Two thousand years ago God walked around Judea and told a parable about a despised Samaritan who assists “a man” – it could be any man – who was attacked by robbers, stripped of his clothes, and beaten nearly to death. St. Luke, perhaps hearing the parable from Mary herself, did us the great favor of writing it down.

About eighty years ago the mother and father of a large Catholic family in a small farming village in Poland were reading that same parable. They underlined its titled, “The Good Samaritan.” They underlined the verses: “But a Samaritan, as he journeyed, came to where he was; and when he saw him, he had compassion, and went to him and bound up his wounds, pouring on oil and wine; then he set him on his own beast and brought him to an inn, and took care of him,” (10:33-34). And then they wrote in pencil in the margin, “Yes.”

And this, my friends, is how Christianity works.

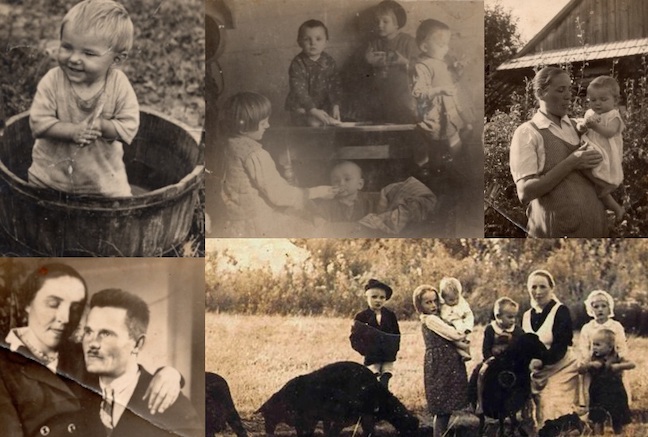

This mother and father were Jozéf and Wiktoria Ulma. Presumably they wrote “Yes” when, in the summer of 1942, they resolved, along with their six children, that they would hide Jewish families on their farm, to protect them from the Nazis.

They took in as many as their farm could accommodate: according the Yad Vashem, the entire Szall family (father, mother, four sons), and the two daughters of Chaim Goldman. They undertook this risk as a family since, as they knew, if they were caught, all of them would be sent to a death camp.

For two years they succeeded. But after they were denounced (perhaps by a fellow Pole), German police descended upon the farm, in the pre-dawn hours on the morning of March 24, 1944, and shot the Jewish families. Then, after conscripting witnesses, they shot Jozéf and Wiktoria in front of their children. And then they shot the children, “so that they wouldn’t be of trouble to anyone,” a German police officer said after the fact.

“During the shooting one could hear terrible cries and lamentations. The children called their parents, and they had already been killed,” one witness said. A man who shot some of the children remarked, “’Look how the Polish pigs that have hidden the Jews are dying.”

Wiktoria was expecting and near term. She either went into labor during the executions, or her body delivered the baby after birth (a so-called “coffin birth”), because when her remains were exhumed, it was discovered that her child was partially born, its head and torso appearing from the birth canal. According to the Postulator, Fr. Witold Burda, the remains were too decomposed to discover the sex of the baby.

The Ulma family was beatified on 10 September in their village of Markowa. Their feast day is Jozéf and Wiktoria’s wedding anniversary, July 7th.

Some observations.

• They were a large family, with seven children. Jozéf married Wiktoria in 1935, when he was 35 and she 23. They had six children before she turned 30. One must posit a direct connection between (a) their death to self and openness to life, shown in their generous acceptance of children, and (b) their heroic actions during the war. Stunningly, they conceived their seventh child in the darkest days of the Nazi occupation, and while they were sheltering Jews at peril to themselves. That baby was a witness to their love. “The baby was trying to come into the world,” Fr. Burda remarked.

• Their martyrdom was on the vigil of the Annunciation, as St. Maximilian Kolbe’s was on the vigil of the Assumption, a “kiss” from their Mother.

• Some want to know – is this seventh child, also Blessed, an unborn child? By this they mean, did he die while not yet born and is counted a martyr? It seems likely that this is so and that he was delivered stillborn, especially if Wiktoria was only in her seventh month, as some sources report.

• The name of this child was presumably not known even to the parents. Wiktoria was close enough to term that they would have picked out a name for a son and a name for a daughter, but in those days, they would not have known which. Indeed, now they do know. Through death their child received a name, which they know and we do not – as if that child remains “safeguarded and sheltered” by them in their marital love.

• Wiktoria was a homemaker and Jozéf a farmer. They worked very hard on building up the ‘substance’ of their family, saving to purchase a larger farm, and improving the lands and buildings constantly – no “greed” in such industriousness. Jozéf especially was very involved in the “civil society” of his town, as a librarian, devoted photographer (then still a new technology), and active member of the Catholic Youth Association. Their love of Life was a love also of being alive. As Fr. Burda put it: “They were not looking for some other reality, not running away from the world, but instead immersed in it. Through such a way of life, they all the more discovered the beauty and depth of their everyday life.” It was because they wanted to live that they risked death. They were not morose, escapist, or implicitly suicidal: “They very much wanted to live. . .constantly discovering the Lord God, the beauty of everyday life, the beauty of life.”

Another teaching of the Lord to which they said “Yes”: “Whoever loses their life for my sake will find it,” (Mt. 10:39).

Heroes who have received the Congressional Medal of Honor (not posthumously) will typically say, “I did only what anyone else would do,” and “Many others did the same who will never be known.” Canonized saints and the blessed are just like this.

Let us, like the Ulmas, in the presence of “the Father who sees in secret,” find a verse in the Gospel to live by and structure our lives around a “yes.”

__________