I recently read two hugely different novels in quick succession – The Wings of the Dove by Henry James and The Sun Also Rises by Ernest Hemingway. Published only 24 years apart – the James in 1902, Hemingway in 1926 – they read now like voices from two different epochs (which they were – the epochs being the years before and after World War I, with the war tracing a blood-drenched dividing line between them).

The Wings of the Dove is a subtle analysis of innocence and corruption in posh settings in London and Venice. The Sun Also Rises, narrated in Hemingway’s clipped, tough-guy prose, chronicles lust and violence among self-destructive pleasure seekers in the bull ring and bars – especially the bars – of Pamplona.

Profoundly unalike as they are, however, the books share an intense interest in Catholicism. But since neither author is usually taken for a Catholic writer, that calls for an explanation.

In a 1993 study (The Catholic Side of Henry James), Edwin Sill Fussell traced a persistent fascination with Catholicism running all through the writing of this great “post-Protestant” writer. For example: In probably the best known of James’s stories, The Turn of the Screw, the malevolent ghosts of the dead butler and governess are Catholics; and in James’s last novel, The Golden Bowl, all four principal characters are as well.

And then there is The Wings of the Dove. Fussell cites textual evidence that Milly Theale, the doomed American heiress at the center of the story, is a Catholic. But even more to the point is a crucial incident near the novel’s end.

Trudging around central London on Christmas morning in a funk over his unwitting role in Milly’s death and the moral dilemma this has created for himself and his mistress, Milly’s close friend, the scheming Kate Croy, journalist Merton Densher decides that a bit of religious uplift might help. Seeing he is in the neighborhood of Brompton Oratory, Densher, though not a Catholic, heads there:

At the door then, in a few minutes, his idea was really – as it struck him – consecrated: he was, pushing in, on the edge of a splendid service. . .which glittered and resounded, from distant depths, in the blaze of altar-lights and the swell of organ and choir. It didn’t match his own day, but it was much less of a discord than some other things actual and possible. The Oratory, in short, to make him right, would do.

In the context, making Densher “right” means a great deal more than simply cheering him up. Rather, watching Mass somehow serves to “make him right” by enlightening his troubled conscience to the honorable way of proceeding in his relationship with Kate. It’s in this sense – the possession of real (though unexplained) efficacy in resolving moral perplexity – that, James tells us, exposure to Catholicism in the Brompton Oratory lifts Densher’s troubled spirits.

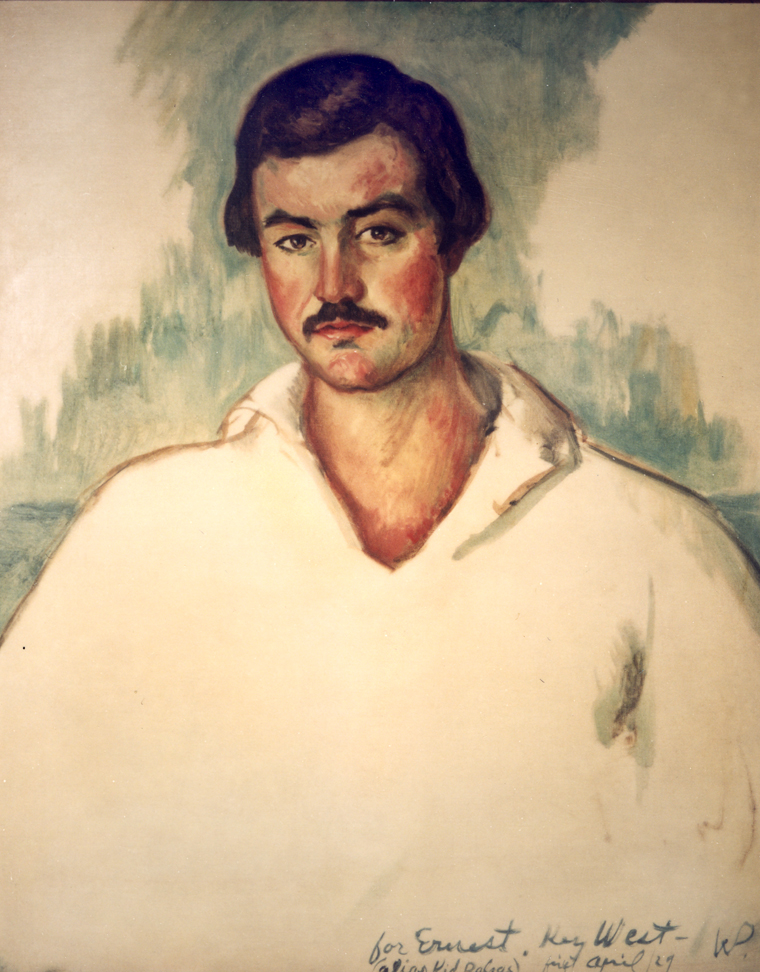

Unlike Henry James, Ernest Hemingway was a Catholic, having converted after being seriously wounded while serving during the recent war as a Red Cross driver on the Italian front.

In a 1927 letter to a priest, he insisted, “I have never wanted to be known as a Catholic writer because I know the importance of setting an example – and I have never set a good example.”

He nevertheless appears to have practiced the faith, until his infidelity to his wife.

Eventually, Hemingway married four times and became a heavy drinker and womanizer. And suffering from depression, for which he received electroshock treatment, committed suicide. Yet however far he strayed from the Church, he seems not to have stopped thinking of himself as a (bad) Catholic.

The Sun Also Rises’s narrator, Hemingway look-alike Jake Barnes, is Catholic. His religious situation – and very likely Hemingway’s – is summed up when Jake impulsively enters the cathedral of Bayonne, in the Basque region of southwestern France, on his way into Spain.

It was dim and dark and the pillars went high up, and there were people praying, and it smelt of incense, and there were some wonderful big windows. I knelt and started to pray and prayed for everybody I thought of, Brett and Mike and Bill and Robert Cohn and myself, and all the bull-fighters. . .and as all the time I was kneeling with my forehead on the wood in front of me, and was thinking of myself as praying, I was a little ashamed, and regretted that I was such a rotten Catholic, but realized there was nothing I could do about it, at least for a while, and maybe never, but that anyway it was a grand religion, and I only wished I felt religious and maybe I would the next time, and then I was out in the hot sun on the steps of the cathedral.

The difference between these two literary visits to Catholic churches is obvious. As if by magic, just being at a rousing celebration of Mass, brings Densher new light on his dilemma, while praying in a dark cathedral reminds Barnes that he is a “rotten” Catholic. But who can say Barnes’ insight isn’t more meaningful than Densher’s?

Fussell suggested that, for Henry James, Catholicism may have been essentially a “literary device.” Perhaps. But the frequency of the Catholic theme in James suggests more. One can imagine him saying grandly: “If there is a personal God and if there is an afterlife – and I prefer to suspend judgment on both – then at least one must recognize that the Catholic Church, with all its faults, is substantially more in touch with God and the afterlife than any other religion.”

Hemingway was a man who became a Catholic, practiced the faith for a time, never formally renounced it, and, suffering from depression, may perhaps have entrusted himself to God’s mercy even while taking his life.

Certainly, we should say a prayer for him now and then – as well as for fastidious, post-Protestant Henry James.

__________