From October 1971 through October 1987 seven assemblies of the Synod of Bishops were held, six “ordinary” assemblies and one “extraordinary,” that reviewed the implementation of the Second Vatican Council 20 years after its close. I was press secretary to the U.S. bishops’ delegations at all seven assemblies and also did a bit of writing for the synod itself. In later years, I covered several synod assemblies as a journalist.

Although none of this makes me an expert on synods, it does give me a certain perspective, grounded in experience, from which to point to problems that threaten to make the upcoming gathering at the Vatican in October a less satisfying exercise in synodality than neither its participants nor Pope Francis might wish.

The first and most obvious problem is size. We are told that the October assembly will have 364 voting delegates, 120 of them appointed in July by the Pope. By contrast, synod assemblies of the past generally made do with 250 or fewer participants – and even that was a lot.

The main question raised by the substantially larger number is obvious. How can 364 people, coming from many different nations and cultures and most of them having no prior acquaintance with one another, hope to reach a meaningful consensus – even a tentative, interim one – on much of anything in only 25 days (bearing in mind, too, that significant chunks of time will necessarily be devoted to liturgies and ceremonial events)?

The honest answer, of course, is that they can’t. And that points to a second big problem. The synod managers – assuming they’re acting in all good faith – will presumably feel obliged to cobble something together on the basis of notes taken during the discussions and their own preconceptions.

With time running out, the work product will be presented to the weary participants at a moment when many will be looking for something – anything – to point to as the fruit of the first stage of the Synod on Synodality. Unfortunately, however, the whole procedure will also contribute to already existing suspicions of manipulation.

And recall, by the way, that a second, and presumably definitive, synod assembly is already scheduled for October of 2024. If it’s as large and unwieldy as the first stage is shaping up to be, it’s hard to see how it can escape the same unhappy, inconclusive fate as its predecessor.

The third problem is secrecy – or, more properly perhaps, a demoralizing absence of transparency. In preparing for synods of the past, the U.S. bishops’ conference elected its delegates during open sessions of its general meetings with the press present. The Vatican didn’t like that, but the bishops persisted.

During the synod sessions, moreover, the Americans held regular news conferences and gave individual interviews. The Vatican didn’t like that either, since it preferred to limit the information flow to its own press briefings. But here, too, the Americans persisted, and no one was any the worse for it. In fact, the overall credibility of the synod probably was enhanced.

This time, apparently sticking to Vatican rules, the U.S. bishops chose their delegates in secret session, and the names were only announced by the Vatican later when it announced the other participants. As to information during the October meeting, it remains to be seen how the Vatican will handle that, but the preference for secrecy and centralized control up to now does not inspire much confidence that this will be an open, transparent gathering.

According to the working document for the synod, the pre-assembly consultations turned up several more or less sensitive topics for discussion including married priests, women deacons, and outreach to LGBTQ+ persons. In that context, it’s notable that besides the five Americans chosen by their fellow bishops as delegates, the Holy Father named another five who are commonly considered particularly sympathetic to his views.

The pope certainly has that right, but there is a certain tension here with the image of synodal conversation as a process without a predetermined result where everyone can speak his or her mind.

Finally, let me offer a personal observation about this ecclesial exercise.

We have heard repeatedly that the desired result of the whole process is a synodal Church equipped for evangelizing outreach to the peripheries. Very good. But what is to be the message to the peripheries: “Come join us in a giant consultation process that we call ‘Church’”? Frankly, I hope not.

Looking for a better answer, I turned to Pope Saint John Paul II’s powerful 1998 encyclical Fides et Ratio (Faith and Reason). And there I found some questions that John Paul says people have always asked themselves: Who am I? Where have I come from and where am I going? What comes after this life? Why is there evil?

These may indeed be perennial questions, but there are plenty of reasons to think that today many people – including many on the peripheries – aren’t asking them. The siren song of a secularized culture instead distracts them with constant images, sounds, and consumerist appeals that move them to obsess on other questions: How can I get? How can I keep? How can I enjoy? What can I want that I don’t even know about yet?

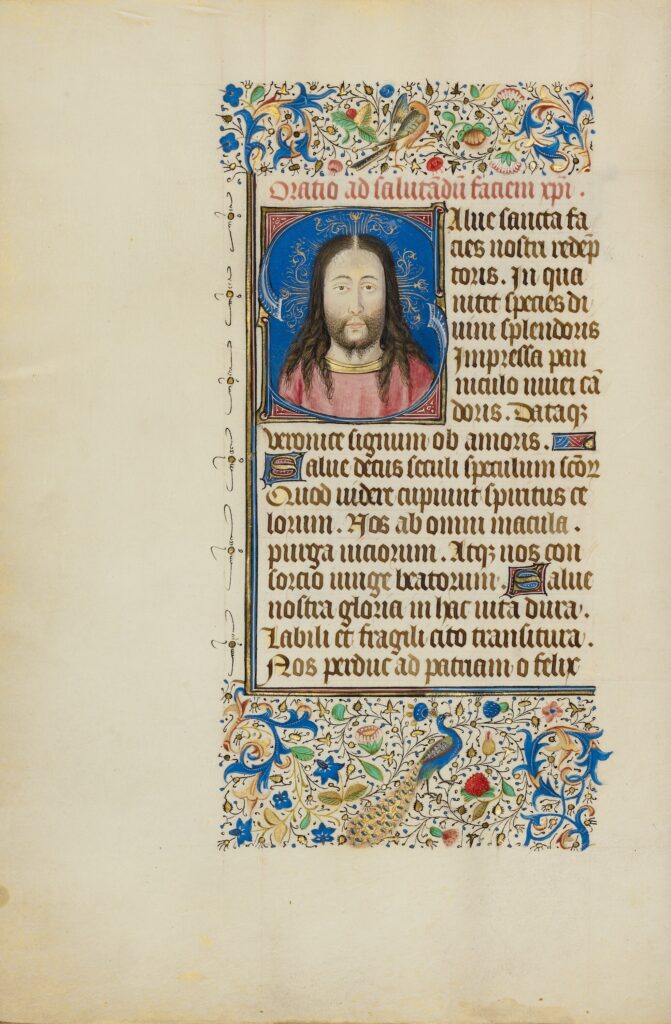

If what I’ve just said is correct, it follows that the synodal Church must acknowledge those questions about getting, keeping, enjoying, and learning to want, and take them as starting points for raising the perennial questions. In other words, far more than the usual hot-button issues, it will have to address – and urgently – evangelization, how to tell people with loving conviction that, today as always, the answers have a human name and a human face: Jesus Christ.

__________