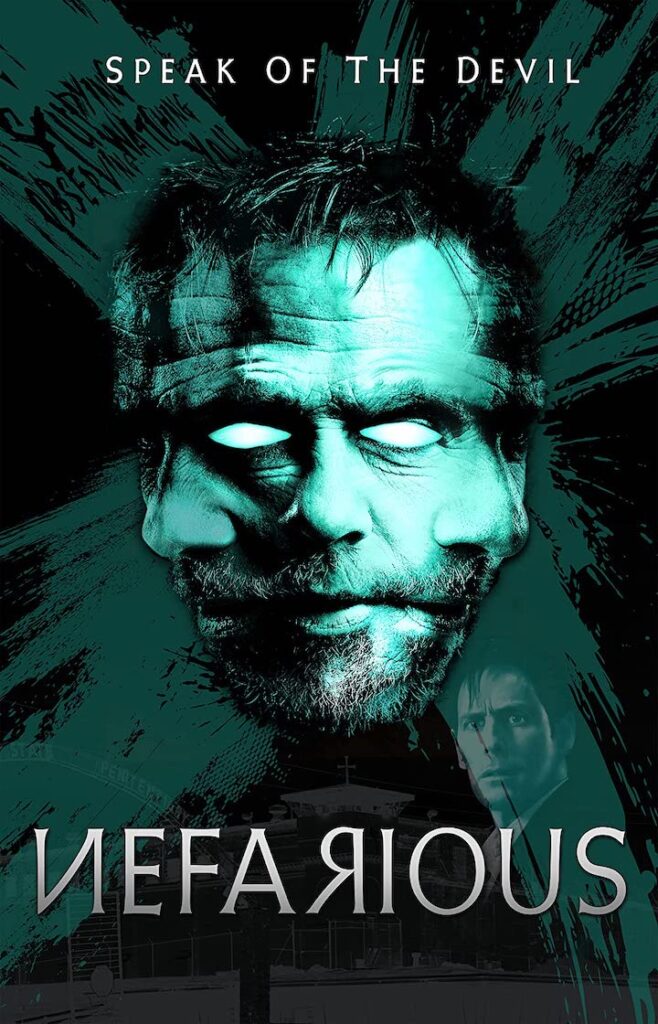

One of the delights – if that’s the right word – of the recent film Nefarious is the bone-headedness of its professional reviewers. One critic described it as Christian and conservative “propaganda.” Another dismissed it as a commercial “for right-wing beliefs” and a “poorly made psychological drama. . .with no real scares and too much over-acting.” On the Rotten Tomatoes website, Nefarious gets a damning 31 percent rating from 16 critics. Right next to it on the same site, the same film gets a 96 percent rating from more than a thousand actual moviegoers.

There’s always a chance, of course, that all those thumbs-up ratings came from End Times evangelicals. But not me; I first heard about it from an Ivy-League-trained Catholic constitutional lawyer. She called it the best film to capture the reality of the demonic since William Friedkin’s The Exorcist (1973). And she’s right. Unlike this year’s other devil film, The Pope’s Exorcist, featuring a dopey script and an overweight Russell Crowe as a priest in urgent need of an Ozempic prescription, Nefarious is deadly serious about the nature of evil. And thus, it’s both convincing and memorable.

The story is simple. On the day of his execution for multiple murders, a prisoner is interviewed by the psychiatrist tasked with determining his sanity. If sane, the prisoner will die. If insane, he can’t be executed. The twist comes early in their conversation. The prisoner claims to be possessed by the demon Nefarious, who wants his host to be executed for purposes that later become clear. The psychiatrist is an atheist, disbelieves in supernatural nonsense, and merely wants to discover whether the prisoner is faking it, or genuinely nuts.

Nefarious is closer to a stage play than a standard movie. There’s not a lot of action on death row. What makes this lean, low-budget film work so well is an intelligent, articulate screenplay and strong performances from both main characters. Sean Patrick Flanery (of Boondock Saints and other films) is astonishing as the condemned man, switching back and forth effortlessly between the terrified human prisoner and the brilliant, sardonic demon who owns him. And Jordan Belfi as Dr. James Martin (note the name; no doubt a coincidence) is the ideal foil.

Nefarious isn’t a perfect film. The closing few minutes don’t measure up to the power that precedes them. But as movies go, it’s hard to dismiss or forget. That’s something few films achieve, and it highlights the anti-religious snark that infects so much of today’s film criticism apparat. The “mortal sin” of Nefarious in a culture of unbelief, the thing that makes it so unwelcome to minds and lives scoured of any faith, is that it shows the devil as intensely personal and uncomfortably real.

And real he surely is. A bishop I interviewed some months ago shared the following experience from the first weeks after his consecration:

The thing that really shook me, when I became a bishop, was a conversation I had with an exorcist, a very good man, and then reading some of his redacted reports. They were deeply sobering. I don’t think people have any idea of how much genuine, satanic evil is out there, the demons that can be present in a person, and the way they can enter a human being through the senses, from the misuse of technology, from generational curses, or through the role of other sins in someone’s history. I know that can sound implausible. Everything is psychology these days. Most people don’t have a grasp of real evil. That’s because we haven’t preached it. And one of the devil’s favorite tactics is to get us to believe that he doesn’t exist. But he’s very real and very active. People who doubt that are putting themselves in serious danger.

Of course, that’s what we’d expect any bishop worth his salt to say. Likewise, the Catholic convert and philosopher of the last century, Raïssa Maritain, described the devil in her small book The Prince of This World as the “author of despair,” “prince forever of illusory independence,” and “the pretender to all empires.” Christian saints and popes throughout the ages have never doubted the existence of a self-aware spiritual being of immense evil, the enemy of God and humanity. But neither, one might argue, did a distinguished, thoroughly mainstream, ex-Marxist philosopher with otherwise ambiguous religious beliefs.

The late Leszek Kolakowski had a lifelong fascination with the nature of evil. He wrote about the devil in history more than once. In his essay, “A Stenographic Report of the Devil’s Metaphysical Press Conference in Warsaw, on the 20th of December 1963,” Kolakowski put the following words into the devil’s mouth in speaking to modern Christian theologians:

You have stopped believing in me. I know all about it, of course. I know all about it, and it is a matter of complete indifference to me. . . .[And yet,] since when does faith tremble before the ridicule of pagans and heretics?. . . .You want to be up to date in this world, to give up “fairy tales,” to stride at the front of humanity. . . .[But] what is it that you must renounce in order to win approbation in this world? The devil?. . . .And do you imagine that this is where the concessions will end?

There comes a moment in Nefarious when the prison’s Catholic chaplain makes a brief appearance. The demon initially recoils in fear. . .until the priest starts blathering about how the Church has “evolved beyond” belief in devils, thanks to enlightened psycho-social tools. Later, along unintentionally similar lines, the unbelieving psychiatrist lists all the human advances in knowledge and behavior that today make religion obsolete. The demon in the human prisoner pauses. Grins. And then says, “I think I love you.”

See the film. Preferably in the daylight. Preferably with a friend.

__________

Nefarious is rated R.